Trailblazer

The village of Thondebhavi in Southern India is set amid lush hills, bright green palm trees, and ruddy fields sown with crops. On a blistering day in June, farmers in traditional cotton sarongs pause to chat underneath leafy trees, cows rest under sheds with palm-frond rooves, and stick-wielding herders guide a throng of goats.

At first glance, Thondebhavi seems like an unremarkable rural community, but there is something unique in the heart of this village that sets it apart: a half-kilometre stretch of road that repairs itself. The first road of its kind in the world, it is made from cutting-edge concrete developed in a lab almost 13,000 kilometres away at UBC.

Though the village lies about 70 kilometres from the edge of Bangalore, a burgeoning metropolis nicknamed “India’s Silicon Valley,” it is an unlikely site to pilot new technology. Just two years ago, the villagers’ only connection to the outside world was a mud road. It would become so mucky during the annual monsoon rains that mosquitos hovered above it, and farmers struggled to transport their crops – including aromatic flowers, pulses and vegetables – to market.

“It was in terrible shape,” grimaces Yashodamma, a middle-aged woman who sits on the elected village council. “It used to be impossible to walk on the road. Old people would slip and fall.”

The new hi-tech road runs through Thondebhavi, population 4,800, in an arc bordered by colourful one-storey houses. It connects with another new (but traditional) road built by the government, which leads to the highway. These pavements have transformed the village, making it easier for farmers transporting produce, children walking to school, women commuting to work in garment factories and anyone else with a place to go.

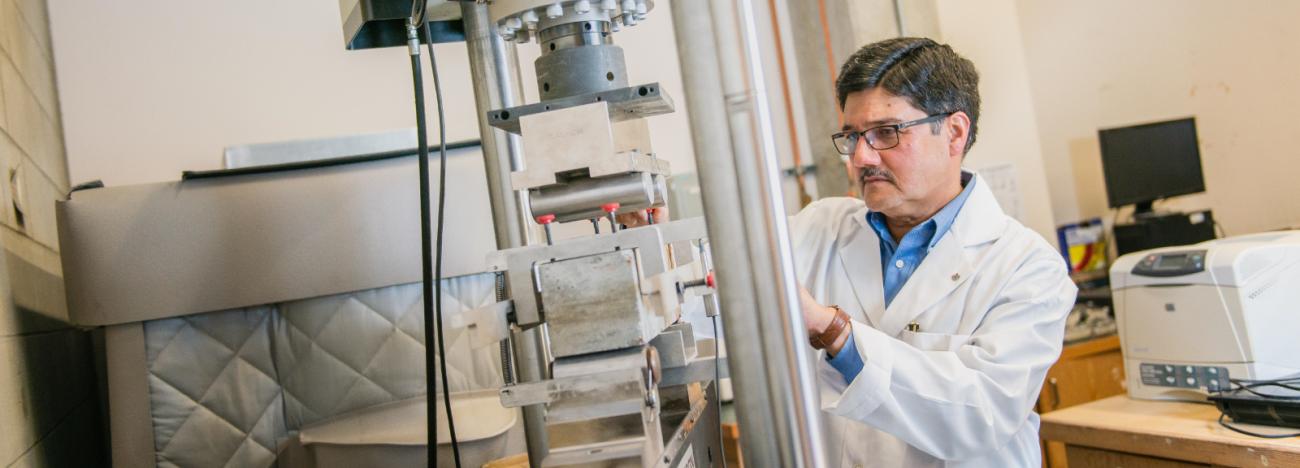

While the villagers go on their respective ways, a team led by UBC civil engineering professor Nemkumar Banthia, PhD’87, is monitoring the U-shaped road, which has sensors buried inside and is an active research project. “For this little village in South India to have the most advanced road system is very exciting for me,” says Banthia, who sports a tidy moustache and goes by the nickname “Nemy.” He wanted to pilot the technology in Thondebhavi because he was born in an Indian village without roads. “We used to go bike and we had no roads to actually bike on,” he laughs.

Banthia is the CEO and scientific director of the India-Canada Centre for Innovative Multidisciplinary Partnerships to Accelerate Community Transformation and Sustainability – or IC-IMPACTS for short. Based on UBC’s Vancouver campus, the initiative tackles pressing social problems through solutions that involve research collaborations between India and Canada, and helps build trade linkages between the two countries. Banthia’s self‑repairing concrete is one such collaboration.

