A family connection to the Klondike

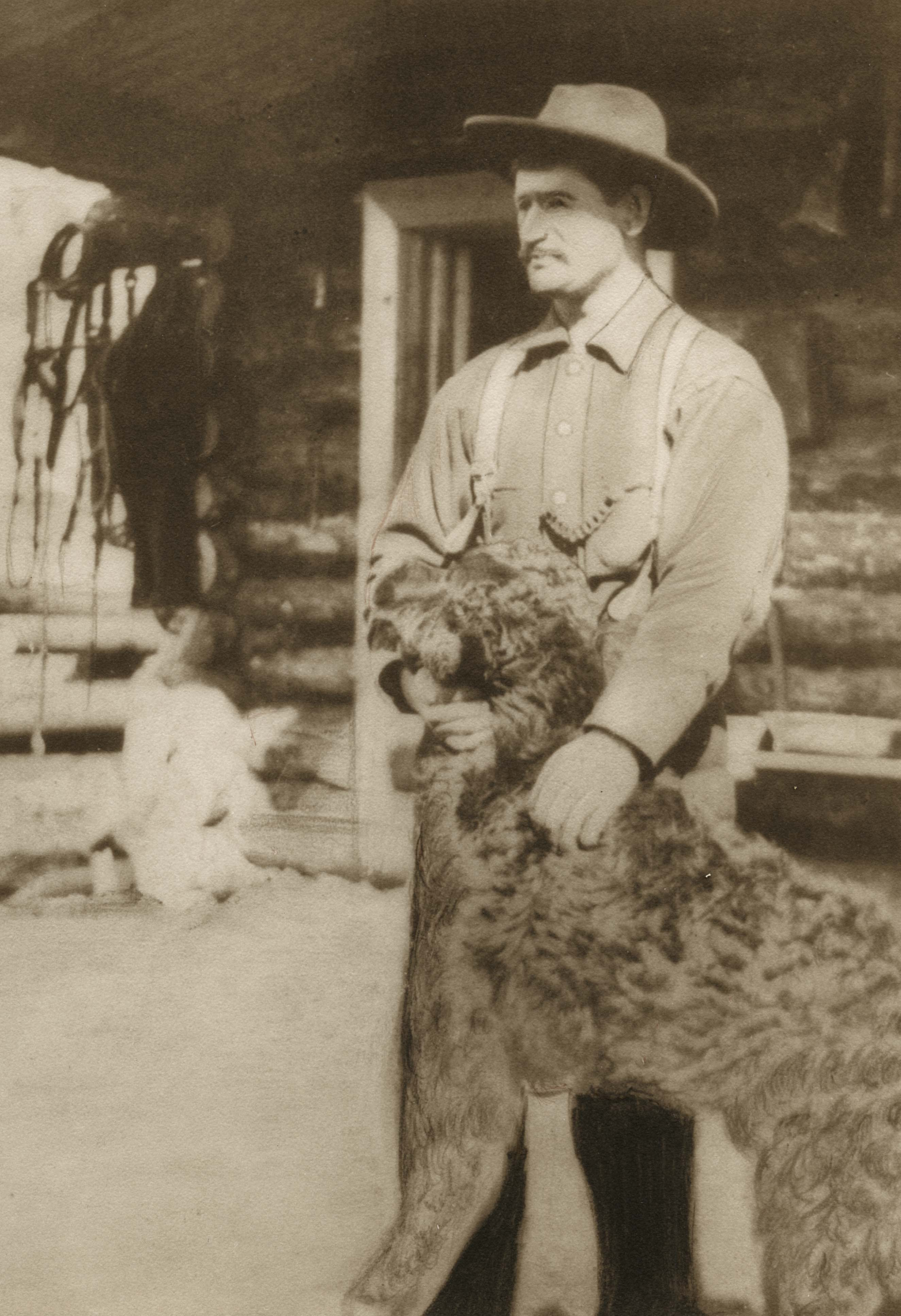

John Grieve Lind — my grandfather — a railroader-turned-prospector from London, Ontario, was already up north looking for gold when the big strike occurred in August 1896.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-1250

