Courage, Education & Hope

Sipping hot chai tea from a glass cup in the principal’s office of a primary school in Kabul, Afghanistan, Lauryn Oates’s outer calm conceals a simmering frustration. Thousands of dollars in donor money from Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan (CW4WAfghan) to fund construction of a new school is in limbo. This year, a plot of land was bought from Kabul’s municipal government to relocate the school. CW4WAfghan had contributed $50,000 to build the new facility. But a powerful local chieftain, upset that a school for 235 poor children was to be erected in his district, scuttled the project. Oates and the principal discuss what to do. “We should get rid of that land and get the money back,” says Oates, who is dressed in a headscarf, tunic and long skirt down to her ankles.

The principal, clean shaven, bespectacled and wearing a grey business jacket, says through Oates’s translator that the purchase is under government review and it is not possible to get the money back. The translator looks at Oates and assures her in English that it will be possible to secure their investment, but gently chastises her, “you should have gotten the support of the people there.” However, the fault does not lie with Oates; an overeager school director approved the purchase of land but neglected to consult with the local chieftain. “This is heart-breaking,” says Oates.

“Building schools is not what CW4WAfghan is all about,” says Oates. “A school can be a sheet strung between two trees. It is a school only when it has teachers and curricula.”

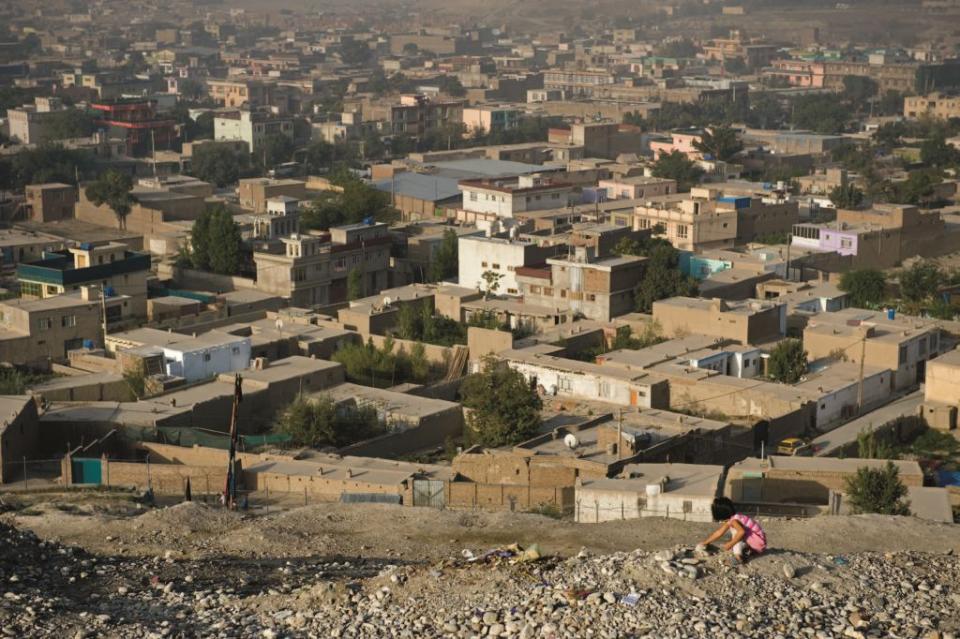

“Development is messy,” she says later with dry understatement. And development in Afghanistan is especially chaotic, requiring deep reserves of patience and ingenuity to cope with conservative, misogynous tribal traditions, political corruption and the daily logistical nightmare of navigating dusty, rutted streets patrolled by heavily armed police. It certainly isn’t the end of the world that the school won’t have a new facility in the next year or so, because a source of money has been found to pay the high rent at the current location. “Building schools is not what CW4WAfghan is all about,” says Oates. “A school can be a sheet strung between two trees. It is a school only when it has teachers and curricula.”