“Development always meant a lot to me. Coming from a very poor community in India – with no water, no infrastructure – I think those are the things that stick with you,” says Banthia, who speaks thoughtfully in precise sentences. He became an engineer in the hope that he could make a difference, studying structural engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi before beginning doctoral studies at UBC in the 1980s.

When the federal government put out a call for an India‑Canada research centre, Banthia consulted Canadian and Indian researchers and companies to develop IC‑IMPACTS’ vision to tackle social challenges common to both countries. Banthia won the funding for UBC to build a centre, in partnership with the University of Alberta and the University of Toronto, with a mission to “develop and implement community-based solutions to the most urgent needs of each nation: poor water quality, unsafe and unsustainable infrastructure, and poor health from water-borne and infectious diseases.”

Canada and India may seem worlds apart on measures related to GDP, climate and poverty, but Banthia saw what he called an “obvious” connection between the challenges facing his native and adopted countries. He draws parallels between the more than 100 First Nations communities facing boiled water advisories and the tens of millions of Indians who lack access to safe drinking water. He also recalls the De La Concorde Bridge that collapsed in Montreal in 2006, killing five people and injuring six others.

Canada and India may seem worlds apart on measures related to GDP, climate and poverty, but Banthia saw what he called an “obvious” connection between the challenges facing his native and adopted countries.

“We [Canadians] need these new materials – crack-healing materials,” explains Banthia. “As much as we need it in Thondebhavi, we need it in Montreal too.”

All IC-IMPACTS projects are carried out with dollar-for-dollar funding from Canada and India. Technologies are jointly developed and rolled out by researchers and companies from both countries. They work closely with people in communities like Thondebhavi, where the local village council was consulted and ultimately gave permission to IC-IMPACTS to build the road. Other IC-IMPACTS’ collaborations include efforts to develop and install low-cost water treatment systems for communities in remote parts of Canada and India. For example, a UBC professor is leading a project to develop technology that uses bacteria and gravity to clean water. Researchers are also working on improving infrastructure and public health. One such initiative aims to increase early detection of tuberculosis in one of India’s poorest states. Another is focused on developing a portable tool for detecting eye infections.

But Banthia’s horizons are bigger than the immediate problems these projects tackle: he wants to shape how Canada does trade. IC-IMPACTS can spur industrial partnerships that increase trade between Canada and India, as well as Canada and other emerging economies, he explains. Plans are already underway to bring Mexico and China into the fold.

“In the end, we are moving towards developing technologies for the global economy,” says Banthia. For this, international collaboration that helps researchers develop technology attuned to the conditions of different countries, including their geography and culture, is key. “When you co‑develop technologies,” he explains, “you are coming up with very elegant solutions that are appropriate for a country as opposed to developing technologies without quite understanding a country, without quite understanding the regulations, without understanding the process, the people, their expertise, conditions [or] culture.”

The concrete project highlights the value of this model. The self-healing technology was developed by Banthia at UBC, but the road in Thondebhavi was designed and built in partnership with the National Institute of Engineering in Mysore and the University of Alberta, as well as Indian and Canadian companies. ACC Cement, one of the largest cement companies in India and a partner on the project, helped identify Thondebhavi – which is just over two kilometres from one of its cement factories – as a site for deploying the technology. Now, researchers are observing how the road, which has three different segments of varying thickness and proportion of materials, performs in a tropical environment. A second road is slated for the Lubicon First Nation north of Edmonton to examine how the concrete performs under extreme cold.

Banthia’s horizons are bigger than the immediate problems these projects tackle: he wants to shape how Canada does trade. IC‑IMPACTS can spur industrial partnerships that increase trade between Canada and India, as well as Canada and other emerging economies, he explains. Plans are already underway to bring Mexico and China into the fold.

If the self-repairing concrete takes off, it could be a big business. Forty-six per cent of roads, amounting to three million kilometres, are unpaved in India, while nearly one million kilometres of roads are needed in remote parts of Canada, according to IC-IMPACTS. And those numbers don’t include roads being built in emerging economies like China, and the new buildings and bridges that inevitably come with them.

For now, the concrete will be used for two more projects in India: a two‑kilometre road in Haryana and the replacement of a five-kilometre stretch of highway in Madhya Pradesh. Even so, a decade or more could pass before the technology is widely adopted. Even though Banthia’s innovation is an improvement on regular concrete that could result in significant savings, governments may be reluctant to adopt it widely for years, says Shashank Bishnoi, a concrete expert at the Indian Institute of Technology in New Delhi. First, they’ll want to see proof of the successful performance of multiple roads made with the special concrete, he explained. That could take as much as a decade, possibly more.

