The Lee family sitting down for dinner. Albert Lee, Saint Mary’s University, Gorsebrook Research Institute, GRI_134 (1958)

A Seat at the Table

A new exhibit on Chinese immigration and British Columbia highlights belonging, racism, and resilience.

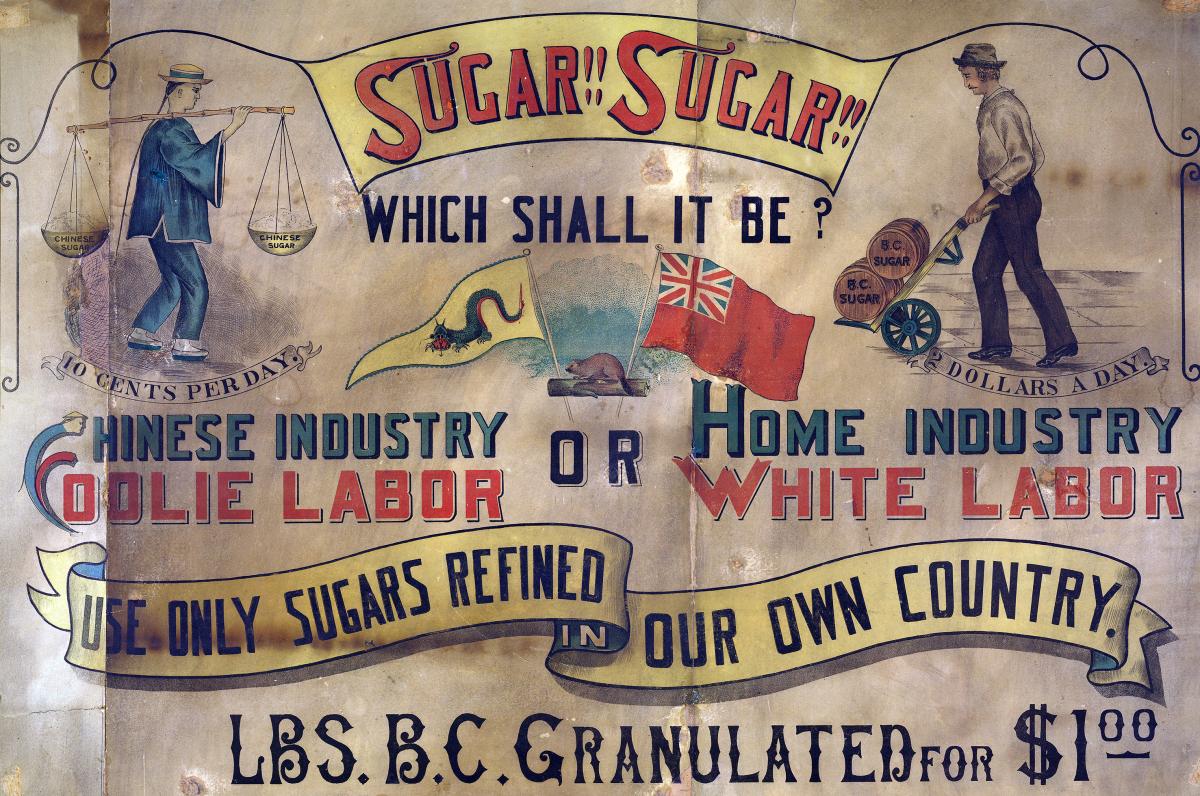

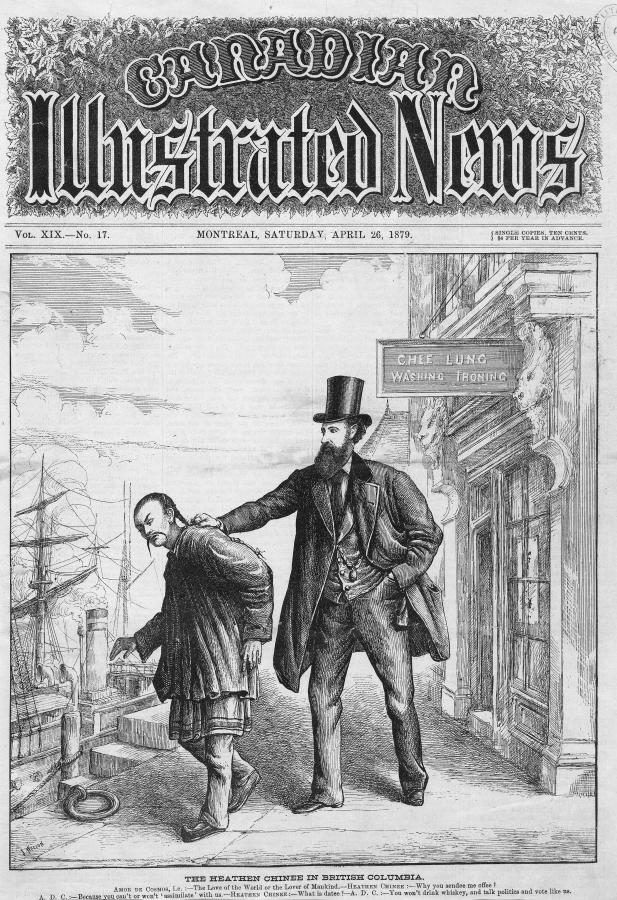

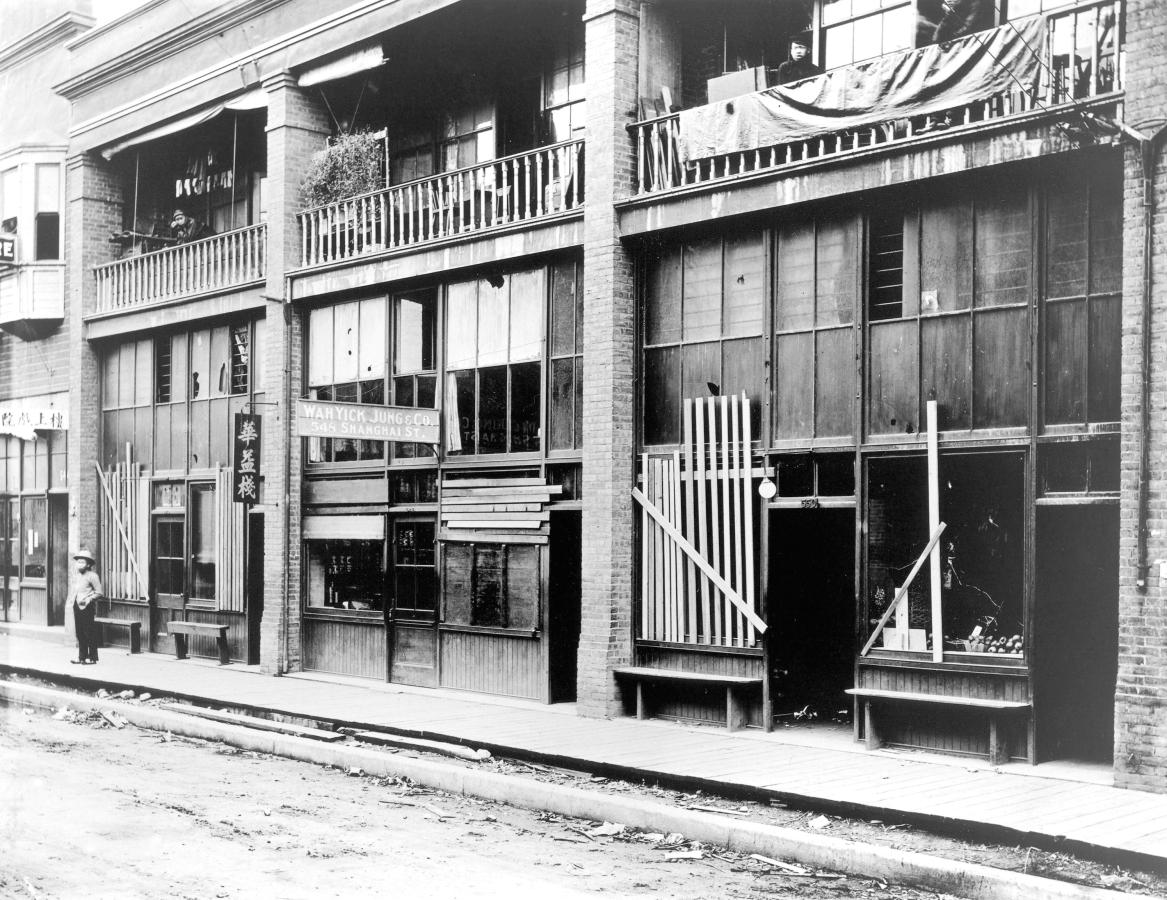

Many schoolchildren in BC today (at least those who pay attention in their history classes) are familiar with the milestones of discrimination that Chinese Canadians have suffered: the head tax of 1885, the race riot of 1907, the Exclusion Act of 1923, and segregation in housing and jobs until the 1960s. In 2006, the federal government formally apologized for this omnibus of past wrongs. In 2014, the province followed suit, and in 2018, so did the City of Vancouver.

“You have to remember the parts of the past that did damage in order to move forward together,” says UBC historian Henry Yu. Yu says these public apologies help promote a more inclusive society. Learning about histories of discrimination can also teach us how us-versus-them narratives emerge. As xenophobia takes on new but familiar expressions – including a recent surge of anti-Asian hate crimes related to COVID-19 – that lesson seems more relevant than ever.

