A Running Start

It’s just past 8:30 on a warm Thursday morning and the clubfoot clinic at Old Mulago Hospital in Kampala, Uganda, thrums with activity. Rows of bright orange plastic chairs are filling up with babies and their parents. The atmosphere is positive and calm. Behind a blue-curtained divider a mother undresses her baby. To their left, an open doorway faces onto the treatment room. Sounds of cooing and a few cries of protest emanate as plaster casts are gently soaked in warm water, tiny feet massaged, new casts applied, and braces fitted.

Three-month-old Allan Martin has been brought to the clinic by his parents. He was born with bilateral clubfoot, meaning both his feet are turned inward and downward. Left untreated, they would continue to twist as he grows until eventually the sensitive tops of his feet would become the part he walks on, and walking would be painful, if not impossible. Allan breastfeeds contentedly, unperturbed by the lightweight yet clunky casts on each of his legs and oblivious to the growing number of people milling about. Within a few weeks Allan’s feet will look close to normal and he’ll no longer need the plaster casts. Instead, he’ll be fitted with a brace – essentially a pair of open-toed shoes affixed to a rigid metal bar – to be worn constantly for three months and then, for about four years, just while sleeping. Allan’s parents are relieved that their son is receiving this simple yet revolutionary treatment known as the Ponseti method.

Each year, approximately 1,600 babies are born in Uganda with clubfoot deformity. Until recently, they had scant hope for a cure. Most would go undiagnosed until the crippling disorder had robbed them, physically and emotionally, of any expectations for a normal existence. They faced a future without school, without a job, without the opportunity to marry and raise a family. Being born with clubfoot deformity was a life sentence of poverty and pain.

Prior to 1999, those few who were diagnosed early enough were treated with surgery or with a nonsurgical technique called the Kite method. The biggest difficulty with clubfoot surgery is the scar tissue that develops during the healing process and results in painfully stiff ankles. Besides, the cost of surgery is prohibitive in developing countries. For 40 years the nonsurgical Kite method prevailed by default as the treatment of choice in Uganda, despite an abysmal 10 per cent success rate.

Now, thanks to the passionate dedication and groundbreaking work of Shafique Pirani, a clinical orthopaedics professor at UBC, the superior Ponseti method has supplanted the Kite method, and the outlook for babies like Allan – not only in Uganda but all over the world – is extremely positive. Earlier this year, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons recognized Dr. Pirani’s achievement when they unanimously declared him the winner of their 2012 Humanitarian of the Year Award. The Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America soon followed suit.

“Feelings drive actions,” he says. “These actions really come from a deep feeling of injustice on behalf of these kids. I can’t run, so I want to give these little kids the opportunity to run.”

Pirani was born in Uganda, the fifth of six children. At age three he was stricken with polio, and to this day he walks with a limp, uses a cane to get around, and tilts forward slightly when standing. Living with the effects of polio has driven this warm and gracious man to do everything in his power to cure people suffering from clubfoot deformity. He knows first-hand how hard life can be growing up with a crippling disability, how it feels when kids hurl cruel nicknames at those who look different. “Feelings drive actions,” he says. “These actions really come from a deep feeling of injustice on behalf of these kids. I can’t run, so I want to give these little kids the opportunity to run.”

In a way, Pirani was lucky. When he contracted polio, he was treated at Mulago Hospital’s Round Table Polio Clinic founded by Dr. Ronald Huckstep, the hospital’s first professor of surgery. After personally attending young Pirani for almost three years, Huckstep referred him to England for foot surgery. “We were passed up the chain until we met Dr. Austen, who was himself a polio victim who walked with crutches,” recalls Pirani. “He examined me and said to my mom, ‘Your son will make a fine orthopaedic surgeon.’ And of course, you know, for my mom that was an instruction.”

Pirani stayed in England for school, always returning to his beloved Uganda on the long holidays. Then, on August 9, 1972, when Pirani was 15 years old, his world once again turned upside down. Without warning, Ugandan dictator Idi Amin decreed that the country’s 80,000 citizens of Asian ethnicity had to leave within 90 days. Although Pirani was third-generation Ugandan, he was also an ethnic Asian. His parents were anxious to protect their children and wasted no time: a few days after Amin’s announcement, the Pirani family boarded a plane to England with whatever they could fit in their suitcases. They were forced to leave behind the rest of their belongings.

