Short Fiction

Finalist: When Dr Z Retires

When Dr Z turned 69 he decided he had had enough listening to everybody else’s trouble. Enough sitting on his bum.

The bum, after all, was hard to avoid. If he rode his bike, it was still there under him. And playing the piano or guitar, the same thing. And worst of all, writing. You sat on your bum the longest, maybe all morning and all afternoon and sometimes all through the night. You got up and walked around only to come back again. You would be thinking, your ankles are beginning to swell, your back is stiffening, your eyes are bleary from staring at the screen. You would get up for a glass of water, bend over like an old person, rub your eyes and stretch only to come back.

Well, Dr Z, you are an old person. That’s what retirement is about. You are going to do something new.

Don’t bother me with your existential worries, your wife says in your head. Go for a bike ride and put your bottom to good use.

Dr Z knows she didn’t exactly say this, not in this way, not at precisely this moment. First of all, she wouldn’t talk like that. And second of all, she was much nicer than he is letting on. He just thought of her and the bike, because that’s where he was going at that moment, into the garage to pump the tires. She probably said something more civilized, like, Why don’t you enjoy yourself and, you know, ride your bike and take it easy. Shake those stories out of your head. You have too many stories in there and they don’t all belong to you. It’s time to get a little lighter.

Basically he has two wives: the real one, and the one in his head.

The real one is kind and supportive. The other one, the one of his own creation, is different.

He goes for a ride. The bike creaks, the derailer is stuck and the chain won’t leave the small sprocket. He puts on his fast boots, the sleek red and black ones with the BOA. He pumps the tires, plugs in the light. He gets going fixing up his bike, and fixes up everything he can, as if there is going to be a test and he doesn’t want to compromise his score. He degreases the chain and oils it for good measure, and the derailer clicks in, responds, moves the chain back and forth. He plans his route: distance, time, speed, calories, watts. He zips by the golf course, the beach, the woods. He is old, his speed has diminished. He is spending too much time watching himself go slow.

