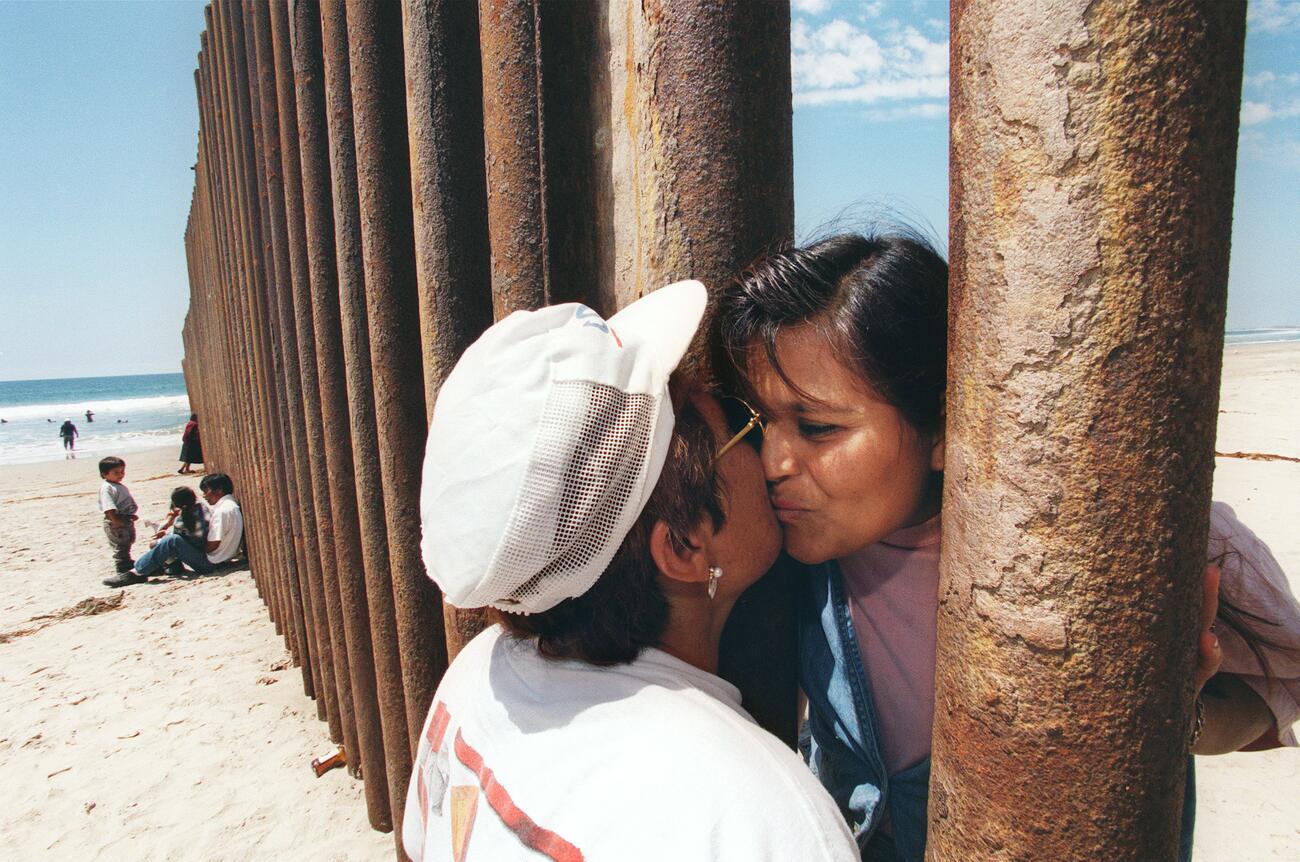

BETWEEN BORDERS. When one in every 110 people on Earth has been forced to flee, some nations respond with barriers, like “the wall” between the United States and Mexico. Photo: Getty Images, Hector Mata

New World Disorder

Syrians are fleeing. Americans are building walls. Indians are battling brain drain. And Hungary is incentivizing childbearing so that immigrant labour is no longer needed. Antje Ellermann explains why.