To the young Pirani it seemed at first like a holiday, until the family began walking across the tarmac to the waiting plane. Then he felt a deep sadness. “As we got to the stairs I thought to myself, ‘This may be the last time, ever, that my foot is going to be on Ugandan ground.’ And I remember that feeling going up with me on the stairs.”

The family relocated to Vancouver after a brief stay in England, but Pirani never forgot Dr. Austen’s “instruction.” He returned to England where he completed a medical degree. Then he did a residency in orthopaedics at UBC, followed by a fellowship in paediatric orthopaedics at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. While there, Pirani was exposed to clubfoot surgery. He knew immediately that treating clubfoot deformity was his calling. Finding no common yardstick for measuring and comparing the degree of deformity in clubfoot, he set about devising his own rating scale, now called the Pirani Clubfoot Severity Score, which has become the universal standard. In the course of developing this scale, Pirani acquired rare and vital insights into clubfoot anatomy.

In 1991, Pirani established a private practice and joined UBC’s Department of Orthopaedics. As his practice grew, he became increasingly engaged in the problem of clubfoot, not only in its treatment but also in its teaching and research. One day, he stumbled upon a book called Congenital Clubfoot: Fundamentals of Treatment by Dr. Ignacio Ponseti, who claimed phenomenal success with a treatment method of his devising that he had used for 40 years. If this was such an effective method, Pirani wondered, why wasn’t everyone using it? What he learned was that most doctors who had tried the method had met with failure. They didn’t properly understand it, Pirani says, but their lack of success gave the Ponseti method a bad rap causing the rest of the medical community to ignore it. Fortunately, the expertise that Pirani had acquired while developing his clubfoot rating scale equipped him with the insight to appreciate Ponseti’s method and the skills to implement it.

Meanwhile, things were changing yet again in Uganda. Idi Amin was ousted and banished from Uganda. When Yoweri Museveni was elected president, he invited the expelled Asians to return. The Pirani family yearned to see their old home once again and, in 1998, a trip was arranged.

While preparing for the trip, Pirani responded to “a little one-paragraph thing” in the Canadian Orthopaedics Association newsletter. It was a note from Dr. Norgrove Penny – who has since joined UBC’s Faculty of Medicine – saying he was in Uganda and, “if anybody’s travelling through, give me a buzz.” The ensuing conversation opened up a whole new chapter in the history of paediatric orthopaedics.

I said, “Wow, Norgrove, you should do the Ponseti method.’ After a pregnant pause of a few seconds he said, ‘No, Shafique, you should do the Ponseti method.’ And that was the turning point.”

Sitting down to breakfast with Penny in Kampala’s Sheraton Hotel, Pirani talked about being the lone Canadian using the Ponseti method and Penny described his spectrum of practice in Uganda. A volunteer at Mulago Hospital, Penny was performing about 200 surgeries a year to correct neglected clubfoot deformity. “He expressed his frustration and concerns because he didn’t know whether he was doing the right thing,” says Pirani. “He just knew that there were all these children that were terribly disabled, physically and emotionally, and he had to do something about it… I said, ‘Wow, Norgrove, you should do the Ponseti method.’ After a pregnant pause of a few seconds he said, ‘No, Shafique, you should do the Ponseti method.’ And that was the turning point.”

For the next six months, they strategized – Pirani in Canada, Penny in Uganda – to solve Uganda’s problem of neglected clubfoot. The obstacles were significant and the questions many. How could babies and young children be diagnosed? Who would determine their treatment plans? An estimated 10,000 Ugandans were suffering from neglected clubfoot, and Pirani dreamed of introducing an intervention to the entire country! Uganda’s population is the same as Canada’s, but while Canada boasted almost 1,000 orthopaedic surgeons, Uganda had only eight. Most of those lived in Kampala, where they focused not on birth defects but on trauma cases.

Then Pirani had an epiphany. In Uganda, a cadre of paramedical personnel called orthopaedic officers are specially trained in the non-operative management of orthopaedic ailments. They work under the direct supervision of medical officers and surgeons throughout Uganda. Surely, Pirani thought, they could be trained to manage the Ponseti method. It could be integrated into their basic curriculum, building capacity for a sustainable clubfoot treatment program.

