Changing the locks on the Canada-US border

In a post-COVID world, UBC legal research may help illuminate a once-unexamined Canada-US border.

There was a time, it seems years ago now, when the Canada-US border was something you could almost ignore – when the average Canadian could wheel through a land crossing without showing so much as a driver’s licence. Then came the turn-of-the-century terror attacks – 9/11 – and the border suddenly became a tangled net of complexity and inconvenience, a place of growing paranoia, where the whole range of laws, customs and operational practices from two diverse legal regimes collided, sometimes to ill effect.

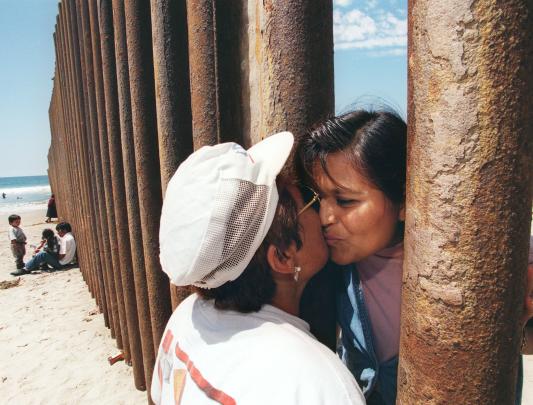

Canada and the US may be friendly neighbours, but we have conflicting priorities at our doorstep. We both want an international border that is functionally unobstructed, but still secure – one that is easy to cross for goods and people, but impenetrable for terrorists and disease. As individuals, we might also hope that our countries are protecting the rights of every traveller, businessperson, tourist, migrant or refugee. But, really, at the instant that you choose to cross the border – the very moment when you surrender the certainties of one jurisdiction and expose yourself to the vagaries of another – you can never be sure whether you are stepping onto a bridge or off a cliff.

To some degree, that mystery is understandable. In the words of UBC Allard School of Law professor Efrat Arbel, the Canada/US border is “under-examined” from a legal perspective. Sociologists and criminologists have spent lots of time thinking and writing about border policy and practice, but the written record shows that, until recently, the lawyers had walked right by.

For most people with friends, family or favourite diversions on the other side of the border, its closure has created varying levels of disappointment or dislocation. But, Arbel says, for the most vulnerable, and especially for precarious migrants and refugees, it has created a whole new threat to people’s rights and personal safety.

Arbel and her Allard colleagues, professor Benjamin Goold and former dean Catherine Dauvergne (now a VP, Academic and Provost, at SFU), have been working to change all that. In 2016, they began a SSHRC-sponsored study to shine a light on the legal issues surrounding the world’s longest undefended border. But there were few early revelations. There are so many moving people and parts, so many interlocking pieces of legislation, and so many agencies with overlapping or conflicting jurisdictions that, Arbel says, “We have yet to arrive at a coherent and complete understanding of how the law operates and applies.” And for legal research, “Usually, that’s a starting place.”

Still, by early this year they were making some headway. Among a mix of security agencies that are, by nature and necessity, reticent to share information or provide access to critical infrastructure, the Allard team was building trusting relationships and developing protocols for security and data protection – all while guarding the importance of academic independence. Having conducted significant documentary and institutional reviews, they were also negotiating with border agencies to gain access for what Goold describes as “boots-on-the-ground” research.

Then came COVID-19 – a global health pandemic that might have looked like a clarifying event. On March 20, the Canadian government simply slammed the door. At least, they closed it for most of us. Heavily invested in continuing to trade, both countries did everything possible to ensure that the trains and trucks kept crossing, while halting all but “necessary” travel for individuals.

For most people with friends, family or favourite diversions on the other side of the border, that has created varying levels of disappointment or dislocation. But, Arbel says, for the most vulnerable, and especially for precarious migrants and refugees, it has created a whole new threat to people’s rights and personal safety.

It was the human rights issue that originally attracted Arbel to this work, and it was Dauvergne who sparked the interest. Back when Arbel was a new student at Allard, and Dauvergne was then an up-and-coming professor and the Canada Research Chair in Migration Law, Arbel signed up for Dauvergne’s class and was immediately hooked. Returning to Allard as a professor after master’s and doctoral studies at Harvard, Arbel also found common cause with Goold, whose focus is on privacy rights and the use of surveillance technologies by the police and intelligence communities.

Accordingly, when the three researchers began this project, Goold says, “We were thinking about people,” and particularly how people react, interact and are affected by the laws and practices prevailing in the border environment. But as they dug into the work, connecting with the Canada Border Services Agency and the RCMP in Canada and with Customs and Border Protection in the US, they found that, even before the COVID disruption, those agencies were more focused on the mutual benefits of commerce. “They’re trying to reduce border friction,” says Goold. “They want to know what they need to do so the trucks don’t slow down.”

For refugees, however, an agreement between Canada and the US has created a situation on the border that is dangerous (according to Arbel) and unconstitutional (according to the Federal Court of Canada). The Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) was negotiated in the unnerving period after 9/11 and implemented in 2004. The treaty holds that Canada and the US are both safe havens for refugees, who should therefore have to make their claim wherever they land first. So, for example, if they try to pass through the US and claim refugee status in Canada, Canada will turn them back.

But, Arbel says, “For decades now, the US treatment of refugees, both at the level of law and practice, falls far below internationally recognized standards of human rights protection. The US is not a safe country for refugees.” Twice since the treaty was implemented, public interest groups have challenged its validity in Canada’s Federal Court, and twice they have prevailed. In 2006, a decision was overturned on a legal technicality. But on July 22 this year, Federal Court Justice Ann Marie McDonald ruled that the US is not a safe country for refugees who are sent back from Canada. She wrote: “I have concluded that imprisonment and the attendant consequences are inconsistent with the spirit and objective of the STCA and are a violation of the rights guaranteed by section 7 of the [Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms].”

As is typical in such cases, Justice McDonald gave the government six months to implement the decision, or to appeal – and the government chose to appeal. That, Arbel says, has left refugee claimants at risk, on both sides of the border. “It is a certainty, not even a likelihood, that more asylum seekers are being placed into detention in truly atrocious conditions. Detention is harmful in itself, but especially now, it is virtually impossible for detainees in the US to protect from the spread of COVID-19,” Arbel says, adding that it is a blot on Canada’s reputation and detracts from its stated commitment to protecting refugees.

Privacy is another issue under threat, and again COVID tends to make the situation worse, says Goold. Privacy, he says, is a “weak right,” easily overwhelmed by concerns for security and public health. And when weak rights are eroded during perceived emergencies – as during the pandemic – it can be difficult to re-assert those rights afterward. In the current circumstances, with fewer people crossing the border, Goold says, border officials have a much greater opportunity to search crossers and little restriction on how they use any information they might come across. The border agencies are, he says, “not very transparent.”

Transparency – or at least the increased information that Arbel, Goold and Dauvergne are ultimately able to gather – may be the greatest takeaway from the research project. As Dauvergne says, “No border agents set out to do nasty things; people are just trying to do their jobs. But it’s important to understand how individual rights are being impacted by those jobs.”

In this previously unexamined space, policymakers may find real benefit from whatever light the UBC team is able to shed.