A Theory of Violence

Global sociologist Jasmin Hristov is uncovering the secretive forces at play behind land dispossession in Latin America.

They sped away from the village, as fast as their car could go on rutted roads through sugar cane fields. Stopping was not an option.

At the wheel that day was a member of a peasant organization who had been driving Jasmin Hristov, assistant professor of sociology at UBC’s Okanagan campus, and filmmaker Benjamin Cornejo to a remote village in the Mexican state of Chiapas. Hristov, fluent in Portuguese and Spanish, planned to interview families who had been forcibly displaced from their land by paramilitary forces. Cornejo was there to film the encounter for a documentary he and Hristov are making on displaced peoples.

Nearing the village, their driver was warned by phone that a paramilitary group was shooting at dwellings there. “We turned back,” recounts Hristov. “But we worried the group might catch up with us as we were driving away.”

It’s not a typical scenario for an academic researcher, yet this wasn’t the first time Hristov had been in a dangerous situation.

As part of her research unearthing how corrupt capitalism, hand-in-hand with paramilitary violence, has stolen land from generations of Latin American peasants and Indigenous peoples, Hristov has made many trips to such countries as Colombia, El Salvador, Brazil and Honduras. It’s academic work of a courageous nature that connects this professor to activists, victims of land dispossession and journalists in many parts of Latin America.

She recounts her Chiapas experience reluctantly. Not because that particular trip frightened her – she’s had more harrowing experiences doing research in Colombia – she just doesn’t want the dangers of her research sensationalized. “The risk I face is minimal compared to the people who are activists and live there,” says Hristov.

ACADEMIC EMPOWERMENT TO THE PEOPLE

Hristov teaches political sociology, globalization and human rights, gender and women’s studies, and sociological theory. Her research examines a wide span of political violence in South and Central America, including violence carried out by state forces and irregular armed groups, and the social ailments, such as sex trafficking and other abuses of human rights, arising from economic globalization.

Hristov’s research, contrary to much of the existing sociological literature, posits that land dispossession cannot be explained solely as a product of abuse of power or criminality. Neither can the parallels between the activities of armed groups and capitalist interests be considered coincidental. She has developed a novel theory of “pro-capitalist violence,” offering a new way to see and understand the secretive relationships between paramilitaries, large-scale capital, and oppressive governments.

“My fieldwork with different actors involved in these conflicts … shows that violence and legislation work in tandem towards achieving the economic objectives of capitalists, as well as those set out by international institutions such as the World Bank,” she says.

Hristov has done more than 100 interviews with victims of land dispossession. She has used those interviews to illustrate – in her books, courses and forthcoming publications – the massive human suffering and injustice that is still taking place in Latin America.

People are dispossessed of their land through market mechanisms (such as free trade agreements), judicial mechanisms (such as the commodification of collectively owned land), or through violence. Land dispossession, says Hristov, is “a process that destroys sustainable rural livelihoods and the social fabric of communities, and generates ‘surplus humanity’ – people with no livelihood and no job prospects.”

Many migrate to nearby urban centres and end up living in slums. “Given the lack of economic opportunities and the extreme food insecurity – as well as being trapped in spaces ridden by gang and organized crime violence – young people are left with few options: mainly to join the criminal world or to be victimized by it.”

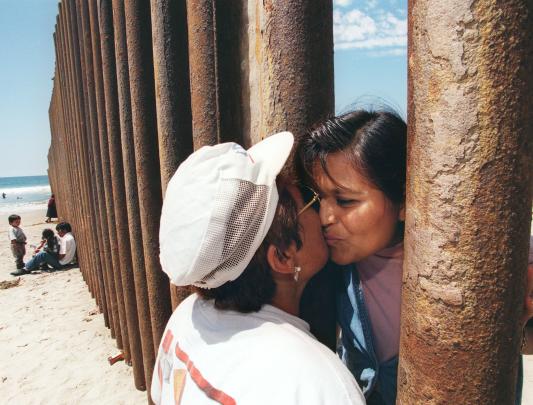

During her research Hristov heard first-hand stories from people and families involved in land struggles in Honduras and Chiapas, Mexico. Without access to land, they felt their only chance of survival was migrating to the United States and seeking asylum.