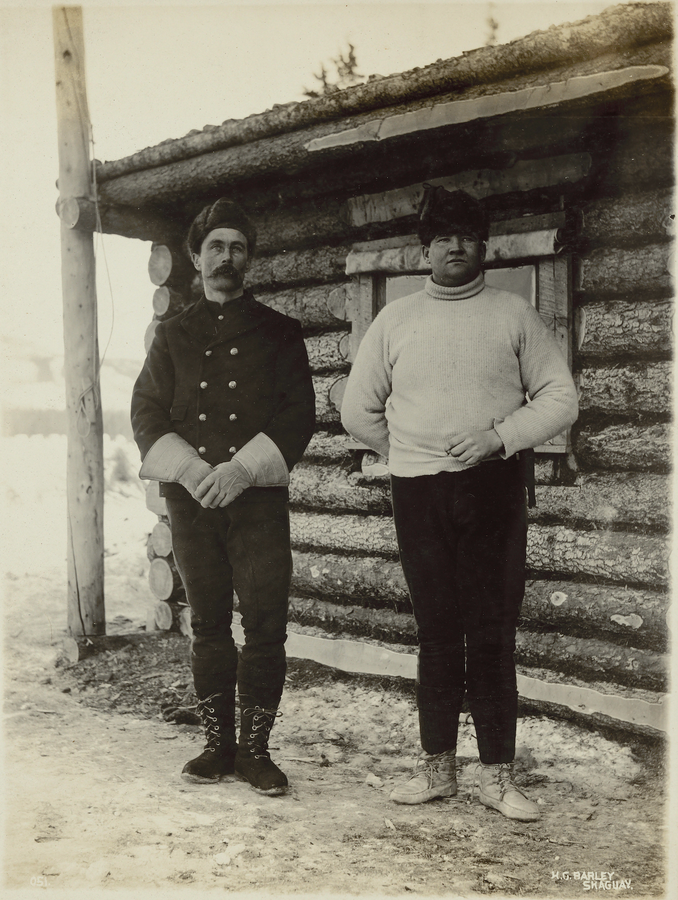

The stampede north

When news of the gold rush broke, first in San Francisco and Seattle in 1897, thousands rushed to the North in search of fortune and adventure. On arrival, they faced arduous winter conditions.

This is the famous Chilkoot Pass summit in 1898.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-0801

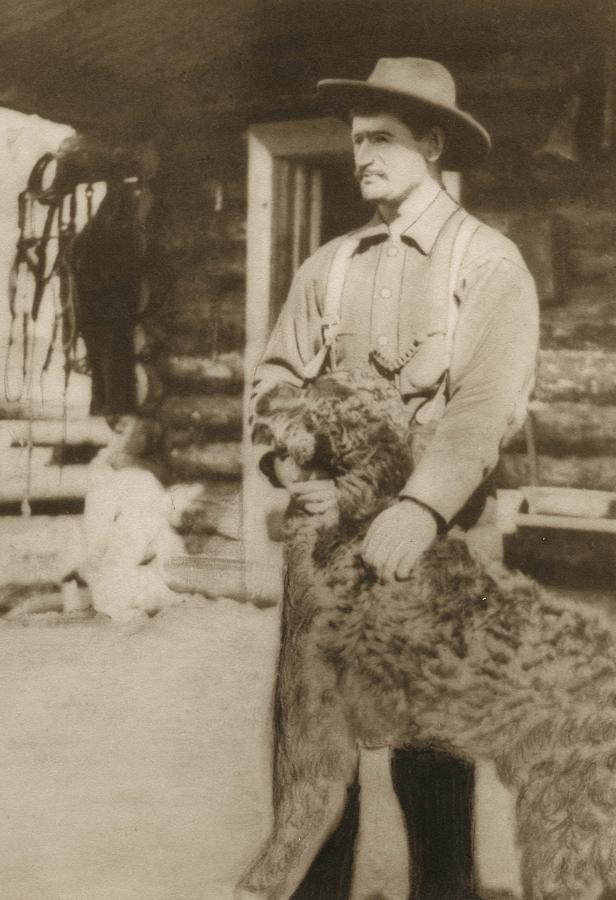

Becoming a “Sourdough”

The miners’ nickname “Sourdough” dates back to 1849 California because sourdough was the main bread eaten during that gold rush. Later, in Alaska and Yukon, a miner became known as a Sourdough only after spending at least one full year in the North and surviving the winter.

