Illustrations By Nathalie Lees

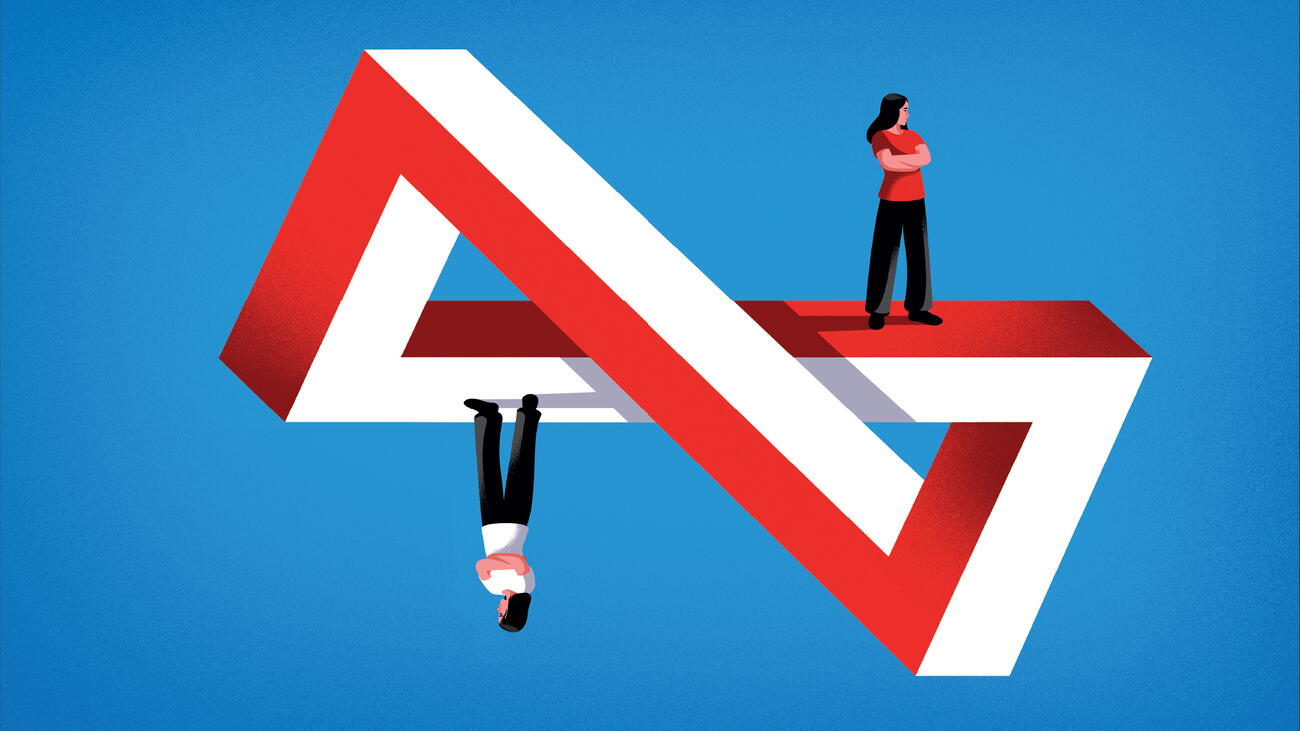

How polarized are we really?

Even the most hostile political adversaries may have more in common than they think.

This is where the culture wars have landed us: two tribes, ideological opponents glaring at each other across the figurative aisle, interminably separate and boiling with rage. This, many are concluding, is no way to live. And it’s a dangerous way to organize ourselves politically – for at the end of this road lies chaos, autocracy, or both. But there may be a silver lining in the story of our polarization, as the work of UBC researchers reveals.