In the 1990s, when Antje Ellermann first turned her academic attention to the politics of migration and citizenship in liberal democracies, many of her political science colleagues considered it a niche area. Today, as millions of people seek refuge from war, poverty, and violence in their home countries, and anti-immigration sentiment has established itself as a dominating factor in politics and elections, academics are paying much closer attention to large-scale migration and its consequences.

Two years ago, Professor Ellermann founded UBC’s Migration Research Excellence Cluster. It’s a group of about 60 researchers from various disciplines who collaborate on research that “seeks to understand the causes, consequences, and experiences of global human mobility,” everything from forced displacement and statelessness to border governance and refugee integration. This year, the research cluster successfully applied to become a new centre in the Faculty of Arts – a development that she hopes will boost fund-raising efforts in support of its work.

As well as being founding director of the new UBC Centre for Migration Studies, Ellermann directs the university’s Institute for European Studies. Her current focus is on the political dynamics that drive immigration policy, and why countries faced with similar situations have adopted strikingly different policy approaches. Her new book, The Comparative Politics of Immigration: Policy Choices in Germany, Canada, Switzerland, and the United States will be published in March by Cambridge University Press. We asked her about the factors at play behind negative receptions of immigrants, and what can be done to promote peaceful and cohesive societies.

The number of forcibly displaced people is at a historic high. What are the main causes and consequences of this?

Today, about one in every 110 people on Earth has been forced to flee. Another way of thinking about this is that every two seconds someone is forced to leave their home. Armed conflict is the number one reason for this. Over the past decade, the number of major civil wars has almost tripled, civil conflicts have become more protracted and more violent, targeting civilians. We just need to look at what has been happening in Syria, Myanmar, and Afghanistan, or in Somalia, the Sudan, and Congo. A second driver of displacement is the inability of governments to ensure the political, economic, or physical security of their citizens. Think Venezuela or El Salvador. In future, we will see a lot more displacement as a result of climate change, because of widespread crop failure and the fact that entire regions will become uninhabitable because of heat, desertification, and flooding.

To make matters worse, the historic high in human displacement in the Global South has triggered nationalist responses across the Global North. The wealthy democracies of Europe, North America, and Australasia for the most part have sealed and externalized their borders, which means that those fleeing violence or poverty cannot even make it to those countries who have the fiscal and administrative capacity to offer protection.

There is a drastic imbalance between the need for, and the provision of, protection. More than half of all refugees have been displaced for five or more years, many for several decades. Millions of children grow up in refugee camps, deprived of their childhood. Of all the refugees in UN camps awaiting resettlement to countries in the Global North, only one per cent will ever be resettled.

What factors lie behind the rise of right-wing populism in Europe and the US?

Explanations of the rise of right-wing populism focus on two sources of insecurity. The first is a sense of economic insecurity, prevalent among those in the lower half and middle of the income distribution. This reflects a pattern of stagnating wages and increases in precarious employment associated with globalization, as the postwar era of sustained economic growth and rising wages came to an end in the 1970s. Increased economic insecurity is not only the result of a structural shift from manufacturing to service sector employment, but it is also the consequence of political choices made under neoliberal policy agendas that led to the retrenchment of the welfare state and the weakening of trade unions.

The second source of insecurity that is driving anti-immigrant populism is cultural change. It is associated with major societal changes over the past decades, including changes in family structure, increasing female labour-force participation, a decline in religiosity, and, most importantly, increasing social diversity resulting from high levels of immigration from non-Western and, in some cases, Muslim-majority countries.

Social psychologists tell us that humans tend to overestimate differences between “us” (the in-group) and “them” (the out-group), whilst underestimating differences within the in-group. So we end up with an exaggerated sense of difference in relation to those with different social group characteristics from us, whether that is linguistic, ethnic, or religious difference. When this process takes places in a context of widespread feelings of insecurity, heightened by the threat of terrorism, then populist leaders have an easy time mobilizing the public with anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim policy agendas.

Why haven’t we seen the rise of populism to the same extent in Canada?