Yet the large-scale suffering propelling involuntary migration was largely invisible to the North American public until caravans of desperate immigrants from Central American countries such as Guatemala amassed at an unwelcoming US southern border, where tens of thousands of them were detained in inhumane conditions.

During the month of May 2019 alone – at the height of this flight to illusory safety – the US made 132,865 border apprehensions. By last fall, that number had dropped by 75 per cent, suggesting the Trump administration’s unsympathetic immigration policies, backed by a false narrative that the Central American wave was largely composed of murderous gangs and drug dealers, were having their intended effect.

“We often hear of explanations for the Central American exodus being centred on poverty and gang violence,” says Hristov. “While these are certainly key reasons, poverty and gang violence have a deeper structural driver, and that is land dispossession.”

lOCAL RESISTANCE

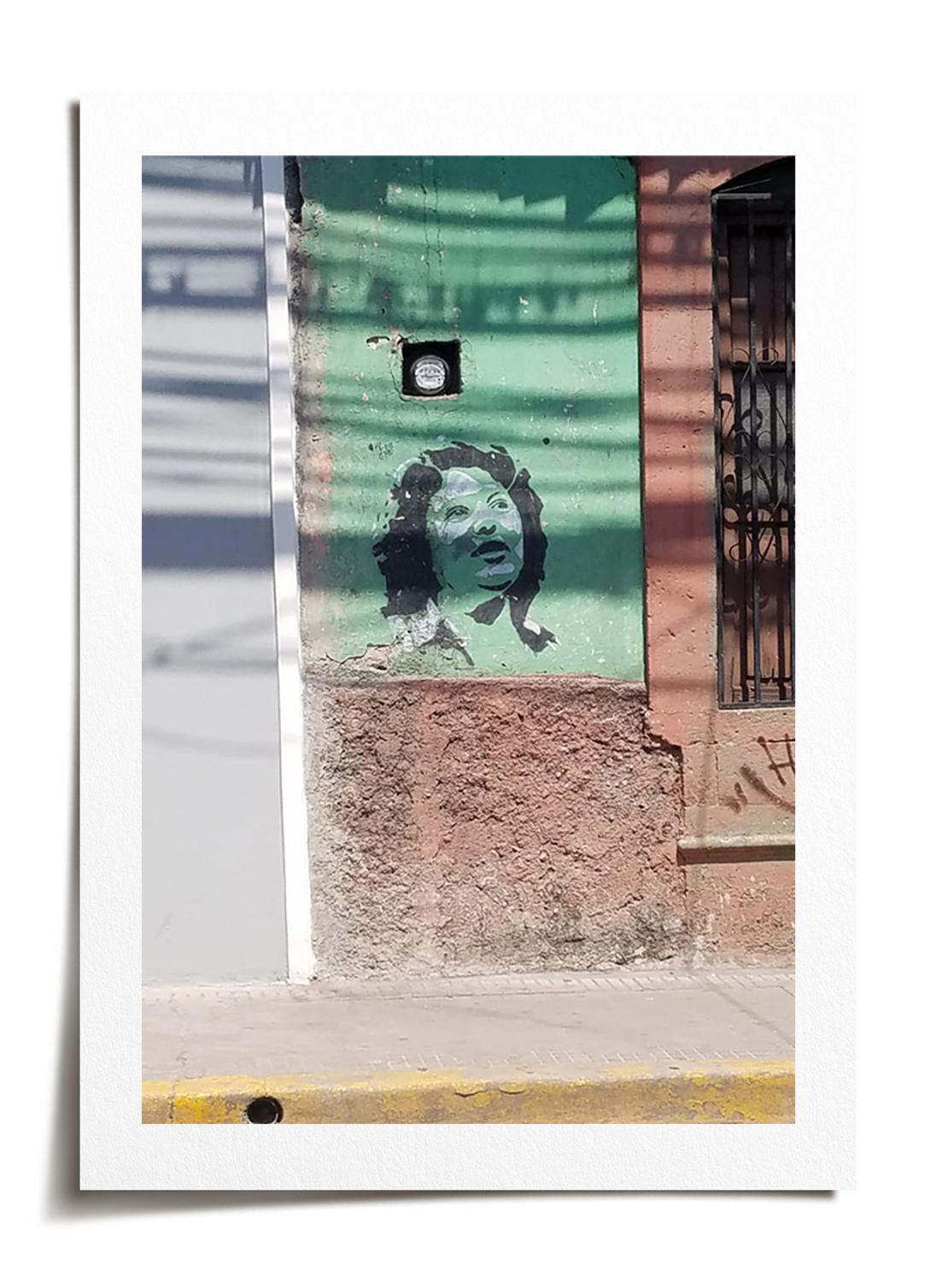

In Hristov’s office, the walls are brightened by a colourful blanket from Chiapas and other craftworks collected from research trips. The walls also sport a red flag with an image of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara and a poster of Berta Cáceres – one of Hristov’s heroes.

Cáceres was an Indigenous Honduran activist trying to stop construction of an internationally financed hydro-electric dam on the Gualcarque River, a river considered sacred by the Lenca people, whose land was threatened by the project. Cáceres was murdered in 2016 by now-convicted former members of the state military and employees of DESA, the company building the dam.

Tragically, Cáceres is one of many.

“Some [peasant] leaders are under constant threat,” says Cornejo, who met Hristov in Toronto during the early 2000s. “Some of them have been shot, kidnapped and seriously hurt. We have to be careful when we interview them and with the locations we choose.”

Just this March, as COVID-19 quarantine and lockdown measures were imposed in Colombia, local NGOs reported that armed groups had taken advantage of the situation to murder three rural activists – Marco Rivadeneira, Ángel Ovidio Quintero, and Ivo Humberto Bracamonte – and they feared more victims would follow.