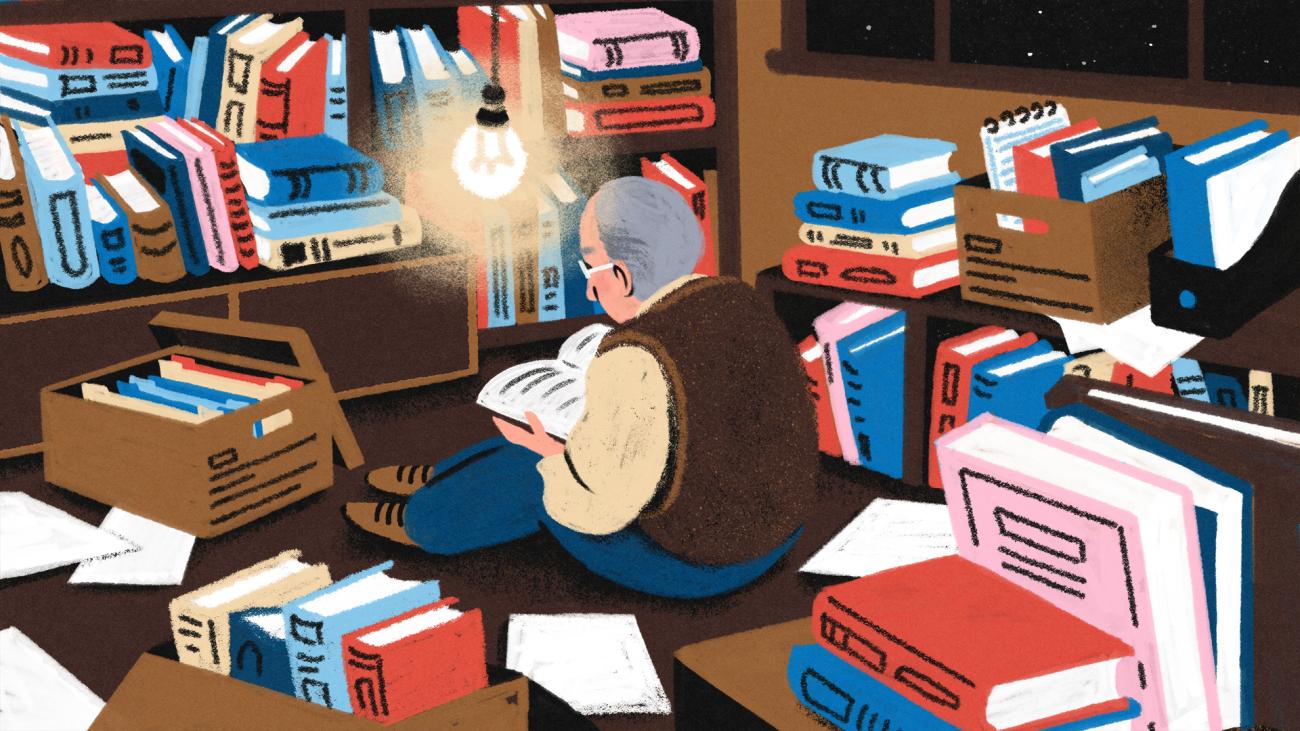

Three months later he is in the office, sitting cross-legged on the floor surrounded by books, piles and piles of books. The piles are labelled in his mind: Therapy, Pharmacology, Plasticity. He has a pile for Fiction (huge and overflowing and not belonging there in the first place), and a pile that he calls Antipsychiatry, saved from his university days. Essays, Ethology and Evolution, of course. And Neurology. The books are piled up and up, ready to tip over, but he doesn’t think about how he can get them up and out.

Carina says, Go make some sense of all those books. You can’t leave them here. Time to clean up and have some fun.

And the Carina in his head says, I’ve known you forever, and it’s time for you to get off your ass if you want to retire. You have too many books and they are too heavy to lug around, whether they are in your head or on the shelves. Don’t make me throw them in the recycle bin for you. My shoulder isn’t up to it. And it’s your job, anyway, not mine. The Carina in his head won’t shut up.

The real Carina is considerate to a fault. She is nothing but considerate and has put up with him graciously all these years.

The Carina in his head has no manners, goes red in the face at the slightest provocation and won’t take no for an answer. Neither of the Carinas is ever likely to read any of those books.

There is a tall slender man in the street who walks back and forth with his basset puppy, looking a little lost. He was in Dr Z’s UBC medical school class and is exactly one year older than him. Dr Z doesn’t know what to say when he sees him passing by in the street. It is obvious that the man, Eddie, doesn’t exactly recognize him, but the trouble is, Eddie doesn’t exactly not recognize him either.

Eddie has a look on his face that suggests he has been here before. He is supposed to know what is going on. He is going to make a mistake and be punished for it. Like many people with their pets, Eddie looks like his dog. He and the dog are connected, a print run of two.

When Eddie walks by, Dr Z comments on the dog. He doesn’t say, "Hi, Eddie," or "How are you, Eddie," or "Nice to see you in the neighbourhood after all these years, Eddie." He says, "I love your dog," and "That’s a lovely dog," but stops short of saying anything else.

Dr Z doesn’t want to upset Eddie. He doesn’t want to mention retirement. He doesn’t want to remind Eddie of medical school, remote friendships or connections long-forgotten. Dr Z has a hard time looking at Eddie in the eye because he and Eddie had one of those conversations 40 years ago outside the anatomy amphitheatre, the kind of conversation nobody ever forgets.

Eddie was lumbering in his bear-like way and smiling his old healthy smile and talking in his booming voice about the homework project. The project was the body, any part of it. Choose the part you care about, Dr. Freidman said casually. Choose the organ you love and write an essay linking form and function. Right, form and function. The youthful Dr Z agonized about the project and eventually talked with Eddie to try to get going on it. Eddie told him straight up, Why don’t you look in the books to get ideas, so that’s what he did. Eddie knew that’s what Dr Z would normally do and was making fun of him.