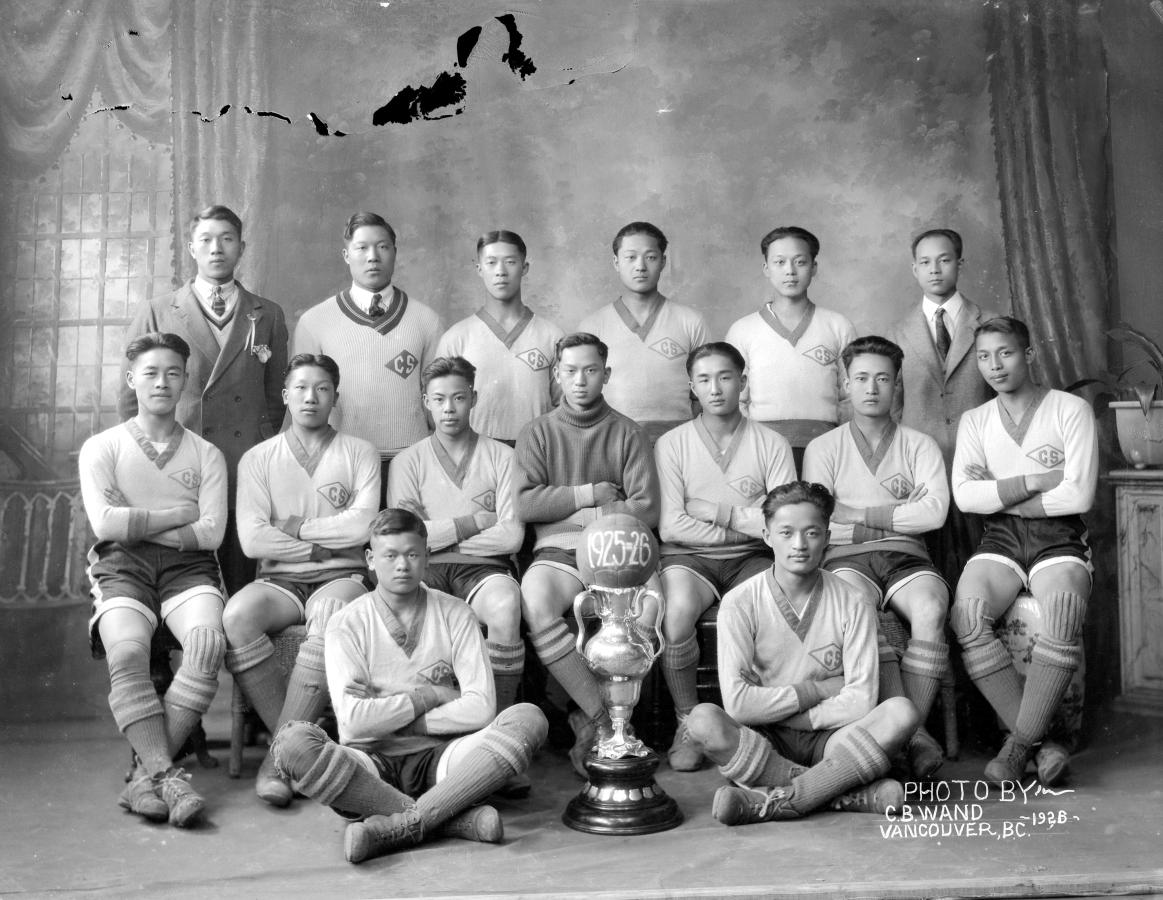

But Yu says it’s equally important to learn how victims of racism – both then and now – respond to and fight for justice.

STORIES OF RACISM AND RESILIENCE

As the co-curator of a new temporary exhibit that opened in August in Vancouver’s Chinatown, with a sister exhibition that opened in November at the Museum of Vancouver, Yu hopes to inspire audiences with stories about how Chinese Canadians battled exclusion and helped to build a better society. Curated with PhD candidate Denise Fong (BA’03, MA’08) and MOV curator Viviane Gosselin (PhD’11), these exhibits, entitled A Seat at the Table, are also the launching pad for a new multi-sited provincial Chinese Canadian Museum that will have hubs and spokes throughout BC.

“What we’re trying to do is humanize the stories and not just see Chinese Canadians as victims of racism, but instead to look at stories of resilience,” says Fong, who is completing her PhD on cultural heritage and identity in museums.