Hristov regards herself as part of a small but growing number of “global sociologists.” She hopes her particular research, books, and teaching – exposing the veiled mechanisms of greed and profit behind the atrocities of land dispossession – will empower its victims in Latin America and elsewhere to find the lives and justice they deserve.

Both the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization recognize the dire situation peasant populations in developing countries face today because of economic power imbalances and a lack of protection from violence.

In 2018 the UN General Assembly approved the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas. The next step – effective implementation by nation-states – is a “huge challenge,” frets Hristov, given that those who hold power in countries such as Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico can still manipulate laws to their own advantage. “Countries in the North should support the will of the popular movements seeking change on the ground in these countries,” she says. “They should not recognize illegitimate political regimes, such as the present one in Honduras.”

AN INGRAINED SENSE OF INJUSTICE

Hristov authored Blood and Capital: the Paramilitarization of Colombia in 2009, and followed that five years later with Paramilitarism and Neoliberalism: Violent Systems of Capital Accumulation in Colombia and Beyond.

In simple terms, neoliberalism is an economic philosophy that supports a free market, deregulation, government austerity and privatization of business and services.

Yet her preface in Paramilitarism and Neoliberalism makes it clear that Hristov sees neoliberalism as a ruthless dog-eat-dog ideology that favours the rich and powerful and locks more and more people into an inescapable cage of poverty.

In Latin America, neoliberal governments and other actors often use paramilitary groups to do their dirty work. Paramilitaries – armed groups organized and financed by sectors of the elites but unofficially supported by the state – have been involved in widespread human rights violations.

