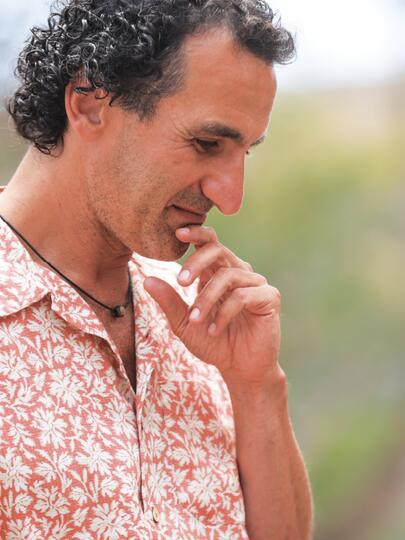

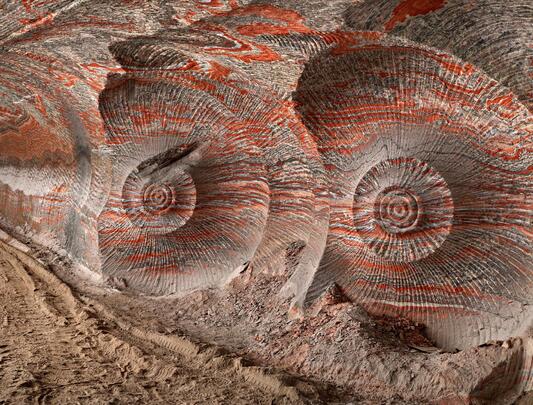

Illustration by Gracia Lam

How to talk about climate change

Facts alone are not enough. If we want to engage everyone in climate action, we need psychological strategies.

This is where we are in the climate emergency. The data is in. The facts are incontrovertible. There’s no denying that we’re in a crisis of our own making. We (in the Global North particularly) consume too much and waste too much, and unless we pivot en masse to more sustainable energy choices – quickly, and definitively – our very survival as a species is on the line.

And yet knowing all this hasn’t lit the needed fire under the majority of us. Rational argument may be the wrong tool for the job of solving this dilemma. Emotion is our best bet. But some emotions are more effective than others.

“Shame and guilt are the worst,” says Jiaying Zhao, a UBC cognitive scientist and Canada Research Chair in Behavioural Sustainability. Indeed, those go-to psychological levers of the environmental movement may backfire. “Negative emotions don’t motivate people to change. They just make us retreat further into ourselves.”

There’s a better way to make folks pivot green, Zhao discovered. Her “aha moment” came at the end of a faculty meeting, when her colleague, psychologist Elizabeth Dunn, approached her with the million‑dollar question: “Can we make climate action feel happy instead of miserable?”

Zhao answered in a heartbeat: “Of course!” From behavioural science, she knew that people need to feel excited and empowered before they will willingly course‑correct in any lasting way. But she’d never rigorously applied that insight in this domain.

Zhao – who likes to geek out on calculating how much carbon certain activities produce – drew a circle on a page. Inside it she listed the top things we can do to “substantially reduce greenhouse-gas emissions.” Dunn did the same, only in her circle she wrote the actions with the largest happiness benefits (her bailiwick). The two researchers put their circles together. There, in the sweet spot in the middle, was the gold: actions that not only reduce emissions but make you feel happier at the same time.

They began to cook up interventions they could test.

Back at home, Zhao opened her refrigerator. She knew a key component of reducing emissions is reducing food waste. It occurred to her that out-of-sight-out-of-mind food is the first to rot. So she re‑organized the fridge, with the perishables up front, and the more shelf‑stable stuff in the back. “I feng‑shui‑ed my fridge!” she says. “I haven’t wasted any food since!” Nor is she fishing icky moldy stuff out of the crispers. This makes her immoderately happy.

Dunn is a world expert in the benefits of “talking to strangers,” so it’s not surprising that a lot of the eco behaviours she thought of have a social dimension to them. Like getting people out of their cars and into the knack and smack of city life, on foot or on bicycles. Human connection goes up. And human connection makes us happy.

(This insight dovetails nicely with what UBC economist John Helliwell has found in his own work. Helliwell studies the degree to which urban design interventions that make cities greener also, in the bargain, tend to lift the spirits of city‑dwellers by putting them in the path of one another. When it comes to what makes us happy with our life, “relationships with other people trump everything else – yes, even income,” he says.)

Parker Muzzerall, a PhD candidate in sociology, discovered there is one negative emotion that can be effectively leveraged for pro-environmental behavior change: worry. In one study, Muzzerall and colleagues found that the folks who were most concerned about the climate emergency were also most likely to support a transition to renewables. Anxiety is itself a kind of energy, you could say – a state of discomfort people are motivated to relieve by doing something. Deed makes creed.