The youthful Dr Z forged on and made up something about the adrenal gland. The adrenals were small, formless, inconsequential. They appealed to him because they were almost invisible, slipping off the top of something more important (the kidney twins), slinking away back there, out of view. They were almost invisible but you still couldn’t live without them, he hoped, although he couldn’t exactly explain how or why. Most of the class chose the heart, he noted belatedly. He was chastened, too embarrassed to copy them.

Eddie knocked him on the shoulder and said, It’s obvious. Form and function. It’s the penis. Plain and simple. One word: penis. For the penis, form was function, and Eddie didn’t have to explain a thing. Eddie got an A, and Dr Z squeaked by with a terse comment and a grudging pass, wondering what he was doing in medical school in the first place. He was convinced his adrenal project earned him a big question mark beside his name way back where he belonged, at the end of the alphabet.

Dr Z doesn’t want to mention the remote conversation between the penis and the adrenal gland. Eddie will not know what he is talking about. He will not know what to say, he will not remember, and there will not be a laugh of recognition. So Dr Z asks again about the dog, and Eddie says that the dog is from Al…Albrrr-, you know, the next province over. Eddie turns his head to the right, towards the sea, and Dr Z thinks, Good for you, Eddie, good guess, all of the next provinces are over there across the water of the bay.

But Eddie looks like he thinks he made a mistake. His face is scrunched up and almost wizened, Eddie who used to be big. Eddie smiles oddly but finds the lost word, "Alberta." The doppelganger dog is from Alberta. He smiles, says "Alberta" again, with more confidence. He is enjoying repeating himself.

The Eddie in Dr Z’s head doesn’t say anything at all.

In early winter the king tide rose and threatened to breach the dyke. There were three-foot breakers and angry whitecaps. The current was pushing everything it could find northwest up the bay and along the sandbank. Countless branches, even severed trunks, pooled against the concrete stanchions. Plastic chairs left out for summer wanderers had already disappeared in the surf. Decorative buoys tacked to fences on Seaview Drive swayed back and forth, harshly knocking wood. The wind jumped off the waves and skirted around the houses like frenzied cats, scattering empty cans, clotted leaves, bits of plastic.

All morning SUV’s and pickup trucks pulled past the sandbags to the dyke and sat there watching the water rise, facing east across the bay. That’s when the F-150 ran over Eddie’s foot. Dr Z didn’t see what happened. He was a block away, his eyes half shut, his face to the wind, tugging his chubby black lab, angled blindly forward. He was careful to let the trucks past. They nudged along his left shoulder and turned north carefully, slowing down to a crawl while the drivers gazed out over the frothing bay.

Eddie was up ahead, tilted to the side. The black truck seemed to glide by him, gliding on the water, and Eddie sat down. Just like that, he sat down. Dr Z couldn’t see that Eddie was smiling when the pup crossed over in front of the truck. The basset had crossed into the ditch and was sniffing the bushes, dragging the leash that was quickly wrapping itself up in the rear left tire.

Metatarsal, that’s what was broken.

Eddie heard the crack. Felt the point of something sharp inside his foot.

Meta tarsal. It was two words, and it was the right answer.

He said it loud enough that he could hear himself above the howl of the wind.

He had seen what was happening, what was going to happen, so he let the leash go and sat down on his bum, right in the middle of the road.

The alumni UBC Short Fiction Contest

This year marked alumni UBC’s first short fiction contest for alumni. "When Dr Z Retires" was chosen as one of three finalists from almost 100 entries. Many thanks to UBC’s School of Creative Writing and UBC Okanagan’s Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies for their support of our inaugural short fiction contest.

The jurors, all UBC alumni, were Annabel Lyon (author, director of UBC’s School of Creative Writing), Michael V. Smith (author, professor of creative writing), Danny Ramadan (Syrian-Canadian author), and Umar Turaki (writer and lecturer at UBC Okanagan’s Faculty of Creative and Critical Studies).