Corporations too, including some in developed countries outside South and Central America, have had a hand, wittingly or otherwise, in Latin American land dispossession. Foreign corporations benefit from operating under repressive states that protect their economic interests, and some Canadian, US, and European corporations, says Hristov, “have been directly implicated in land conflicts in Latin America.” Private security forces working for such companies, as well as state security acting on their behalf, she contends, have “grossly violated” human rights among the local populations, particularly those opposed to the operations of these companies.

Hristov is angered by the misery and injustice created by uprooting people from their land and is fiercely committed to fighting the forces that generate poverty and dehumanization. The roots and impacts of land dispossession is not a field of study Hristov chose for herself. “It chose me,” she says.

She was just five when she began to have a growing sense of the injustice in the world. “When I was growing up, there was a part of me that rebelled against, or felt indignation towards the ways in which poor people in Brazil did not matter and were silenced – and had to, on a daily basis, swallow the humiliation as if they were lesser human beings than the wealthy. The bloody conflicts over land in the Brazilian north were a product of the landowning elite robbing the rural poor of their human dignity, and having the power to decide who had the right to exist.”

“I know millions of people live in these countries that are very unequal, and are accustomed to the way the poor are robbed of their dignity. And it has become as natural as the air they breathe. But it was never that way for me.”

~ Jasmin Hristov, UBC professor of sociology

It all left an indelible impression on her. “I know millions of people live in these countries that are very unequal, and are accustomed to the way the poor are robbed of their dignity. And it has become as natural as the air they breathe. But it was never that way for me.”

Even after moving to Canada with her parents as a teenager, part of Hristov always wanted to, one day, have the power to make oppressors pay for what they do.

THE REBEL IN THE RESEARCHER

Today, Hristov is the principal investigator for two major projects funded by the Canadian federal government’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

With the “Violence and Land Dispossession in Central America and Mexico” project, Hristov leads an international team that includes three UBC research assistants, two international research assistants, the documentary filmmaker Cornejo, and collaborators in each of the countries where research is being conducted.

The team is documenting the prevalence and core patterns in the relationship between land dispossession and paramilitary and/or state violence in Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador and Mexico. They have also funded and created a website that the peasant movement in Honduras can use to post news and urgent action alerts.

In her role as principal investigator for the “Human Rights Monitor of Honduras” project, Hristov is working in partnership with a Honduran NGO, the Association for Democracy and Human Rights, and 15 researchers in that country. The team is collaborating with 20 community organizations in Honduras and has conducted more than 220 interviews in the process of creating a database documenting political violence and human rights violations over the past decade.

Hristov’s research garners wide-ranging attention from the media. In 2019 she received the Early Investigator Award from the Canadian Sociological Association in recognition of the theoretically novel nature of her work and her deep commitment to human rights. But her commitment goes far beyond theory.

The central goal of her research is to contribute to social change, and she wants her work to reach audiences beyond academia. She hopes her findings will be published in journals read by policy-makers from the Canadian government and the World Bank, and wants to raise awareness about the ways economic legislation architectured by international entities such as the World Bank create conditions for investment conducive to violence and dispossession.

Hristov has also written expert-witness reports for human rights violation trials in the US and Canada related to incidents in Latin America, and she is not averse to directly challenging those in influential political positions. In December 2017, when Juan Orlando Hernández was installed for a second term as president of Honduras, Hristov gathered signatures for a collective letter to Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time. The letter asked Freeland and the Canadian government to take a stand against what was widely regarded as a fraudulent election. Hristov also was involved in urging Canada to take a stand against a wave of violence, including 30 murders of civilians, by Honduran police and military. The minister, Hristov says, took a year to reply, only to say that Canada is monitoring the human rights situation in Honduras.

Hristov acknowledges that in some academic circles there are those who are uncomfortable with her social justice approach to academic investigation – seeing her as too much the activist, rather than an impartial researcher. “Being a passionate academic seeking social transformation can be harmful to one’s career in many ways,” explains Hristov. “But it’s not something that I planned for. It’s part of me. And I can’t change that.”

The original version of this feature was published by UBC Okanagan.