Oates graduates with a PhD in language and literacy education from UBC this November. As CW4WAfghan’s projects director in Afghanistan since 2008, she has broadened and strengthened the 16-year-old NGO’s mandate in Afghanistan to spread literacy and life skills to a largely uneducated populace of children, youth and women. The organization also focuses on training the nation’s teachers – many of whom haven’t finished high school – and donates 500-book library kits and comprehensive science kits valued at $1,500 each to communities, villages and schools. The work is carried out either as donor-funded projects or in partnership with other NGOs and government ministries. The results are impressive. So far, CW4WAfghan has graduated 4,000 Afghan teachers from its programs and puts 50,000 girls through school every year.

The school may be run down, but there is a small revolution going on inside. Unlike most primary schools in Afghanistan, all the teachers have bachelor degrees.

Despite the recent misadventure in capital investment, the school is a dynamic success story. It was started by Aid for Afghan Women and Children, one of CW4WAfghan’s many NGO partners, to educate and support orphans and the children of destitute families. Unfortunately, the school has moved three times in the past two years due to soaring rents. The current building is decrepit, with cracked walls and floors and dirty windows in warped frames, thin cherry-red classroom carpets for the children to sit on (there are no chairs or desks) and walls painted Pepto-Bismol pink. Although some schools in Afghanistan have playgrounds, usually the result of foreign aid, this particular school has no swings, slides or teeter-totters. If money were invested in a playground, the landlord would capitalize on the improvement and jack up the rent. “So we don’t want to invest any money in the facility,” says Oates. Yet the investments that have been made are valuable beyond measure. The school also has a small medical clinic staffed by volunteer nurses and doctors to provide health care to students and their families. From 20 to 50 people every day use the clinic, which has been supported in part by the Boomer’s Trust Fund, a Comox, BC-based organization honouring the memory of Cpl. Andrew “Boomer” Eykelenboom, who was killed in Afghanistan in 2006 by a suicide bomber. Boomer’s Trust also pays for school uniforms and supplies, and the organization has agreed to pay a year’s rent.

