The delinquent

When an overzealous 1930s student administration treated him unfairly, Louis Chodat claimed the moral victory, and then some.

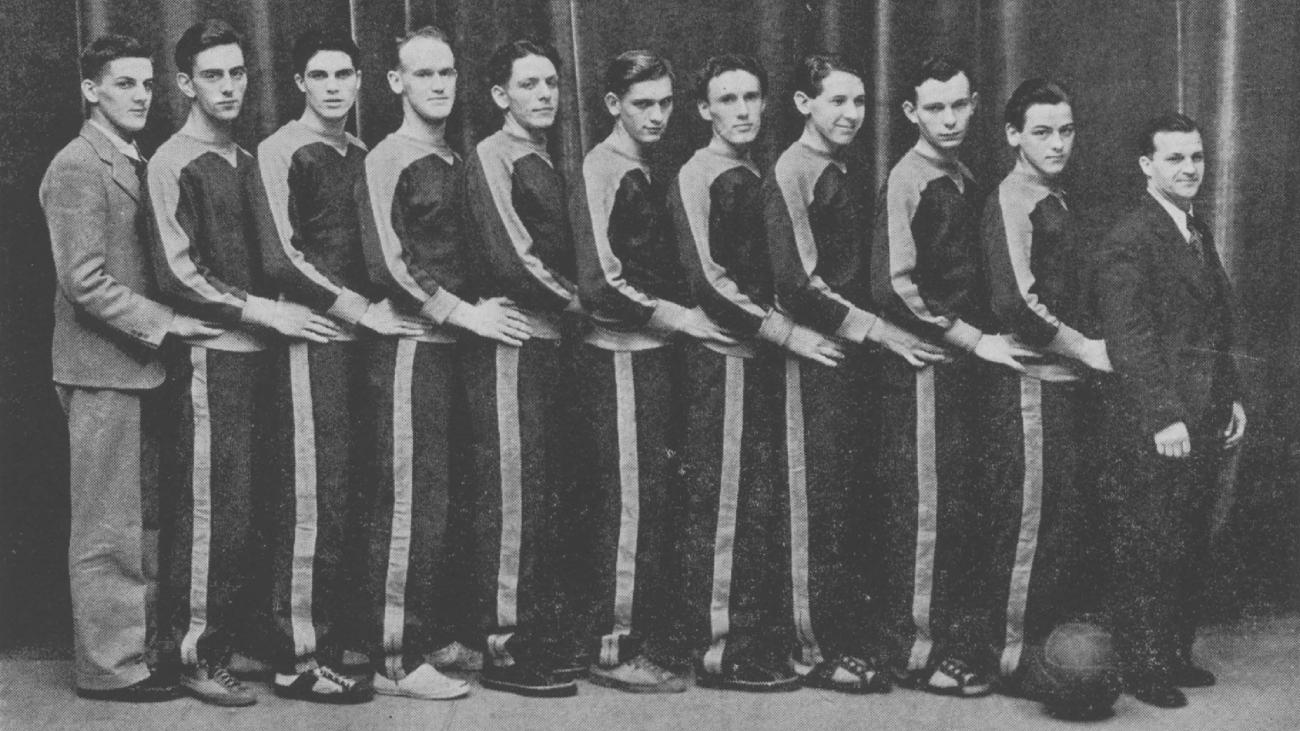

Poor Louis Chodat. The son of an admired UBC French professor, he might have been expected to excel at university. And he did, though not in the classroom, where one might expect, but on the playing fields. He became a star athlete when he arrived on campus in 1930, playing both basketball and “Canadian rugby,” which was not rugby at all, but the newer game of North American football. He was good at throwing forward passes and kicking converts and field goals. His offhand remarks were treated as witticisms, and he was soon to display a strong streak of loyalty, though not in a way that endeared him to Student Council.

It was in his second year that he ran into difficulties. He hadn’t completed his first year’s studies, and so began to be declared ineligible for certain games. This was treated in a light-hearted way at first in a basketball game between “Eligibles” and “Ineligibles,” but things got more serious in the spring of 1932 when Council discovered that young Louis was playing for non-UBC teams. It seems his heart was much more in athletics than academics, and if he wasn’t going to be allowed to compete as a UBC player, well then he would sign up for teams at the YMCA or the Vancouver Athletic Club or Ryerson United Church.

No, no, no, said Council. It’s against Alma Mater Society policy for UBC students to play for outside teams. Long before this The Ubyssey had railed against UBC athletes who played for outside teams, especially if they played against UBC. It is “childish and petty,” the paper said in 1924, “and, further, it is disloyal.” Council in 1932 took the same approach, warning Chodat to stop playing for the Y. Chodat said he would have to consult his teammates at the Y: a sign of loyalty, one might think, but the wrong sort of loyalty. Council fined him $5 (about $95 in today’s money).

Chodat refused to pay. Council took the case to the university administration, which agreed to issue a one-day suspension. The Ubyssey declared this a glorious moment. True, the bulk of the student body were on the side of the “delinquent” — and who wouldn’t be? He was not being allowed to play for UBC, and then was fined for playing for others. But The Ubyssey thought there was an important principle to uphold: the power of Student Council, the right of the Alma Mater Society to enforce its own rules, even if it created a little hardship for an individual student.

It is “childish and petty.”

The Ubyssey’s take on student athletes who played for non-UBC teams (1924).

The case made the papers outside UBC. The Vancouver Sun made him out to be a hero and said he came out the winner because he paid the fine and then was allowed to play for the Y. Not sure that really made him the winner. In any case, in the next few years Chodat continued to appear in the sports pages of The Ubyssey as a star player, but for outside teams playing against UBC. This raised no new issues because by that time he had left the university.

He went on to join the air force and in 1940 married Stella Brinham. He died in 1978. He never finished his degree, the academic side of the Chodat inheritance being left to his sister Isabelle, who did complete a degree (in nursing) and even won a $15 prize on graduating in 1936. She went on to marry William Petrie, a physicist who also wrote a book on orchids.

As to the rule against playing for outside teams, that was finally abolished in 1949 by a general meeting of the student body after Student Council once again tried to fine a “delinquent” athlete for playing for an outside team. Louis Chodat would have been pleased, one likes to think.

Sheldon Goldfarb is the archivist for the Alma Mater Society. For more tales of UBC student life, see his book, The Hundred-Year Trek.