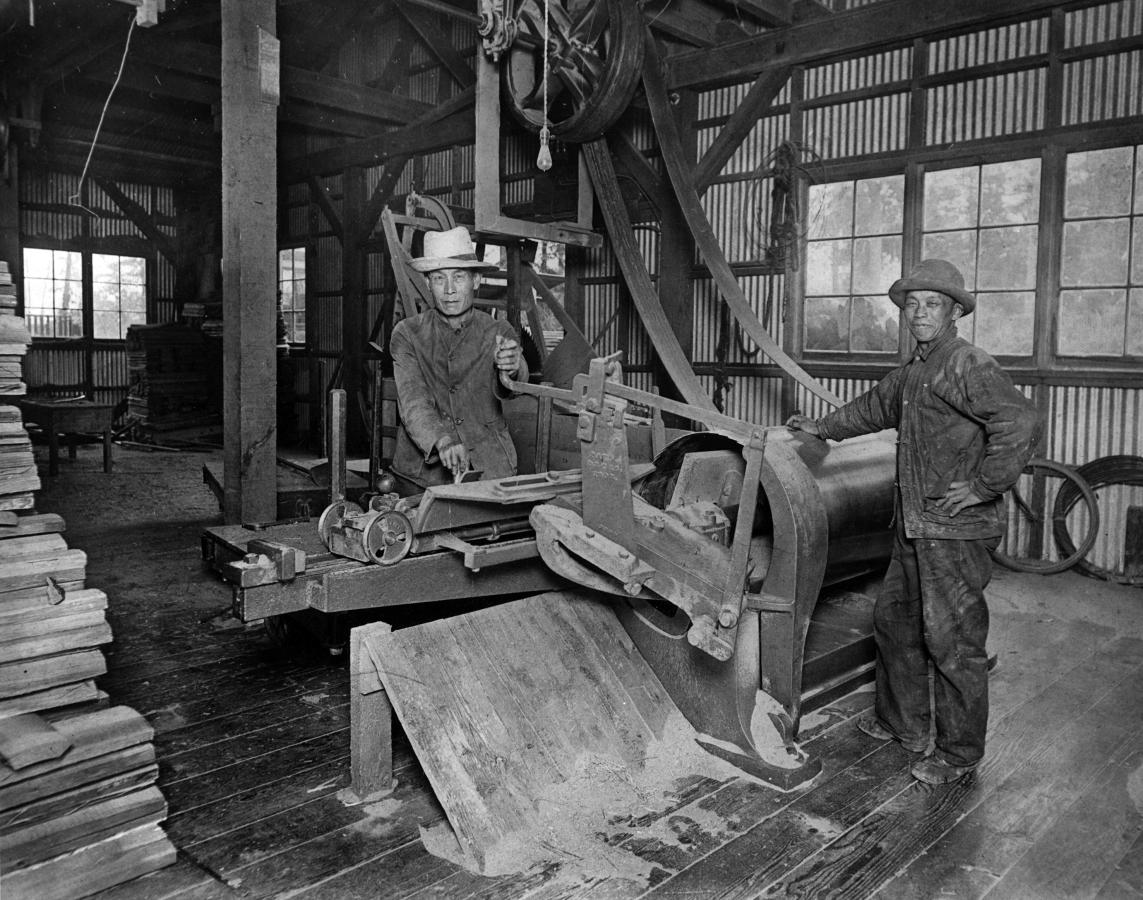

“We understand what was done to the Chinese, but often we don’t understand as well their strategies for resistance, whether it was creating alternative business networks or building partnerships with Indigenous communities,” adds Yu. “97,000 Chinese came to Canada during the head tax era. What motivated them to cross an ocean and be separated from their families?” And what continues to motivate newer waves of migrants?