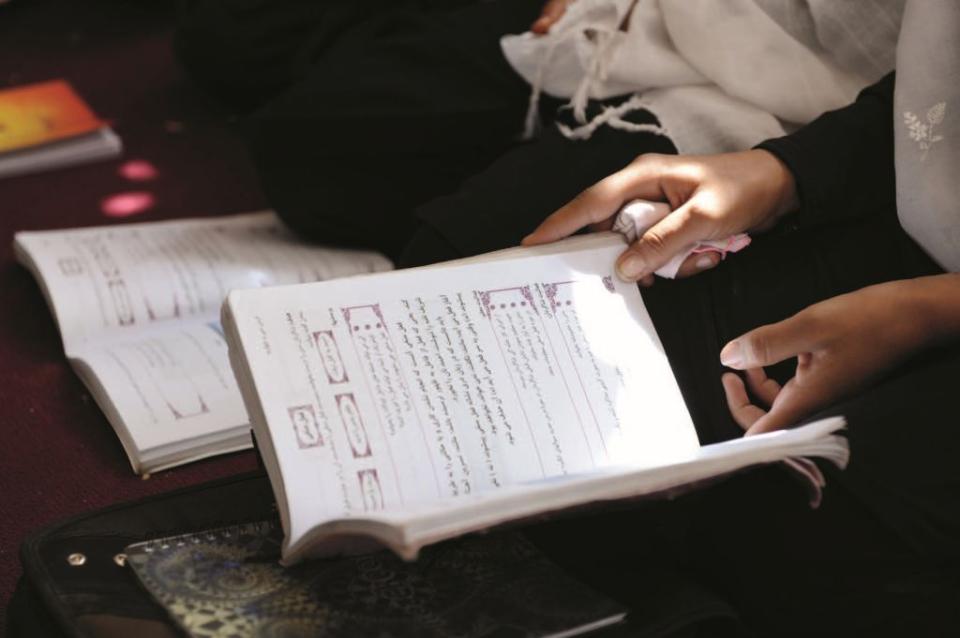

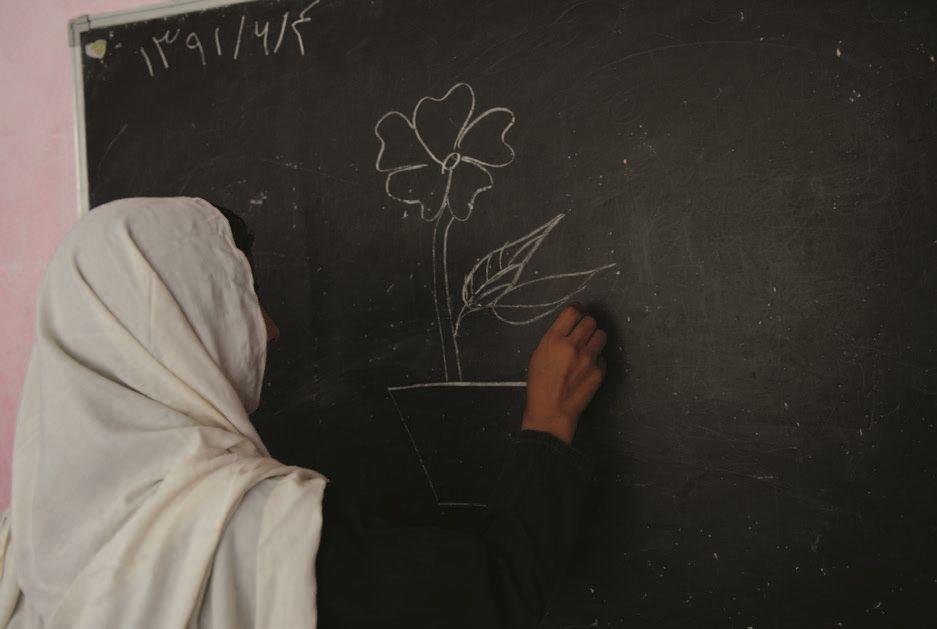

The school may be run down, but there is a small revolution going on inside. Unlike most primary schools in Afghanistan, all the teachers have bachelor degrees. Unfortunately, a solid academic grounding doesn’t guarantee survival in Afghanistan, so the boys are also taught mechanics and the girls tailoring. Girls and boys receive instruction in the same classrooms – an anomaly in a nation where the tradition of purdah – segregating males from females – means separate gender-based schools. (Girls’ schools generally get the short shrift when it comes to books and resources like lab equipment, Oates says.) Here, the boys, dressed neatly in black pants or jeans and t-shirts, sit on one side of the room. The girls, prim in white hijab headscarves edged with lace, black or green tunics and loose pants, sit on the other side. Girls express their individuality on their hands, which are covered in delicate henna calligraphy or vibrant red nail polish. The students proudly read from English textbooks, while another class sings a dirge in Dari remembering the orphans left behind during the Soviet Union invasion of the 1980s. One tiny girl, with huge bags of stress and fatigue under feral eyes, clings mutely to a taller student during the song. The pain contained in that one little body doesn’t go unnoticed by Oates, who says that many of the students, all from desperately poor families, sometimes endure unspeakable things. “Some kids have terrible circumstances at home, or terrible things have happened in the past,” Oates says.

One 15-year-old girl, who is in Grade 7, stands up to read a passage of poetry. Dressed in head-to-toe black, she has a noble carriage, with huge crystalline eyes sparkling with intelligence. Every day, she walks 13 kilometres to and from school. When not in class, she adds to the family income by making and selling naan, the leavened, oven-baked flatbread that is a staple in Afghanistan. The girl says she wants to be a doctor when she grows up. Given opportunity and support, the determination in her eyes leaves no doubt she can achieve her goal.

There are important lessons to be learned for NGOs and government donors, says Oates. Opening a school “doesn’t mean anything.” What’s important is the quality of the education, which requires long-term investment by NGO donors. “We’re often too focused on the physical outputs of aid and development when we have to be focused on the human outputs. It’s what goes on in the school that counts.” Oates addressed this issue in her doctoral study, which analyzed the development of mother tongue teaching resources in primary schools in Uganda using information communications technologies such as computers. “Despite all this money being spent on equipping computer labs and sending computers to Uganda, at the end of the day they didn’t make sure that people knew how to use them,” says Oates, who was twice given the Social Science & Humanities Research Council award during her academic career. “You can’t just give someone something – they have to be fully capable of manipulating that thing that you gave them. It’s the same here in Afghanistan – just 30 per cent of women with primary school-level education can actually read and write, so why bother sending kids to school?”