Photo credit: UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-0237

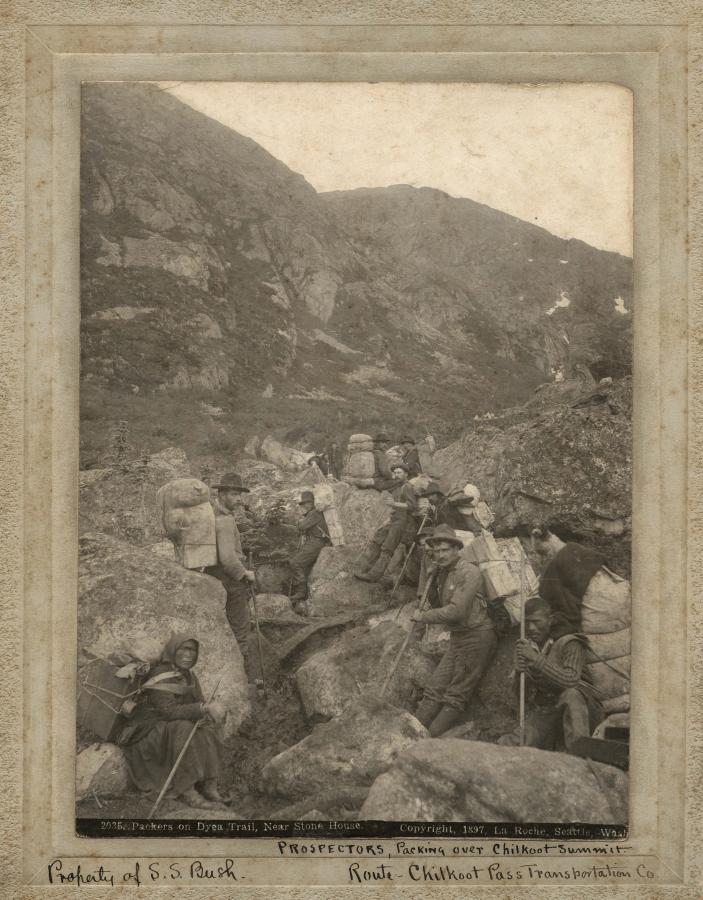

The impact of the gold rush on Indigenous peoples

From time immemorial, Indigenous peoples had been living in the Klondike and surrounding areas. The gold rush affected many Indigenous communities, encompassing over twenty language groups, along the Yukon River and its vast drainage basin. Only over time is the wider world coming to understand the impact of the gold rush on the lives, land, and culture of the Indigenous peoples in this part of Alaska and the Yukon, as well as recognizing the significant roles they played.

Here, prospectors are packing over the Chilkoot summit route, 1897. Miners relied heavily on Tlingit and Tagish packers to carry their provisions over the rugged Coast Mountains.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-1255