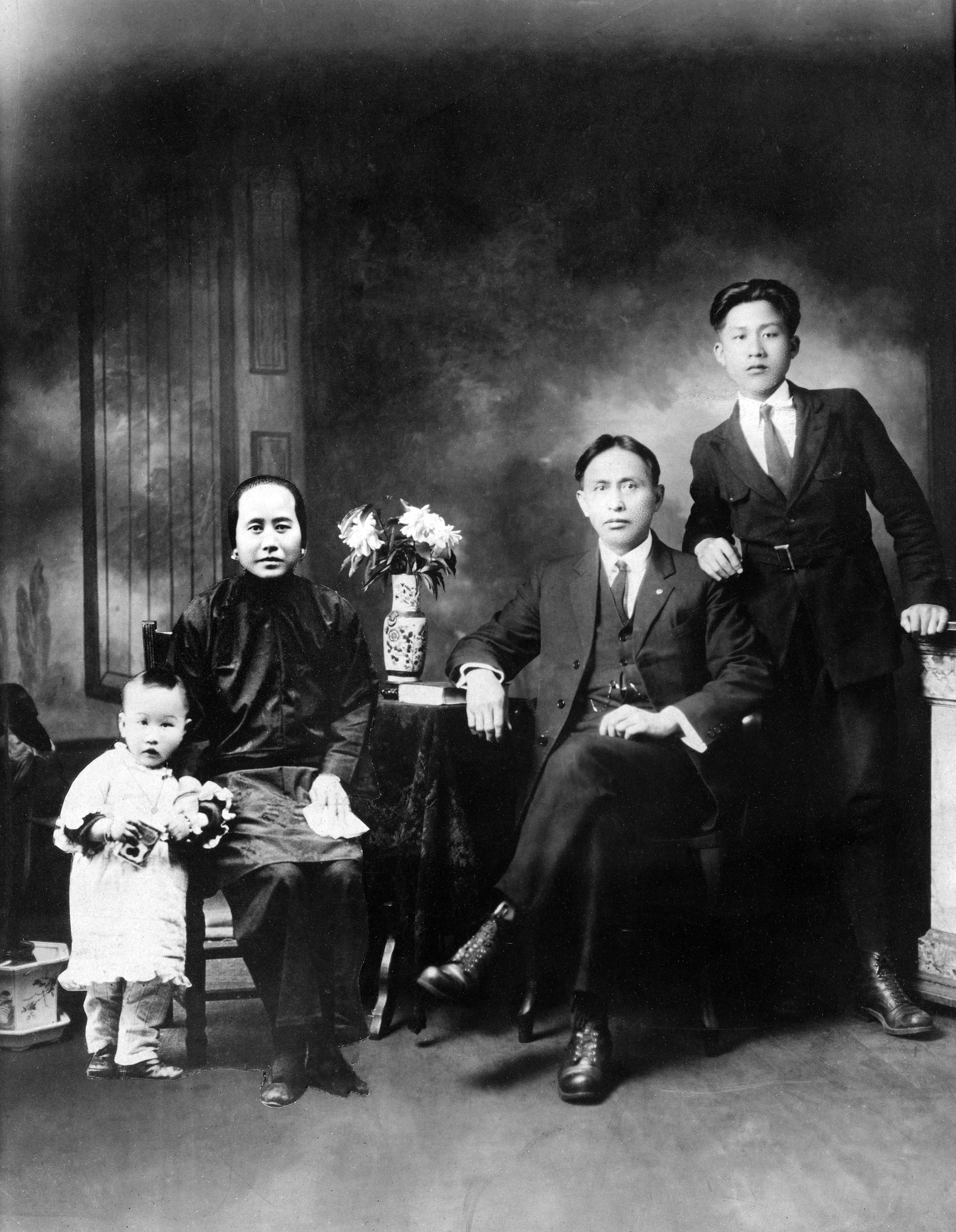

JOURNEYS OF HOPE

Both Henry Yu and Denise Fong can turn to their own family histories for answers. Yu was born at Vancouver General Hospital in 1967, the year of Canada’s 100th birthday. (He was a “Chung baby,” one of over 7,000 infants delivered by legendary OB-GYN Madeline Chung, who was for decades the only Chinese-speaking obstetrician in BC.) Although Yu’s parents had immigrated to Canada just two years earlier, making him the first the Canadian-born member of his family, he is simultaneously a fourth-generation Canadian whose great-grandfather was one of the earliest Cantonese migrants to arrive in BC in the 1880s.