It turns out that adopting energy‑saving habits – like washing your clothes in cold water, or unplugging appliances when they aren’t in use – often requires very little personal sacrifice. They’re actually a net‑positive because it feels good to be part of the solution. It’s empowering to really grasp the idea that small changes by individuals actually matter – a lot. For many, a natural next step is to dial up our city officials and make our voice heard.

“That’s what they’re there for,” Zhao says. “We can tell them what we want. Like, we want EV chargers. We want more urban green space. We want more bike lanes. We can demand these things.” Airing your dreams to the people in charge can have a ripple effect. “In my department we set up a climate action committee,” Zhao says. “What happens is, you generate FOMO. Other departments want in on the party!” In some ways this is the key bridging personal and governmental responsibility: it’s a call for individuals to march without letting governments off the hook.

Over at UBC’s education faculty, Derek Gladwin has been doing his own work on mucking with human motivational machinery in the shadow of the climate emergency. An associate professor of language and literacy – and also a member of the Clean Energy Research Centre – Gladwin has a kind of magic icebreaker he uses with his students and in workshops with educators. It’s a question that beguiles and engages in a way that simply asking folks “What are you doing to fight climate change?” does not. The question is: “What’s your energy story?” The beauty is that everyone has one.

“Here’s mine,” says Naoko Ellis, a professor of chemical engineering who with Gladwin co‑runs the Systems Beings Lab at UBC. “When I became a mother, I started thinking about energy differently. Personal energy – we have a finite amount of that. So with a new child I had to ask, Where’s my energy going now? The question is no longer What do I need? but What does this family need? What does this system need?” Our personal energy stories become entry points into the larger narrative of planetary sustainability. We can conclude that, despite what Hollywood insists – with its stories of heroism, of saviourism, triumphalism – this rodeo is not actually about me. It’s a surprisingly empowering mental swerve. “I no longer feel like it’s on me to show the way forward,” Gladwin says. “It’s on us.” And that’s a collective responsibility.

UBC sociologist Emily Huddart has found that many of the current eco messages are preaching to the choir. That is, they’re reaching a group she calls The Eco-Engaged. These folks are one of the five personality types she has identified – along with The Optimist (who doubts the problem is as bad as all that), The Fatalist (we’re done for, so why bother getting out of bed?), The Self‑Effacing (who cares but doubts they can have much impact), and The Indifferent (kind of meh on the whole thing). The Engaged are already on board. The real work now is to persuade the other four to join the club.

If we’re going to get out of this predicament alive, environmental groups need to make their pitch land with everyone – not just those who are half‑way sold already. That means tailoring stories to the mindset of who you’re trying to reach – by foregrounding the part of the message they’re paying attention to (a phenomenon called “motivated attention”).

If we’re going to get out of this predicament alive, environmental groups need to make their pitch land with everyone – not just those who are half‑way sold already.

In 2018, Zhao and colleagues published a study involving two groups of test subjects: liberals and conservatives. Each group was shown a graph of rising global temperatures – “the sturdiest piece of evidence for global climate change,” Zhao says. By tracking people’s eye movements as they viewed the graph, “we showed that liberals and conservatives pay attention to this temperature curve very differently, and that has consequences for how they behave.” Liberals looked more at the steep hockey‑stick uptick, but conservatives cast their eyes back along the timeline. Maybe this current spike is a fluke; it’s not due to human activity at all, but just part of a natural cycle. For that story to be true, you just need to go back far enough. “We look for information that confirms our existing beliefs,” Zhao says. Effective messaging for conservatives might anticipate their skepticism and address that off the hop.

The takeaway here is that everyone is looking at a slightly different part of the elephant, and thereby coming away with a different understanding of what the elephant is. The fix, then, is to spin the elephant. To expose people to a side they haven’t seen... in a way that’s non‑threatening.

A few years ago the BBC hatched an ingenious documentary called “Human Power Station” (part of its Bang Goes the Theory series) to drive home just how much energy the average family uses in a day. What if we had to produce that energy ourselves? A guinea‑pig family was recruited to occupy a house for one weekend and just, well … do what they normally do. Unbeknownst to them, all the power to the house was being supplied by a couple dozen cyclists recruited from local gyms, churning away behind the wall, as required. (“Oh no, Mom’s putting the roast back in the oven. Pedal harder!”) An unforgettable “energy story” was loosed into the world. It’s impossible to have seen it and continue to use energy at the same wastrel levels as before. The documentary does what writer Rainer Maria Rilke said all art must. It sends a message: “You must change your life.”