It is not the case that there is no populism in Canada – think Doug Ford in Ontario or Jason Kenney in Alberta. But, at least outside of Quebec, we haven’t seen the kind of success enjoyed by anti-immigrant parties and agendas elsewhere. There are a number of reasons for this. Most important, perhaps, is the fact that no major Canadian party can afford to alienate immigrant and ethnic minority voters. The “ethnic vote” is critical to electoral success in urban ridings, especially in Metro Vancouver and the Greater Toronto Area. Canada’s electoral system amplifies the power of geographically concentrated groups such as immigrant communities, at the same time as Canada’s high levels of immigration and high naturalization rate combine to give immigrants electoral clout.

There are also other reasons that discourage anti-immigrant populism. Canada has done a better job than most countries at managing immigration. To a much greater degree than is the case in Europe or in the United States, Canada’s immigration policy privileges high-skilled immigrants. As a result, many Canadians consider continued immigration to be in the national interest. In addition, Canada’s geographic isolation allows for controlled immigration. Unlike the EU and the US, Canada does not share a border with refugee-producing regions, and relatively few refugee claimants and undocumented migrants manage to make their way to Canada.

What do you consider to be the most pressing issue in migration in Canada today?

One of the most pressing issues today is the situation of refugee claimants who seek protection in Canada, for two distinct reasons. First, in response to COVID-19, the Canada-US border remains closed to non-essential travel, including refugee claimants. Despite the fact that there is a long list of exemptions to these travel restrictions, they do not include refugee claimants. In other words, travel for the purpose of making a refugee claim is considered “non-essential,” comparable to travel for the sake of tourism, recreation, or entertainment.

A second reason why humanitarian protection is such a pressing issue is the Safe Third Country Agreement between Canada and the United States. The Agreement, which came into force in 2004, rests on the premise that Canada and the US have roughly equivalent systems for adjudicating refugee claims, which means that refugee claimants arriving at a Canadian border crossing can be legitimately turned back to the US to make their claim there, and vice versa.

In July, Canada’s Federal Court ruled that the Agreement was unconstitutional, because the US is no longer a safe country for refugees. Refugee advocates have long made the case that the many policy changes that have been implemented in the US since the Agreement came into force have undermined the integrity of the US refugee adjudication system. Even when the border re-opens, the US has in place an asylum transit ban and refuses to adjudicate refugee claims from anyone who has travelled through any country other than their own before arriving in the US. These measures were imposed by the Trump administration to counter the rising number of families from Central America who filed refugee claims in the US. The US also returns refugee claimants to Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador to pursue their claims from there, even though these countries are among the world’s most violent. As the Federal Court’s ruling recognized, Canada returning refugee claimants to the US amounts to a violation of the rights guaranteed under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Yet, despite these concerns, the government has decided to appeal the ruling, with the effect that the Agreement remains in place for now.

How can we promote peaceful and cohesive societies?

Let me share three thoughts. First, I believe that peaceful co-existence and social solidarity will only have space to develop when a society is willing to confront its dark side. If that doesn’t happen, conflicts will continue to fester below the surface, ready to erupt. Here in Canada, we are just beginning to face up to the truth about our settler colonial past and the ways in which Indigenous dispossession continues today. Coming to terms with our dark side is not a pleasant process, but it is a necessary one if we want to move forward as a society. In my view, this is the foundation on which everything else needs to be built.

Second, assuming that we want to continue to open our doors to immigrants, we need to do so in a welcoming way, valuing what immigrants have to offer us, and treat them as future citizens. Canada’s multiculturalism policy has done a better job than most integration policies elsewhere in doing so – even though it struggles to recognize the reality of racism – and we have a relatively open citizenship policy. But Canada also recruits a huge number of temporary foreign workers, many of whom will never be able to transition to permanent residence, and I don’t think this is sustainable over the long run without creating societal tensions. The pandemic has exposed how much Canada depends on the work that many of these workers perform, and we should recognize their contributions by allowing them to remain here.

Lastly, I believe that investing in our public education system is critically important. Strong public schools can serve as a kind of equalizer among kids and youth from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, and also nurture relationships that bridge social divides.