Oates believes that literacy is key to helping this war-wracked nation achieve permanent stability and security, gender equality and rule of law. Statistics show that “countries most likely to be at war are those with the worst education systems.” Literacy and its foot soldiers – well-trained, committed teachers – transcend religious, gender and cultural divides, becoming an antidote to violence, extremism and poverty while nurturing Afghan civil society. Eyeing the social, economic, legal, health and political disaster left by a generation of warmongering mujahedeen guerrillas and Taliban Islamic fundamentalists, Afghan youth have rejected the old ambitions of “wanting to be warlords,” Oates says. Now, they aspire to become engineers, teachers, doctors, nurses and police officers – professions achievable only through education.

Overriding these lofty ambitions is the spectre of Taliban insurgents, who circle Kabul like a school of sharks, keeping its five million inhabitants in a constant state of dread with suicide bomber attacks. The US and NATO forces that drove out the Taliban in 2001 are hurriedly training Afghan nationals to replace them in time for the planned withdrawal of foreign troops in 2014. “All this money has gone into training police and army to provide security for the country,” says Oates. “They equip them with uniforms and guns. But at the end of the day, if the police see a suspicious vehicle, they can’t read the license plate or write it down.” Literacy and education changes the way that a police officer thinks about himself, says Oates. “They take pride in their work. Illiterate police ask for bribes and they are mean to citizens; they are thugs in uniform. A literate police officer is much more professional. Literacy has to be part of the training.”

Literacy and its foot soldiers – well-trained, committed teachers – transcend religious, gender and cultural divides, becoming an antidote to violence, extremism and poverty

There is no higher purpose for literacy and education in Afghanistan than the elevation of the status of women, a key predictor of a nation’s stability, says Oates. The appalling treatment of women under the Taliban first connected Oates to Afghanistan in 1996 when she was only 14. Newspaper reports detailing the murder, whipping, beating, jailing and torture of citizens sparked a rage in the young teen that has never abated. In 2008, Oates co-authored a study laying bare the extent of violence against women in Afghanistan. Funded by Global Rights Partners for Justice and titled Living with Violence: A National Report on Domestic Abuse in Afghanistan, the study found that 87 per cent of women in Afghanistan had experienced physical, sexual, or psychological violence. Sixty two per cent of women endured multiple forms of violence, 17 per cent reported sexual violence and 11 per cent rape. Forty per cent of women had been hit by their husband in the past year, while 74 per cent suffered psychological abuse. Another 60 per cent of women were in forced marriages. The reality, says Oates, is that Afghan women endure torture and are murdered with impunity. They are beaten and raped for such “crimes” as over-salting the family meal. They have scalding hot water or acid thrown in their face. One abuse victim, 18-year-old Bibi Aisha, was featured on the cover of Time in 2010 after her Taliban husband chopped off her nose and ears to punish her for running away from home. Others women are victims of so-called honour killings – when a man kills a female relative to restore the family’s tarnished reputation. Such slayings are just an excuse to get rid of “a woman you don’t want,” Oates says.

CW4WAfghan’s teacher training program is bringing enlightenment to deeply conservative communities throughout Afghanistan where mullahs, or religious leaders, uphold interpretations of Sharia law and the Qur’an that denigrate women. Teaching women’s rights requires subtlety. Gender differences are minimized in science classes, where students learn that males and females are of equal intelligence and have a physiology that is more similar than different. They learn that cultural mores that license the abuse of females is wrong and punishable by law. Educated girls grow up knowing that they don’t have to tolerate violence. They aspire to careers outside the home and, as a result, have fewer children. Education gives them skills that allow them to contribute to the family income, creating homes that are healthier, happier and more prosperous, Oates says.

It is the end of a long day, and a crepuscular sun dangles above the horizon, a dull burnt orange in the haze of choking pollution. But the day isn’t finished; Oates has a long night of work ahead of her at CW4WAfghan’s office in a downtown neighbourhood of Kabul. To many, Afghanistan’s future is as dim and uncertain as this inky darkness of gathering night. But for Oates, a glow illuminates the way forward – the light of hope and determination from the school’s young pupils, from women like herself, and from the other courageous women and girls of Afghanistan.