In January, we asked readers to help us honour UBC’s unforgettable professors by sharing a story about a teacher who had made a big impact on them. We were moved by the many stories that came in, submitted by alumni who had graduated in every decade since the 1960s.

This article features only a fraction of all the incredible professors and instructors whom our readers nominated. Some of these profs have passed on, and a few others now teach at other universities. Yet all of them loom large in the hearts and minds of their former students. Here are 14 reflections that highlight just some of UBC’s most beloved professors — amazing scholars, mentors, and humans whose impact continues to be felt today.

CHARISMA PERSONIFIED:

Dr. Malcolm McGregor, BA’30, MA’31, LLD’83 (Classical Studies)

It was the late 1950’s and I was in my matriculating year at high school. A professor came from the university to help pave the way for us. I say “the university” because, at that time, UBC was the only university in British Columbia and just about the only one that any of us would consider attending.

The visiting professor was Malcolm McGregor, head of the Department of Classical Studies. His arm was wrapped in a cast as a result of some mishap, and he was able to regale us with details of his tragedy. The man was engaging, rife with charisma.

Fast forward to my first year at UBC. Plans for future studies demanded that I take Ancient Greek, which Dr. McGregor taught. That first year was enough to convince me to major in Classical Studies. Each day he would come into class wearing a teaching gown. Since most classes were at 8:30 in the morning, his gown was clean, but it didn’t stay that way. He roamed around the classroom, often leaning against the blackboard, collecting a coating of chalk dust.

Dr. McGregor always went to coffee with us after class, in the Auditorium Building. I once took the opportunity to complain to him that I was working as hard on Greek as I was in all my other four courses. “Good,” said he. “That’s what I expect.” And he did, but I was happy to do it.

There was a professor named Willie who taught second-year Greek. Regularly the two instructors had their comical disagreements. The two classes took place at the same hour, in separate rooms within Buchanan. At the end of one of Willie’s classes, he explained that, depending on which dialect was being spoken, there were two pronunciations of thalassa, the Greek word for sea. We were reading Xenophon’s Anabasis, the story of the march of soldiers across Asia Minor and Mesopotamia. There is a dramatic point when the soldiers come over the rise and glimpse the sea. “Thalassa, thalassa!” they exclaim.

Said Willie: “Dr. McGregor will tell you that they said ‘talassa,’ but that’s not right. They pronounced it ‘t-hall-ash-a.’”

At that moment the back door flew open. In popped a shock of grey hair over a chalk-coated gown, a wagging pointer wrapped in scuffed electric tape, and a voice that said: “Uh-uh, Willie! Talassa, talassa!”

BLAZINGLY POPULAR:

Dr. Walter Gage, BA’25, MA’26, LLD’58 (Mathematics)

I struggled with first-year math. A friend suggested I attend Dean Gage’s math class.

You had to get there early to get a seat. Fire laws were strictly ignored as the class grew into the aisles.

Dean Gage made my first year for me.

His wit and direct teaching methods were the best I ever had at UBC.

SEEDING NEW INTERESTS:

Dr. Janet Stein (Botany)

I was a first-year Chemistry student in 1976 who chose to take what I thought at the time would be a dreaded life science elective — Botany 100 (or maybe it was 101). I had always avoided biology courses as I loathed taxonomy.

Dr. Stein was a fabulous lecturer and a very warm and engaging person.

She certainly changed my mind about life sciences — so much so that I took additional Botany courses in my second year and ended up changing my degree program to Botany.

TEACHING FROM THE HEART:

Dr. Floyd St. Clair (French)

Thousands of UBC alumni from the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s would remember Floyd St. Clair, who specialized in 19th-century French Literature and taught a Survey of French Literature course, which drew 300+ enrolments each year.

This was before the age of “Rate your professor”: word simply spread by mouth that this was a “must take” class taught by an extraordinary teacher. I only took one course from him (the 19th-century French novel), but he directed my Honours thesis on Émile Zola.

Floyd taught us to read between the lines of a literary work of fiction: there was so much going on beyond the simple plot line! He connected personally with all his students and corrected all their essays (quite a feat given the number of students he had). He stayed in touch with many of his former students, inviting them to delicious meals he cooked himself at his house. Floyd was a truly outstanding teacher, remembered for both his intellect and his heart.

SPOTTING DIAMONDS IN THE ROUGH:

Dr. Fok-Shuen Leung (Mathematics)

There are too many stories to share, but one that sticks with me to this day was watching Fok patiently chatting with a group of first years about philosophy — all fairly naive stuff. At the time, I (naively) wondered how he wasn’t terribly bored or annoyed, even as he listened with interest to the students.

It’s occurred to me many times over the years that this encapsulates exactly what makes Fok a remarkable teacher: both the wisdom and mystique that he brings to his teaching, and a humility and willingness to look for the sparks of wisdom in everyone, even his youngest students.

ACADEMIC CHEERLEADER:

Dr. Carmen Mathes, PhD’15 (English)

I had been told in high school that my writing style was insufferable, that I’d never be able to earn my diploma, let alone accomplish anything else. So when I took Professor Mathes’ course (WRDS150) as my English requirement, I was simply hoping to pass it.

Professor Mathes saw me — to this day, I wish I knew what it was that she saw — and she encouraged me to submit my first paper to the undergraduate conference that year. I did, and I got in.

I was up there on the stage, a kid who never spoke, presenting next to literal grads, and she was there, smiling at the back.

I got into the next conference after that and, from her encouragement, have taken up writing my first book.

Professor Mathes saw me at a time when I felt invisible. That semester with her informed how I showed up for the rest of my degree and shaped my career.

A TEACHER’S TEACHER:

Mollie Cottingham, BA’27, MA’47 (Education)

Mollie Cottingham taught the 1964-65 pedagogy classes for both English and History. She was remarkably prepared and very generous with her time and suggestions for how to deal with teaching difficulties.

She also did something remarkable for me, which I took into my 28-year teaching career. I was upset about something to do with school libraries and did some research. At the next class, I asked Professor Cottingham if I could present what I had found. She said rather hastily that there would not be time because she had a full plan for the class. I was disappointed but accepted her decision.

Professor Cottingham then started the class by saying she had just made an error and had refused the offer of new information from someone in the class. She asked me to present my research, and then she told us to always be sensitive to the enthusiasm of students even if the planned lesson was disrupted. We were all so impressed, and I am sure I was not the only person who remembered this as we forged on in our teaching careers.

GRACE IN ACTION:

Dr. John Grace (Chemical Engineering)

If decades after teaching them, your students are currently reflecting on your ability to make them think and solve problems for themselves, then you haven’t left an impact, you’ve left a legacy.

Recently, I found myself reflecting on Dr. John Grace and his teaching style during a meeting at work on how to improve team engagement and foster a culture of mentorship in our department. Dr. Grace was the type of teacher who used the Socratic method so well that any feeling of intimidation due to his credentials or his ability to scrutinize your answer melted away as just an anxious thought.

I can still remember my fourth-year group project, where I and nine other students were tasked with designing a chemical plant. Dr. Grace was our advisor, but he acted as if he was just another engineer or design student on the team — and not as if he was the Canada Research Chair on the subject!

In discussions he approached our design problems as if he was also looking at them for the first time and with similar enthusiasm. If a suggestion was off, he could see the thought the student was starting with and, through questions, steer them towards correcting it or getting it to the doorway of the solution. His approach made it rewarding to try, even if you might be wrong.

Even then, I was aware of the patience required to do all this, and it made me think he was well suited to his name! It was clear that Dr. Grace loved the subject matter and that he equally loved watching people learn it and come to master the subject through solving problems for themselves.

SETTING THE STAGE FOR GROWTH:

Dr. Alexander Globe (English)

During the first class of our third-year English Lit course, Professor Globe announced that one third of our final mark would require a group project. The group would perform several scenes from a Shakespeare play — in costume, all lines memorized!

By the second class, a third of the students had promptly switched courses. Those of us undaunted remained and rehearsed. I did wonder at some point if I was mad to attempt this. So too did passengers when I frequently rehearsed my lines out loud on the bus going up to campus.

As the semester progressed, our group of eight withered down to three. We were slated to “perform” Henry IV, Part I in a Buchanan classroom, which would include frantic costume changes in the hallway. I feared our efforts would be hopeless.

To my astonishment, we got an A! One person in our group even decided to switch to theatre. I wasn’t going to go that far, but I did accomplish something I never dreamed I could.

LEADERSHIP LESSONS IN THE LAB:

Dr. Kevin Smith (Chemical Engineering)

Professor Smith was more than just a teacher — he was my mentor and PhD supervisor, shaping not only my academic journey but also my professional approach to research and leadership. His honesty, integrity, and vast knowledge made every day in the lab a lesson, not just in science but in how to conduct oneself as a professional.

