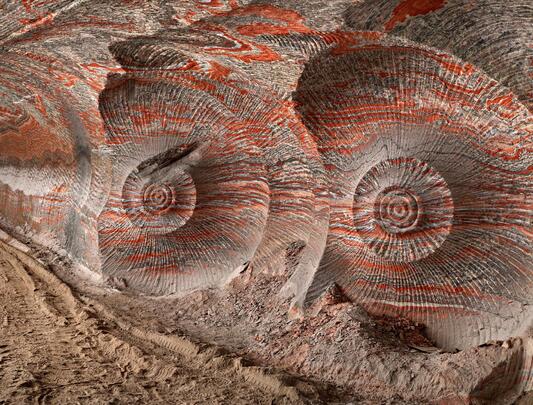

Uralkali Potash Mine #4, Berezniki, Russia, 2017. Photography by Edward Burtynsky.

Clean energy’s catch‑22

Critical minerals are the backbone of clean energy technologies, but finding them is hard, and mining them can be a dirty and often unethical business. A UBC initiative is taking on the challenges.

An annoying feature of closed systems is that the solution to any problem is likely to generate a new problem – sometimes not as bad, sometimes worse, but often equally intractable. Just as there is a law of conservation of energy – in which energy, even if transformed, is always conserved over time – there appears to be another law: the conservation of trouble.

Such is the case with the challenge of switching to renewable energy from the climate change scourge of fossil fuels. It’s not easy to capture wind, hydro, or solar power and pour them into the tank of your car, but the feedstock is free. Even counting the cost of infrastructure, an improbably enthusiastic report in The New York Times recently proclaimed that the price of solar installations is falling so quickly that, by 2030, “solar power will be absolutely and reliably free during the sunny parts of the day for much of the year.”

But, as Department of Earth, Oceans and Atmospheric Sciences (EOAS) head Dr. Philippe Tortell noticed when he began considering this issue, there’s a catch. “All of those new renewable energy sources required a fundamentally non‑renewable resource; minerals and metals needed for batteries, circuit boards, wiring, and other components of the digital, carbon‑neutral economy.”

This is no small problem. Humankind’s appetite for metals and minerals is voracious and, as with fossil fuels, the easy sources have largely been tapped. Take copper for example: EOAS professor of geological engineering Erik Eberhardt reports that global copper production rose from half a million tonnes a year in 1900 to 25 million tonnes today, and demand is expected to double by 2035. Given a paucity of new sources under development – and the fact that new mines often take 10 to 15 years to get through consultation, planning, permitting, financing, and construction – we’re facing a copper shortage (a supply gap) expected to hit 10 million tonnes a year by 2030. On top of this, the demand for other critical minerals such as lithium, graphite, cobalt, nickel, and Rare Earth Elements (REEs) could increase 10‑ to 40‑fold.

Raw supply, however, is not even the most difficult problem. Beyond mining’s scientific or technical challenges, Tortell notes the complicated tangle of environmental, legal, economic, social, and political issues, as well as the question of the historically abrogated Indigenous rights and title.

Perversely, as we’re accelerating our search for minerals to reduce the environmental threat of climate change, mining itself is often environmentally catastrophic. In their dominant form, massive modern mines can devastate the landscape and leave large, even more dangerous scars. Think about the Mount Polley mine in central BC, which in 2014 spilled an estimated 25 million cubic meters of toxic tailings into nearby lakes and creeks – a calamity for local drinking water and spawning salmon. Consider the 2019 breach in the Brumadinho mine’s tailings pond in Brazil, which inundated a local community and killed 270 people. Or the collapsing heap at the Faro mine in Yukon, which closed in 1998, but left behind 70 million tonnes of toxic tailings, 320 million tonnes of waste rock, and an unclaimed clean‑up bill of more than $2 billion.