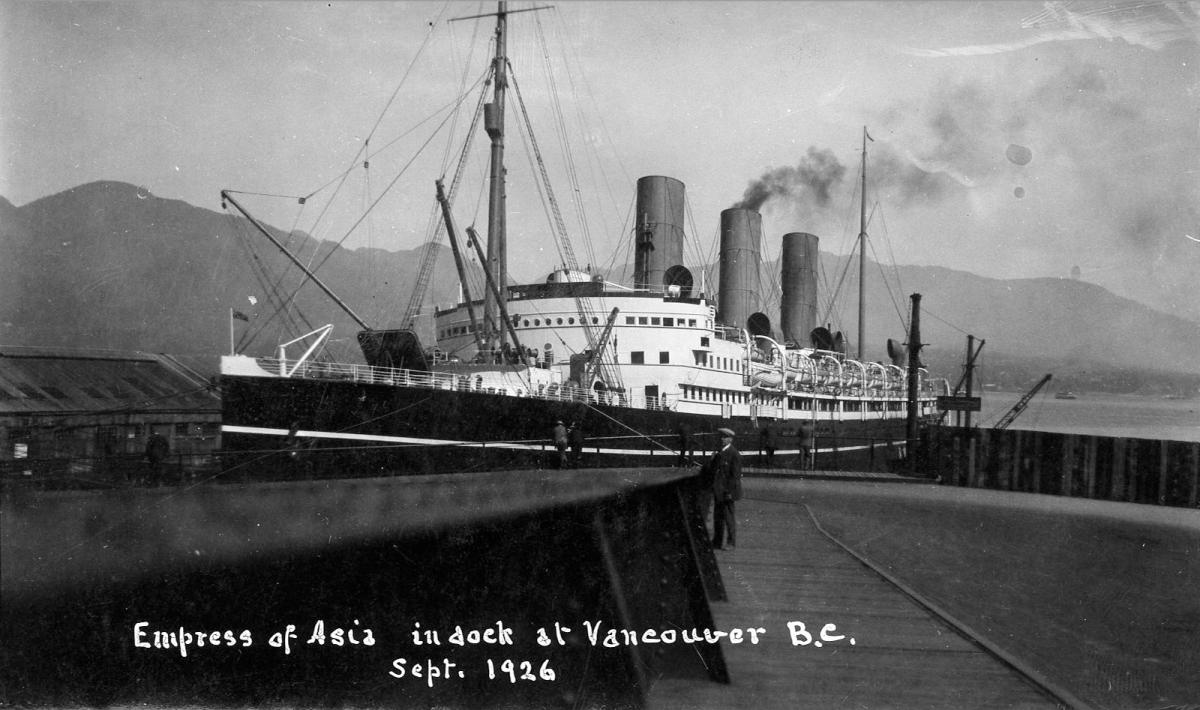

Like many of his compatriots, Yu’s great-grandfather spent his life isolated from his family, working a string of difficult jobs to send money home. He gradually saved enough to bring his four sons to Canada, one by one. The youngest was Yu’s maternal grandfather, Yeung Sing Yew, who crossed the Pacific in 1923, just before Canada shut its doors to Chinese migrants. He paid the $500 head tax (a fee amounting to two years’ wages) and spent four decades as a cook on a CPR cruise ship, returning to China just once to marry. Because of Canada’s Exclusion Act and the Chinese Communist Revolution, it was 28 years until he would meet his daughter (Yu’s mother), when she immigrated to Vancouver with her husband and children in 1965.

By then, Canadian society had evolved. Although discrimination endured in subtle and not-so-subtle ways, the legal framework of racism was being dismantled. Yu’s father, equipped with an engineering degree from a top Chinese university, quickly found employment in BC’s booming mining sector, despite speaking little English. “Within weeks he’d landed a job that paid three times what my grandfather ever made,” says Yu. “That really astounded my grandfather, who until that point had figured his son-in-law was sort of useless as a new immigrant.”

But Yu says it’s only thanks to earlier generations that his father was able to saunter into an industry that had previously been off limits. Until 1947, Chinese Canadians were banned from practicing as engineers, doctors and lawyers. “My father’s seat at the table was earned by people who fought discrimination, who literally fought for the vote by going to war for Canada. They’re the ones who made Canada a better, more inclusive place.”

Yu hopes that’s a lesson people reflect on as they look forward. “If you want to know why BC is a great place to live, but can be an even better place to live, look to those who aren’t enjoying all the privileges of living here. They’re the people who will make Canada a better society.”

NEWER WAVES OF MIGRATION

Having migrated from Hong Kong in 1990, Denise Fong’s story reflects a newer wave of cosmopolitan, educated, Cantonese migrants who bypassed Chinatown, settling in affluent places like Richmond and Kerrisdale.