One moment that stands out was during a particularly challenging phase of my PhD research. I had spent weeks troubleshooting an experiment, feeling frustrated and uncertain. Instead of offering a quick solution, Professor Smith sat down with me and asked a simple question: “What do the facts tell us?”

That moment was a turning point. He taught me to strip away assumptions, focus on the data, and approach problems with clarity and precision. It was a lesson not just for that experiment, but for my entire career.

Beyond research, he led by example — showing me how to communicate complex ideas simply, to uphold professionalism in all situations, and to lead with fairness and respect. His mentorship shaped the way I think, work, and lead today, and for that, I am deeply grateful.

REAL TALK WITH A UBCO PROF:

Norine Webster (Management)

Norine is a courageous leader who demands a backbone out of her students. Have an opinion? Great, back it up. Have a story to tell? Great, teach the class what you learned. Discover something interesting about the industry you’re studying? Great, defend why it’s important. She got students to leave their comfort zones as effectively as Harvard lecturers I have witnessed.

Norine taught that thoughts are fleeting, thinking is hard, and research is even harder, but if you do it well and aim to be challenged — so that your strategy or thesis can be forged like steel instead of thin like tin — you might find an opportunity.

She helped us understand that ideas are little and sometimes meaningless without formidable research and an understanding of the forces surrounding them. Maybe an idea is worthy of building a business around, but you better have an entry strategy and contingency plans prepared — and you better be willing to scrap them when things change.

Forget your USB stick or have a file issue before presenting? Well… investors are waiting. You better go from memory in one minute — or they’re walking. That’s reality. She taught reality, preparing students for a career in the business world.

I have worked with peers from universities all around the US, and I have rarely met students as tough and prepared as the ones coming out of UBCO because students were held accountable in small class sizes and could not facelessly skip by.

I firmly believe if more professors taught like Norine did and ditched the niceties, students entering the business world would be much more prepared.

From Shanghai to Atlanta to Milan, I took a lot of what Norine taught our class with me. It helped me exit a business and plan the next one.

BRINGING LEGAL THEORIES TO LIFE:

Dr. Robert Russo, BA’94, LLB’04, LLM’06, PhD’12 (Law)

One of the most memorable moments occurred when I was wrestling with a particularly dense tort law concept. Torts can be intricate — balancing duty of care, causation, and damages isn’t always straightforward. I remember feeling stuck on how to apply a specific legal principle to a real-world scenario, so I reached out to Professor Russo for guidance. Instead of just telling me what to do, he walked me through the fundamentals step by step, asking thought-provoking questions that helped me see the underlying logic of the case law.

As I explained my confusion, he provided an example that vividly brought the abstract legal theory to life: he drew a parallel between the duty of care in torts and everyday moral responsibilities, illustrating how the concept shapes not only legal outcomes but societal expectations.

It was an “aha” moment for me — I realized that tort law isn’t just about rules and statutes, it’s about understanding the social contract we all participate in. By the end of our conversation, I felt confident enough to write a well-reasoned analysis that I was truly proud of. Even more than that, I came away with a deeper appreciation for how law intersects with real human experiences. That shift in perspective — seeing torts as more than just “case law” — is something I continue to carry with me as I navigate my legal career.

REVEALING HISTORY:

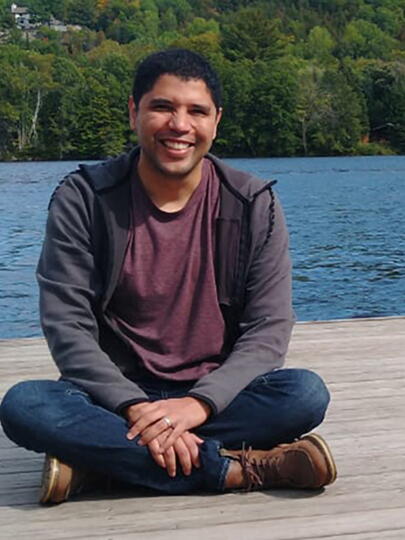

Dr. Paul Krause (History)

I still remember the sunny afternoon during the fall semester in 2011 when I walked into Professor Paul Krause’s office to discuss my final paper for his fourth-year American history class. I was curious about his interest in African-American history, and why he had dedicated his life to learning about the topic.