Dr. Roger Beckie, a hydrologist, engineer, and a professor in EAOS, has written that the mine tailings generated worldwide since the eighteenth century would cover the state of Connecticut 10 metres deep, while waste rock would add 10 times that amount. Mining, Beckie says, is primarily a waste management business. And we’re not managing well. Dr. Allison Macfarlane, director of the UBC School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, points out that, after generations of trying, there isn’t a single safe repository for high‑level nuclear waste operating anywhere in the world.

Mining is also a curse on water. Dr. Nadja Kunz, Canada Research Chair in Mine Water Management and Stewardship, says, “No matter where you are in the world, there is always a water problem,” often tied to resource extraction. Mining, Kunz says, withdraws six to eight trillion litres of water a year, enough to sustain 12 per cent of the world’s population. And clean‑energy ores are exacerbating the problem. It takes 1.9 million liters of water to produce each tonne of lithium – a particular problem when the largest known lithium deposit is in Chile’s Atacama Desert, the driest place on earth.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, mining is also a geopolitical booby trap. Dr. Carol Liao, associate professor at the Peter A. Allard School of Law and the Distinguished Fellow at the Peter P. Dhillon Centre for Business Ethics, UBC Sauder School of Business, points out that China has been “buying up mines like properties in a game of Monopoly” and now controls about 60 per cent of worldwide critical mineral production, as well as 85 per cent of the Processing capacity. So, even resource‑rich jurisdictions like Canada are beholden to China to refine ore into the minerals and metals we need. Liao says, “Some are calling the future of critical minerals ‘the New Cold War’.”

Clearly – and fortunately – Tortell is not alone in his concern about these issues. Canada is home to more than 75 per cent of the world’s mining and mineral resource companies, and UBC has long been the intellectual and research backbone of that mining community. Looking around UBC in early 2022, Tortell found a variety of mining‑related research that was “inspired and impressive.” But, he says, “Much of it was running on parallel tracks, with relatively little cross‑fertilization between academic silos.” So, he convened a “Future Minerals Working Group,” a diverse collection of experts, including everything from engineers and geologists to economists, lawyers, and policy specialists, mostly from UBC, but including Indigenous and industry leaders, and academic and creative contacts from around the world. And he challenged them – with no promise of funding or publishing options – to start brainstorming solutions that would work across their myriad disciplines, to forge a better understanding of the issues, to call public attention to the implications and, perhaps, to push the mining and policy worlds in a more sustainable direction. Or, as Tortell puts it, to “make an impact that was a little more transcendent.”

The first challenge, common in interdisciplinary settings, was learning to speak to one another. Dr. Werner Antweiler, an associate professor in the Sauder School of Business, joined the group to find that, “We were all speaking different languages and relying on different ways of approaching the subject matter.” Tortell also noted the effort needed for specialists to understand other people’s work and to shuck off disciplinary jargon and explain their own subject areas. But Antweiler reports that the work paid off: “I really enjoyed having these different voices. It taught me a lot.”

The second challenge – and a high priority – was finding a way to communicate more broadly. For the major outreach exercise, 35 contributors, including a range of academics and Indigenous elders, as well as eight composers and a photographer, collaborated on a book, a musical suite, and a photo collection. Published this year, the book is Heavy Metal: Earth’s Minerals and the Future of Sustainable Societies, and is freely available to read online via Open Book Publishers. As editor, Tortell says the contributors sought “to make complex ideas both accessible and engaging.” Indeed, the collection is readable, informative, charming in its vision and hopefulness, but often unsettling.

As photographer Edward Burtynsky writes, introducing his beautiful, sometimes devastating images of the disruption that mining has caused, “The problem is that we have expanded well beyond the limits of what the planet can sustain, and we’re waking up to that fact a bit late in the game.”