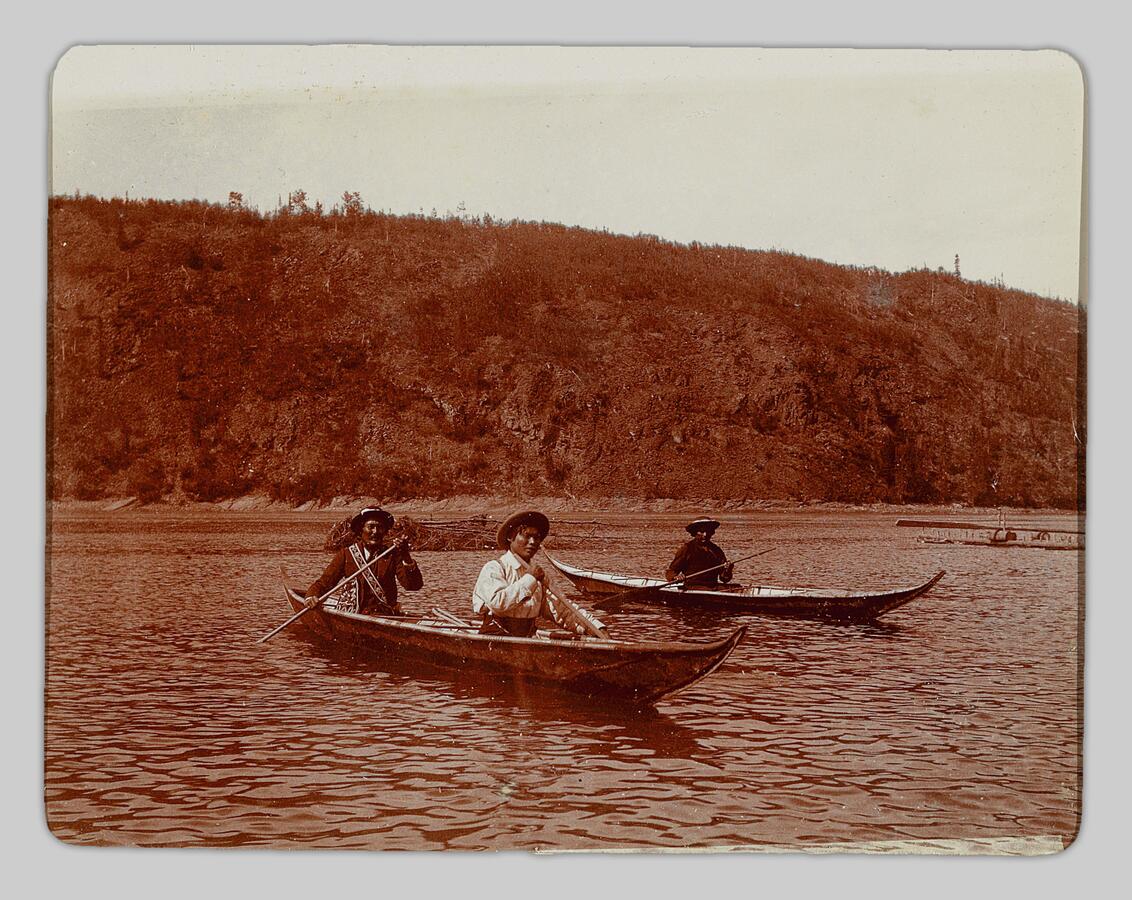

The aftermath of the gold rush

Three men on canoes, 1897.

For millennia, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in have lived along the middle Yukon River. When stampeders arrived, they anglicized the name of the Tr’ondëk River as “Klondike” and occupied Tr’ochëk, a fishing camp, to build Dawson City.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people survived the onslaught of the gold rush and the sudden, severe colonial experience it created, and they now work to educate settlers about how to properly live on this land today.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-0764

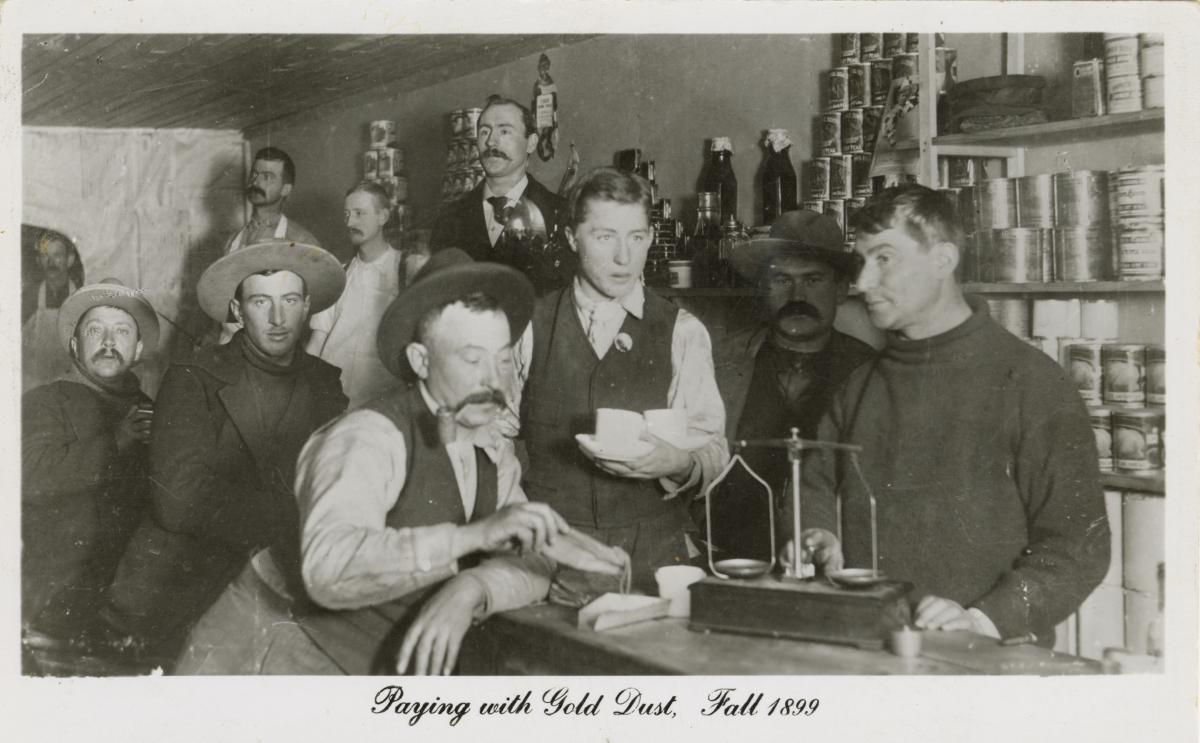

Fortunes made and lost

Thousands flocked to the Klondike with dreams of wealth. A few hundred struck it rich, but many squandered their earnings in saloons and gambling halls.

This detail of a postcard is from Dawson City in 1898.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-11-43-08

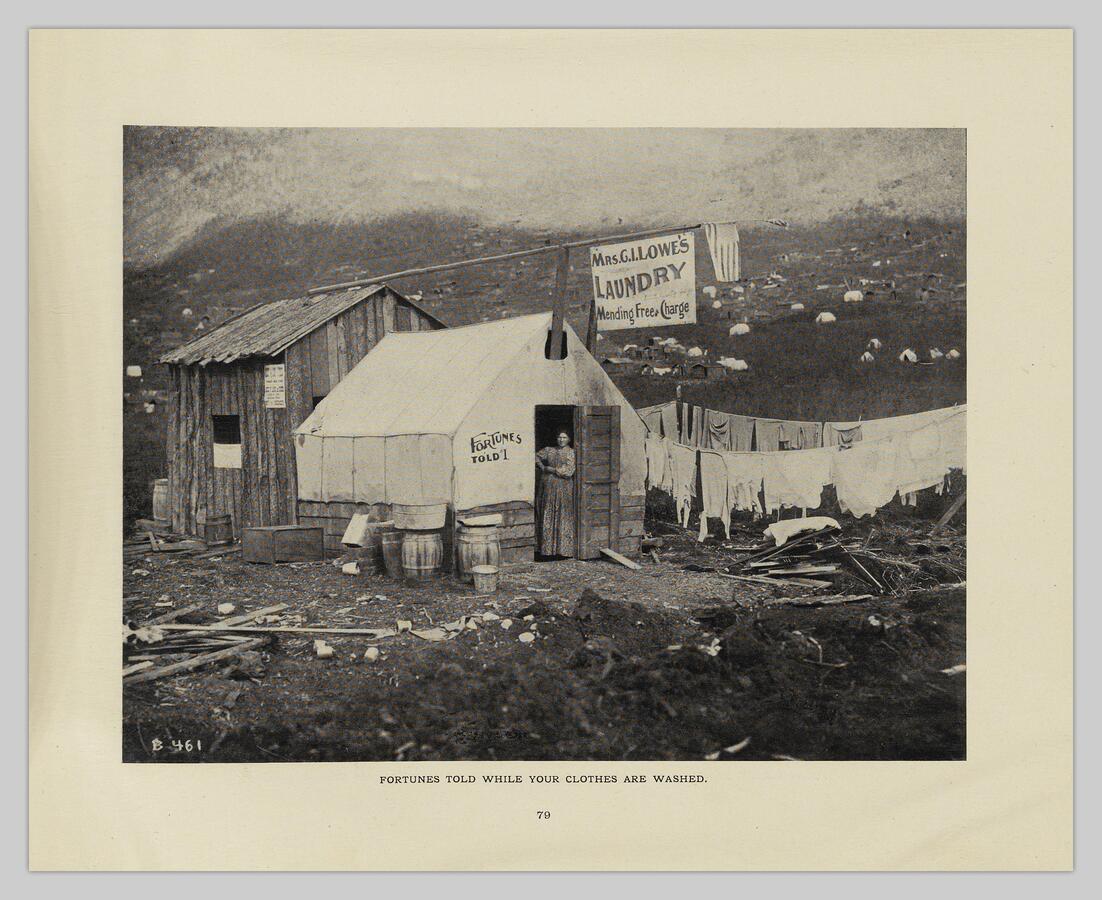

The extraordinary women of the Klondike

A laundress looks out from the doorway of her tent where miners and others could have their shirts laundered and their futures foretold.