It was not a foregone conclusion that it would come to this. Five years ago, in a much-cited paper, UBC psychologist Kristin Laurin and her graduate student Gordon Heltzel (MA’19, PhD’24) proposed that there were two ways the US political landscape could change: it could become more polarized, or less. More because polarization is a self-reinforcing cycle, or less because extreme polarization makes us unhappy – social creatures that we are – and we’re inclined to self-correct. We now know fate favoured Door Number One. (That’s due to a number of factors, including the impact of COVID and a second round of Trump.)

And so here we sit, each in our silo, drawing a heavy red line between People Like Us and People Like Y’All. South of the border, folks are literally moving out of state to be away from their ideological foes and with their own kind. Which is a huge red flag, for there’s ample proof that extreme polarization undermines democracy.

And yet, in a way, the news is not as bad as it seems. The sense that progressives and conservatives are “two solitudes” with irreconcilably different ways of thinking is a bit of an illusion. In short, we’re not as polarized as we think we are.

In a recent study, Laurin compared the qualities that people said they liked in their allies with the qualities they rewarded online by liking or sharing content. The two didn’t add up. People claimed to prefer a nuanced, generous communicational mode, but their online behaviour suggested it was the guns-a-blazing, we’re-the-good-guys-and-you-bastards-are-out-to-lunch tweets of the hardliners that got the love.

Somehow, a disconnect happens between our mind and our retweet finger. The question is why.

“I used to think people are just lying when they say they respect moderation, and we should believe their actions and not their words,” says Laurin. “But I’ve come to a different understanding. I don’t think it’s the same people whose words are contradicting their actions. I think most people’s actual values are invisible under these powerful social forces” – in this case the small minority of extremely opinionated people who shape the norms on social media. And then those damn enmity algorithms whip up the polarization even further.

Social media is a reality-distortion machine. “We buy into these crazy stereotypes about what our opponents actually believe,” Laurin says. “I have a colleague who studies what people’s own beliefs are and then compares them to their opponents’ beliefs. And there is so much overlap. But we perceive each other to be these cartoonish exaggerations.”

All this is good to know. Because understanding what’s clouding our judgment might set us on track to behave in ways that are more aligned with who we are, rather than who we think we’re supposed to be.

Over in UBC’s political science department, Dr. Maxwell Cameron (BA’84) investigates polarization in a different context. One of his passions is preparing people for public life by training them to achieve common goals “within a framework that is highly adversarial” – the parliamentary system.

Maxwell co-founded the university’s Institute for Future Legislators (IFL), a program in which aspiring politicians role-played the cut-and-thrust of actual parliamentary debate. In its way, the parliamentary system is every bit as polarizing as the Internet. It amplifies the differences between out-group and in-group.

“Two things promote partisanship in politics,” Cameron says. “One is elections, which are competitive – you join a team and immediately you become partisan. And then there’s just the environment of the legislature. You’re sitting on opposite sides of the aisle – two sword-lengths apart. You get angry at the other side; you want to prevent them from getting in your way and doing things.”

Humans are tribal by nature – blame our evolutionary wiring. The moment we join a group, “team spirit kicks in very quickly,” Cameron says, and we start thinking in terms of Us and Them.

Cameron observed this in IFL time and time again. “One year, shortly after people were randomly assigned to parties, one of the participants fell ill. We had to call an ambulance and they took him to Emergency. He ended up being fine. For a while, though, everyone was concerned. But the only people who called or visited him in the hospital were the members of his own political party! They felt a duty to him that people in the other political parties just didn’t feel, even though the parties had just been formed.”

If our behaviours are super-malleable – and they are – the good news is it can work both ways. Just as we learn bellicose partisanship, we can learn the opposite: to mitigate the expression of our primal instincts, the better to arrive at a place where constructive engagement can happen.

This is the secret sauce of the role-playing element of Cameron’s IFL. Experiential simulation is powerful. It’s especially useful for acquiring practical skills. The whole enterprise of conducting “the people’s business” is one for which folks are woefully untrained. “The most consequential decisions in a society are made by amateurs,” Cameron says. “By which I mean, most politicians had very little experience before they ran for office. The practice of politics, unlike political science, is rarely taught.” To learn any skill – to turn theory into practice – you’ve got to get your reps in – hence the IFL’s weekend boot camps, followed by a parliamentary simulation held in the chambers of the provincial legislature.

But just modelling a toxic system isn’t helpful. Cameron found that if students simply aped the adversarial Westminster model of parliament – with its incentives to blind party loyalty and weak co-operation across party lines – you got a garbage-in-garbage-out effect: they never progressed beyond the incentives to unhealthy polarization.

That’s why a debrief layer is so important.

“Here we borrowed the model from the UBC medical school, where students transitioning from classroom curricula to clinical practice learn ‘reflective competencies’ through group discussions. What we call ‘reflective circles’ enhance students’ acquisition of practical skills from one another and from mentors.”

That post-game reflection helped the participants shake off any inclination to extreme polarization. “They gained detachment from their parties, even as their appreciation grew for the complex balancing acts that partisan politicians must continuously perform,” Cameron says.

There’s a “walk a mile in my shoes” element to this kind of role-playing. It’s hard to remain enemies with people you have truly made an effort to see and hear.

In the social sciences, there’s a phrase that captures how to shrink the distance between two people who are at loggerheads – emotionally and maybe even ideologically: “Contact weakens polarity.” Actually sitting down and talking with someone who you thought was your enemy invariably makes you come away feeling less judgmental. Many interventions have proven useful in this respect – from deep listening, to curiosity, to cultivating intellectual humility by making understanding your primary aim.

“Anything that gets you to acknowledge the other side’s humanity really can work,” Laurin says. But there’s some evidence that the most powerful element of all is hearing someone’s story. In one recent study, people become less extreme in their views if they’d heard a personal narrative from the other person. That remained true even six months later. “It was like, ‘Now that I’ve seen you in the flesh, or otherwise imagined your circumstances, I grow softer toward you,’” says Laurin. “‘I still may not entirely agree with you, but I can see where you’re coming from.’” Cameron agrees.

“There’s no question in my mind that when people encounter each other, face to face, one on one, we have a remarkable capacity to resolve our differences, and we discover we have more in common than we think we do.”

Here, though, is an important detail to remember: it’s possible to reduce partisanship too much. There’s an optimal level of partisanship in any system, and it’s not zero. A healthy political ecosystem needs viewpoint diversity. It needs the productive friction of opposing opinions, and that applies to everything from a marriage to a parliament. A lot of the same rules apply. Compromise solutions that end up with both parties marooned, dissatisfied, in the mushy middle, are suboptimal. Plus, most people, just to maintain their own integrity, have lines they’re not willing to cross. As Laurin puts it, “There are some ideas we don’t want to get closer to.”

“In politics, some degree of partisanship is a good thing. You can’t have a democracy without it,” says Cameron. (Indeed, too little distance between parties is often a sign of collusion/corruption – that the governing party is in some way “paying off” the opposition to toe the line.) “If you’re not partisan enough, you’re not going to get elected – and even if you do, you won’t be successful in parliament because you won’t have the discipline to sacrifice your own interests and take one for the team. On the other hand, if you’re too partisan, you can’t listen to the other side, and you can’t negotiate effectively with others; you become a flame-thrower, as we say. That’s unhelpful and it can turn off voters.”

These days the danger is clearly too much partisanship, not too little. The perils of over-partisanship spring into relief in times of instability – like when a country faces a sudden external threat. A divided home side has no hope against a more powerful aggressor.

“I think we’re seeing that in this moment right now,” Cameron says. “There’s an extraordinary coming together of our country today. People are saying, ‘We need to be strong, we need to express our pride in our country and defend it and not allow it to be taken away from us.’ And suddenly all the polarization seems out of place. I think that what Trump has done has served as a lesson for how we move forward: we rally around what unites us.”