You could sort the academic contributors to Heavy Metal (including all those quoted above) into three groups – Doers, Dreamers, and Worriers – although the categories frequently overlap. The Doers are led by Dr. Shaun Barker, associate professor and director of the EOAS Mineral Deposit Research Unit, whose matter‑of‑fact chapter, “Where We Find Metals,” describes how and why large mineral deposits form on Earth; it’s a guide to where to look. But Doing turns quickly to Dreaming as other specialists look to ore bodies in more complicated locales. Dr. John Wiltshire, an emeritus professor at the University of Hawaii, describes mining on the sea floor, where manganese nodules “simply sit on the seabed waiting to be harvested; there is no tunneling, blasting or digging – simply collecting.” Of course, the law of the conservation of trouble applies. “The heavy machinery used to collect manganese nodules moves across the seabed like a steamroller, destroying all non‑motile organisms in its path.” Perhaps a dream and a nightmare.

Even farther afield, Dr. Sara Russell, a researcher in planetary sciences at the Natural History Museum in London, and Riz Mokal, a former chair of Law and Legal Theory at University College London, write about “Mines in the Sky,” noting that while there are only about eight million tonnes of cobalt on earth, “a single metal asteroid with a mass of around three billion metric tons could supply thirty million (tonnes).” Of course, mining in space remains a distant dream, but Russell and Mokal note that prognosticators from Texas Senator Ted Cruise to astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson “agree that the first trillionaire will be an entrepreneur in the asteroid mining sector.” And Elon Musk and company are doing more than sniffing around.

There are other chapters on exploration and recovery, speculating on mining under the melting ice in Greenland or Antarctica, and on the potential of mining at a small scale. Mining engineers Dr. Marcello Veiga from UBC, and Dr. Alejandro Delgado‑Jimenez from the Colorado School of Mines, point out that the medium‑to‑large companies that dominate global mining employ four million people and claim annual revenues of US $3 trillion. But artisanal mining – informal, easier to start and stop, and often with a much lighter environmental footprint – employs 45 million, pointing to one promising area where we could pick up the pace of innovation and implementation. Small‑scale, often unregulated mining, however, also includes a distressing number of desperate people, including children, facing a whole different set of risks. Yet more trouble.

As Tortell envisioned, these complex issues require not just technical innovation, but real creativity. Which, he says, inspired the working group to commission eight international composers to collaborate on a Heavy Metal Suite, “to help people to be more expansive in their thinking.” Notwithstanding the “heavy metal” reference, the suite, which can be heard in a recording of the Chicago‑based quintet Axiom Brass in an April 22, 2024, CBC Ideas episode, is more classical and considered. Less rage, more yearning.

Now, having done his part as “a convenor of talent,” Tortell is passing the torch, first to Kunz and to Sara Ghebremusse, the Cassels Chair in Mining Law and Finance at the Western University Faculty of Law. (Ghebremusse’s dreamy chapter contemplates an “Afrofuturist vision,” using the fantastical Marvel world of Wakanda as a model for how mining might be managed within the mandate of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). Kunz and Ghebremusse are co‑principal investigators in a New Frontiers in Research Fund study tapping expertise and methods in earth sciences, engineering, law, economics, and public policy, to reimagine the technical, social, environmental, and human rights dimensions of mining in the context of resurgent Indigenous sovereignty.

In which regard, the last word goes to the lead authors in Heavy Metal, Allen Edzerza, an Elder of the Tahltan Nation, and Dave Porter, an Elder of the Kaska Nation and CEO of the BC First Nations Energy and Mining Council. Their opening essay is a thoughtful, bruising look at the history and continuing injustices of colonialism and mining, concluding:

“Together, we can (and must) transform the global mining industry, through new technologies and methods, but also through a fundamental culture shift towards collaboration and mutual respect between Indigenous and non‑Indigenous people. As we seek to address the existential threat of climate change, we must consider what we will leave behind for future generations. Yes, we must supply critical minerals for renewable energy, but we must also protect our lands, waters, air and wildlife. It is a sacred responsibility that the Creator has placed upon us. The Elders tell us that the Creator is speaking to us. We must stop and listen.”

Photos © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Paul Kuhn Gallery, Calgary / Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto