Inside Out

UBC’s Global Reporting Centre stops traditional "parachute journalism" in favour of empowering local voices.

“99.999 per cent of Germans don’t want you here.”

MOHAMED AMJAHID LAUGHS, reading from a piece of anti-immigrant hate mail. Amjahid is not an immigrant – he’s a 32-year-old native of Frankfurt – but that doesn’t seem to matter. His skin is brown. His name is foreign enough. And the emails pile up, sometimes hundreds in a day.

But he laughs, and the audience laughs with him.

This is “Hate Poetry,” an evening of humour and incredulous eye-rolls, where German journalists turn xenophobia into sketch comedy to highlight the growing nativism and rise of the right wing in 21st century Europe.

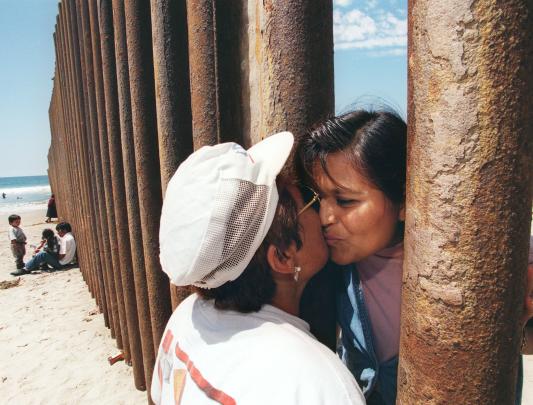

The scene is hyperlocal – if you weren’t in the room, you wouldn’t have seen it were it not for the digital storytelling project Strangers at Home. An initiative of UBC’s Global Reporting Centre (GRC), Strangers at Home offers unique, locally told perspectives on the state of attitudes towards immigrants in modern Europe.

But it’s not just the stories that stand out, it’s the way they are told. The short films are authored by the subjects themselves. Rather than going the traditional route of reporting on the subjects, the GRC is reporting with them, providing production and technical support, but allowing the subjects to write and direct their own tales.

This new kind of experimental reporting is called “empowerment journalism,” putting control in the hands of the first-person storyteller. “Hate Poetry” is just one of 10 short documentaries that make up Strangers at Home, ranging from Roma life in Macedonia, to migration in Greece, to the intersection of fascism and charity in Italy. Born from a desire to challenge traditional methods of international reporting, empowerment journalism is an attempt to overcome the blind spots and bias inherent in having local stories told by outsiders.

“There seems to be a growing sense among journalists that traditional foreign correspondence is antiquated,” says Peter Klein, professor at the UBC School of Journalism, Writing, and Media, and executive director of the GRC. “It has traditional neocolonial trappings that most journalists are unaware of. You’re basically sending a privileged, usually white, western reporter to some far off place to see the poverty or disease or war or whatever, taking something from that place, and bringing it back home and telling everybody about it in a way that’s relevant only to them. There are a lot of missing perspectives and missing voices in that model.”

By supporting locals in telling their own stories about the intersection between immigration and human rights in Europe, Strangers at Home uses empowerment journalism to offer a much different, more personal perspective on stories that affect the local community but still carry ripples of international relevance.

Such experiments are unusual in the competitive media landscape. The large companies that dominate the markets are profit-driven, lacking the stomach and the expertise to take risks. Independent media simply lack the funding, relying on donations and grants just to keep afloat. So it falls to rare organizations like the GRC to innovate in the reporting arena.

Built on a three-tier system of studying global journalism, experimenting with reporting techniques, and teaching their findings to the next generation of reporters, the GRC resembles a lean start-up as much as a news organization. “Most media organizations just produce journalism,” says Klein, who officially founded the GRC in 2016 but began creating its content nearly three years earlier. “But because we’re part of a university we want to take advantage of that, to really bring some scholarly rigour to what we’re doing.”

To blend scholarship with practice, the GRC teams reporters and academics who work together on stories through every phase of the project – from conception to field reporting to critical analysis of their techniques. This replaces the traditional model of reporters simply interviewing academics for a small slice of the story.

One challenge for the GRC has been addressing the issue of “fixers” in the practice of “parachute journalism.” A Western reporter drops into a place they know little about and relies on a local journalist (the fixer) to translate the language and make the connections needed to tell the story. But it’s an exploitative relationship that favours the outsider’s narrative at the expense of the local, often marginalized, community’s perspective. “It’s easy and convenient to use fixers,” says Klein, “but once you take that traditional methodology out of the equation, then you’ve got to come up with new things. You’re sort of forcing yourself to experiment. So we’ve intentionally put ourselves in this awkward position of saying let’s try to do global journalism in a new way.”