For villagers in Thondebhavi, the self-repairing road is a source of pride and curiosity. The whole village turned up to see the new road being built in 2015, recalls Basavaraju Balootagi, a government officer who has been managing local infrastructure development for five years. He proudly shows off a photo album filled with pictures of foreign visitors, including Banthia.

When the villagers saw tiny nail-like fibres being mixed with chemicals, they grew suspicious, continues Balootagi, sitting in his office in a government building on the outskirts of Thondebhavi. Curious passers-by peer in through the grills on the windows as he recounts the construction of the road. “People began to ask whether, in future, these things would rise up and cause the tires of motorcycles or bicycles to puncture.”

That was far from the case. “These things” were actually steel fibers that were added to the concrete to improve the strength of the road. The mixture also contains special nanocoated fibres that attract water and are one of the key elements of Banthia’s concrete. When concrete reinforced with these nanocoated fibers cracks, it can repair itself with a small amount of water, which could come from rainfall or another external source. The water hydrates the cement at the site of the crack, resulting in a chemical reaction that bonds the road by reproducing the same product that gave the concrete its original strength. The technology works in all kinds of climates, though a long draught soon after casting would be an issue, Banthia says.

“There are fibres in this concrete that are keeping the crack narrow and, as the crack is formed, they bond. It’s like a stitch,” explains Banthia, placing his palms together, then pulling his fingers apart before interlocking them, as he describes the mechanism. “Then, as the water comes in, they produce additional products that now fill the crack that has just formed.”

The road in Thondebhavi is also a model for environmentally friendly construction. The mixture makes use of fly ash, a by‑product of coal plants that would otherwise go to waste, while the high strength of the concrete makes it possible to use less cement.

The road in Thondebhavi is also a model for environmentally friendly construction. The mixture makes use of fly ash, a by-product of coal plants that would otherwise go to waste, while the high strength of the concrete makes it possible to use less cement. In fact, the road is 60 per cent thinner than a typical Indian road, and its embedded sensors indicate it has held up in the face of heavy rains and extreme heat. Most Indian roads fall apart within five years, with many “showing deterioration within two years of being laid due to poor materials, intense heat, poor drainage, and monsoons,” according to a write-up about the project by IC-IMPACTS. In contrast, Banthia anticipates the road in Thondebhavi will last as long as 15 years before needing maintenance, describing it as a demonstration project for low‑cost, long‑lasting, climate-friendly roads for rural and remote areas.

Banthia’s technology offers great possibilities, and yet the concrete road in Thondebhavi looks just like any other. For the locals, it’s the everyday benefits of the road built by IC-IMPACTS and the government‑funded road accompanying it that matter most.

The old road running past their houses was in such bad shape that some villagers dreaded leaving their homes. One woman describes it as having been unbearable, while a middle-aged farmer complains of getting boils from walking in filthy, stagnant water on the road. “We had to wash our feet with soap water every time, but an itching sensation remained,” he says.

There were also economic costs, as locals struggled to take their produce to market. “The new road is smooth,” says Suresh Reddy, a farmer who grows tomatoes and maize. “Earlier it was bumpy. And the tomatoes would bang about in the boxes and get squashed. You get lesser prices because of this.”

Cows would defecate on the old road, adding to the muck when the road became waterlogged with monsoons. “Now, nobody allows anybody to dirty the road,” says Yashodamma of the village council, noting that the elimination of such filthy water means that fewer worms, snakes and malaria-transmitting mosquitos are attracted to the area. “Earlier no one gave a damn.”

As for Banthia, such everyday changes are one of the most “satisfying” parts of his career. His face lights up when he talks about meeting a man using a wheelchair during a visit to Thondebhavi. “[The man] said, ‘Thank you so much for building this for us, because, during the monsoon months, this whole village is completely unwalkable. There is no way you can walk around, let alone [use] a wheelchair. … Now, I can go visit my family. I can go visit my friends,’” recalled Banthia.

“This was the most exciting thing. When he came and said thank you.”

Writer Alia Dharssi travelled to Thondebhavi this summer. She interviewed the villagers and government officials, who all speak the local language Kannada, with the help of a translator.