Pirani and Penny shared this plan with the stakeholders in Uganda, including the Ministry of Health and Makerere University’s Department of Orthopaedics. They received unanimous approval, and Pirani enlisted the Rotary clubs of Burnaby, New Westminster Royal, and Kampala for financial support.

This was long before the Ponseti method had gained acceptance by the medical profession. Thus, when a draft of the plan landed on Ponseti’s desk at the University of Iowa, with Pirani and Penny’s request that he review it, Ponseti was flabbergasted. For decades he’d dreamed of seeing his technique adopted but, aside from his team and Pirani, there were only three successful practitioners in the world. Although the scale of the proposed program was two individuals doing humanitarian work, Ponseti was struck by the support offered for his method by multiple levels of healthcare and coming from, of all places, far-off Uganda.

In late 2002, with the Uganda clubfoot training program nearly complete, Pirani and Penny surveyed the results. They found disappointing news: some of the spaces earmarked for clubfoot clinics had never been made available; many parents lived too far to commute for treatments; some hospital administrators had sequestered their clubfoot staff to other departments. Still, the successes where the method was embraced were sufficient to spur Pirani on. He knew it was essential to establish ongoing training and a comprehensive public health approach, and this would cost money.

In partnership with Makerere University and Uganda’s Ministry of Health, Pirani guided UBC through a multi-phased competition held by the Canadian International Development Agency. In 2004, CIDA awarded UBC nearly $1M, and the Uganda Sustainable Clubfoot Care Project was born. Contributions from UBC, Makerere University, and other partners increased the project value to $1.8M. Pirani was appointed as the project director and Edward Naddumba, a professor at Makerere and senior consultant orthopaedic surgeon at Mulago, was appointed the Ugandan co-director.

With 40 well-functioning clinics located strategically throughout Uganda, thousands of children have already been cured – 1,100 in the past year alone – and the Ponseti method is firmly entrenched in the country’s healthcare and higher education systems.

As the success of the Ponseti method in Africa became known, doctors throughout the western world embraced the method. The World Health Organization now promotes it as the universal gold standard for clubfoot treatment and recommends that developing nations model their clubfoot care programs on the Uganda program. Pirani has helped establish similar care programs in Malawi, Kenya and Tanzania and is currently developing massive programs in South Africa and Bangladesh.

The Uganda program’s capacity-building mandate concludes at the end of this year and Pirani will step down as director, leaving future governance to Uganda’s Ministry of Health. “When we went to Uganda,” he says, “we really wanted to do ourselves out of a job, and we have.”

Receiving 20 to 25 babies each Monday and Thursday, the Clubfoot Clinic at Old Mulago Hospital – located in the very space where Pirani was treated for polio more than 50 years ago – is believed to be the busiest such clinic in the world. Dominating one wall of its treatment room is a large poster explaining the pioneering work of Pirani and Penny. This morning, senior orthopaedic officer Diriisa Kitemagwa is seated at a wide folding table. His quick eyes take in everything that’s going on. He knows all the returning patients by name, and it’s his task to determine the next step in each small patient’s recovery program.

Hassan Manzi has brought his three-year-old son, Aksam, for a routine checkup. Aksam has been attending the clinic since he was five days old. After five weeks of casting, he had a tenotomy – snipping of the Achilles tendon so it could lengthen – followed by one last cast, and then bracing. He didn’t like wearing the brace at first, but before long he didn’t even notice it.