When Strangers at Home was first proposed in 2013, its working title was History Repeated, focusing on the rise of right-wing nationalism similar to that which brought the Nazi party into power eight decades ago. The initial plan followed the traditional path of international journalism: get some funding, go to Europe, interview subjects, and tell the obvious story – the nationalists rise to power, the world looks away, and we unleash another holocaust.

“That was an interesting historical touchstone from a simplistic storytelling standpoint,” says Klein. “But then we started talking to scholars and experts on refugee issues, experts on xenophobia and nativism and the rise of the right, and consistently what I heard from them was, ‘Please, please don’t do the predictable story of history repeating itself.’”

As it turns out, Nazi-era Germany is a poor historical analogy for what’s happening in today’s interconnected world, and the various forms of racism and xenophobia throughout Europe are too diverse to be understood in all their complexities by outsiders. Foreign journalists often approach these issues in sweeping brushstrokes, assuming there is little difference between Greece’s Golden Dawn and Italy’s CasaPound, or between anti-semitism in Hungary and anti-semitism in Sweden, chalking them all up under the simplistic rubric “the rise of the right.”

“So we thought, rather than us coming in as outsiders imposing our own view on these issues, why don’t we empower people to tell their own stories?” says Klein. “Why don’t we embrace that complexity and nuance?”

The project was renamed Strangers at Home, and the first person Klein tapped was the series’ project manager Shayna Plaut, then a PhD student at UBC who was teaching a class on human rights at the School of Journalism. With Plaut taking the academic lead, and Klein providing the journalistic support, they assembled a team that ranged from journalism students to a Pulitzer-winning producer, ultimately working with two dozen researchers, reporters, producers, technical professionals, and storytellers to help locals deliver their niche perspectives.

But to what end? What is the point of telling stories from a local perspective for an audience on the other side of the world?

Because we are more interconnected than we think. Many North Americans have attributed the rise of the right in Europe to an extension of the emboldened American white nationalists after Trump’s inauguration in 2017. But the Strangers at Home project began in 2013, and was completed in 2016, when the political climate in the United States was much different than it is today, and anti-immigrant ideologies such as the Tea Party movement seemed like they might be more of a fashion statement than an established base. These small stories from the corners of Europe revealed the roots of what soon became a global trend in nativism. Traditional foreign reporting wouldn’t have told them until the issues were on our doorstep.

The success of Strangers at Home – which has won several awards and was presented at the United Nations – led to other projects such as Turning Points, which empowered members of Indigenous communities in Yellowknife to tell their own stories about the problem with alcohol dependency in their community. The powerful documentary reimagined the newsroom as a first-person account rather than a third-person observation, illustrating the need for journalists to transition from gatekeepers of the information to collaborators with their subjects.

“We wouldn’t have done Turning Points if it weren’t for the lessons we learned from Strangers at Home,” recalls Klein. “Alcohol dependency in Indigenous communities is one of those topics a lot of people in those communities want told, but they don’t want it told in the traditional way of outsiders coming in and – intentionally or unintentionally – perpetuating stereotypes. So we handed the storytelling power over to them. Just like with Strangers, it was proof of concept that you can empower people who are not professional storytellers and get really compelling stories out of them.”

But the stories don’t come easily. Empowerment journalism is expensive, risky, and producers give up a lot of control – the occasional failure is inevitable. In traditional newsrooms, people get fired if they fly around the world chasing a story and then come back without one. Staff journalists can’t take that risk, and freelancers can’t afford to – there’s an unspoken pressure to contort your story to fit some preconceived idea that may not be accurate.

Because funding for the centre also defies journalistic norms, this issue is easier to sidestep. The GRC accepts no corporate sponsorships or commercials, relying primarily on academic backing and philanthropic support from foundations and individuals. Strangers at Home was 100 per cent crowdfunded. But so far the GRC has managed to produce dozens of award-winning projects in partnerships with leading media organizations around the world, including NBC News, the BBC, the CBC, and the New York Times.

The GRC’s biggest challenge, Klein admits, is raising operational support. “It’s great for a foundation or individual to have a connection to a documentary or book project,” he says. ‘I funded a documentary’ sounds awesome. ‘I funded the infrastructure to allow an organization to grow’, well, that’s less interesting, but it’s what we need most. You can’t grow an organization without that kind of funding, and you can’t take the risks.”

“The system isn’t designed for experimentation and failure,” he continues. “But this is the value of a non-profit journalism model – we can take risks, we can fail. As long as we can afford to fail and accept the occasional loss, then we’re learning a lot from it.”

The Strangers at Home documentary series and more can be viewed at globalreportingcentre.org