Fong wanted the exhibit to reflect this more recent history of Chinese Canadian migration, but wondered how newer migrants would connect to stories about earlier migrants who built railroads, ran laundries, and endured forced segregation, when their lived experiences appeared to be so different.

But in her interviews with different communities, Fong discovered that while migrants’ trajectories and reasons for migrating have shifted, there are several common threads: belonging and identity, family businesses, a sense of being pulled between two cultures. The split family is another enduring theme that has found a new expression in the 21st century – with so-called “astronaut families” whose lives straddle Canada and Asia. “There’s been this reversal where now it’s often the families who are here raising their kids so they can have a good quality education and better upbringing, while Dad is overseas making money.”

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Fong says the exhibit and Chinese Canadian Museum broadens the idea of Chinese Canadian by incorporating a tapestry of stories from diverse communities while highlighting these universal themes. Visitors will also be invited to share their own stories of exclusion, belonging and resilience.

Yu says that reflecting the diversity of Chinese Canadian experiences is critical. “It’s no longer from eight small counties in southern China,” says Yu. “We have Chinese Peruvians who speak Spanish as a first language; Chinese from Malaysia or Trinidad or South Africa; Sino-Vietnamese and Sino-Cambodians who spent four generations in Southeast Asia before coming to Canada as refugees. Surfacing that complexity and creating an ongoing mirror is crucial.”

To that end, Yu has empowered his own students at UBC to expand on textbook histories of Chinese Canadians. For the past 15 years, instead of only assigning scholarly articles and exams, he has sent students into the community to conduct oral history media projects. The relationships they have built form a network of knowledge exchange that Yu and his colleagues have drawn from for projects like the Chinese Canadian Museum. Many of his former students now work as filmmakers, museum curators, journalists and digital storytellers, continuing to expand the story of Chinese Canadian history.

Yu emphasizes that it took 15 years of capacity-building to get to this point. “We don’t just collect histories, exhibit them, and archive them. It’s a continual process of reciprocal relationships. That’s what community engagement has to look like.”