I didn’t know it then, but his answer would go on to shape both my academic research and my outlook on life, and propel me on a journey to unearth my own history.

Professor Krause told me about the history of his Russian Ashkenazi Jewish ancestors, who had fled anti-Jewish pogroms to find a better life in Poland, and later Pittsburgh, where his father was a doctor for the city’s steel mill workers. He explained how he saw commonalities between the suffering of his ancestors, who were forced to migrate to new lands, and the struggles of the Civil Rights movement — a movement that was also forged with the memory of the Holocaust.

He then asked me about my background. I paused, unable to answer his question in any detail. I was born in Vancouver, to parents from Fiji who had migrated to Vancouver in the 1960s, and had ancestors who had lived somewhere on the Indian subcontinent. Beyond that, I said, I didn’t know what happened and why my family ended up in Fiji. He told me I could figure it out if I wanted. Up until that conversation, I had never considered that I could use my personal history as a way to understand the world.

After I graduated from UBC, I went on to study law at SOAS, University of London, where I met experts on migration history who helped push me in the right direction. I eventually found my great-grandfather’s emigration pass from the British Raj to Fiji, explaining his ethnic origin and birthplace, and revealing the unique relationship my family had within the British Empire.

I then connected with an expert at the University of Edinburgh, who was able to help me contextualize my family history within the broader policies of the British Empire. These conversations and continued research have led to an article co-authored between myself, Dr. Marina Carter, and Dr. Crispin Bates entitled, “The Alchemy of Ancestors: a Pashtun-Fijian Odyssey within the British Empire,” to be published this fall in an anthology by Cambridge University Press.

None of this would have occurred if Professor Krause hadn’t taken the time to share his connection to the research and to earnestly care that his students engaged with the material.

In the Prison Notebooks by Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci, he explains to his readers that “the starting point of critical elaboration is… ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of the historical processes to date, which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory.” Professor Krause helped me to create the filing cabinet for my inventory. For this, I am forever grateful.

UNFORGETTABLE CHANGEMAKER:

Dr. Kenneth Stoddart, BA’65, MA’68 (Sociology)

In my second year at UBC, I took an introductory sociology course. I had no idea what sociology was or the impact the professor, Dr. Kenneth Stoddart, would have on my life. How could one professor or one sociology class make any real difference to me? Well, that one class and that one professor transformed my life.

Dr. Stoddart was an associate professor at UBC from 1972 to 2003. With his casual and approachable demeanour and conversational style, he taught sociology through storytelling, film, and writing. He asked his students to analyze and reflect on our role and place in the world, and how the world interacted and impacted us. These were dynamic and exciting discussions, time flew by in every class, and what we were learning was nowhere to be found in the generic textbook. This was something special.

Dr. Stoddart showed us how sociology was relevant to our everyday lives. It was a field of study that wasn’t just “out there” in the world with outdated theories and esoteric facts and dates to memorize. Rather, the beauty of sociology was that it was accessible to all of us — whoever we are.

His unique approach included us writing our own autobiography, using movie clips to demonstrate sociological concepts, and drawing from everyday examples that we often took for granted. In one class, Dr. Stoddart asked us to consider what would happen if we didn’t follow social norms and rules — like standing the “wrong way” in an elevator or deciding to sit next to the only other person on a bus. While these examples generated lots of laughter — a common feature in his classroom — he was teaching us how to think, to reflect on our own lives, and to consider existing societal values, norms, and the typically unexamined status quo.

Dr. Stoddart sparked in me, as an undergrad, a keen interest and boundless curiosity about sociology. I found myself fascinated by this field of study and when it came time to declare my major, there was no question — I would choose sociology. Or rather, sociology chose me.

Many years later, I returned to UBC to pursue graduate studies in the field. When I was assigned to be Dr. Stoddart’s teaching assistant for his Introduction to Sociology course, I felt honoured. This time, I was on the other side of the lectern and got to see how the special sauce was made. It felt like things had come full circle. Dr. Stoddart taught and inspired a new generation of students, and they were dazzled just like I had been a decade before.

Sadly, Dr. Stoddart passed away in October 2006, but I will never forget how he brought magic to his classes. He introduced me to the world of sociology, shaped my way of thinking, and, ultimately, inspired me to think about possibilities beyond anything I knew or could imagine at the time. That is the transformative power and potential of one person, one professor, and one class.