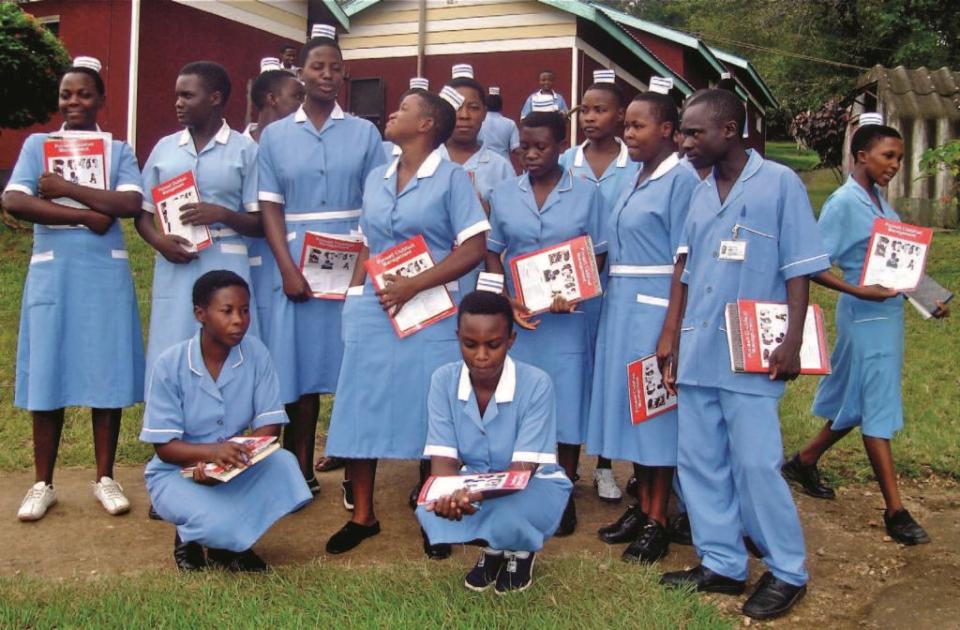

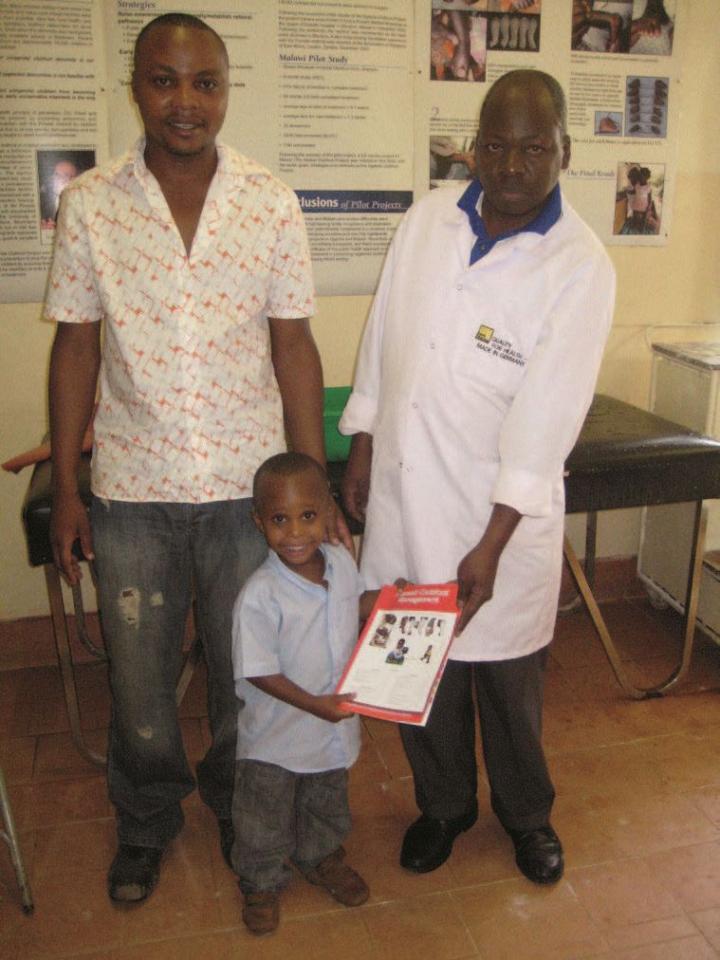

Today, Aksam discovers, it’s a special occasion. “His feet are well,” announces Kitemagwa, clearly pleased. Although Aksam will continue to wear a precautionary brace each night for another year, he no longer shows any signs of clubfoot. Kitemagwa celebrates by giving the young patient a slim red book, Ponseti Clubfoot Management, a compilation of articles contributed by Pirani and many Ugandan medical experts.

“I’m giving Aksam the red book, talking about clubfoot and treatment, as a first book in his library,” says Kitemagwa, and Aksam beams up at him. “When he starts reading, he should read about clubfoot, and maybe grow up and do medicine and become an orthopaedic surgeon.” And perhaps one day little Aksam will come to regard this gentle encouragement as an instruction.

In 1972, article contributor Rosemary Anderson took time out from her studies at UBC and taught high school in Uganda. She vividly recalls the turmoil and fear of those days and made her first trip back to the country in 2012.