The Klondike of the 1890s was a male-dominated world, with an estimated 5% of the population of stampeders being women.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-21-10-PAGE-79

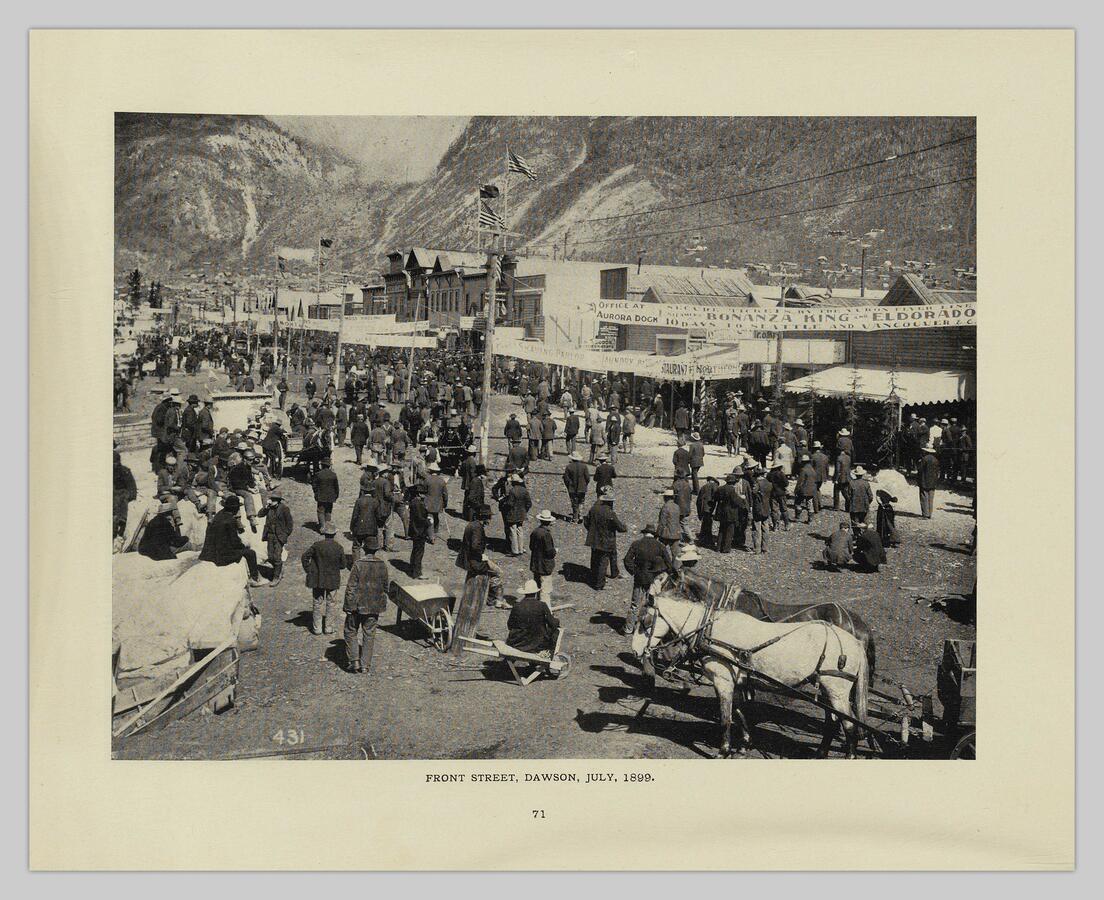

The rise and fall of Dawson City

In a matter of a few short years, between 1896 and 1899, Dawson City’s population exploded to around 17,000 — and shrunk to about 8,000 after the rush ended.

This is Front Street in July of 1899.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-21-10-PAGE-71

Life in Dawson City

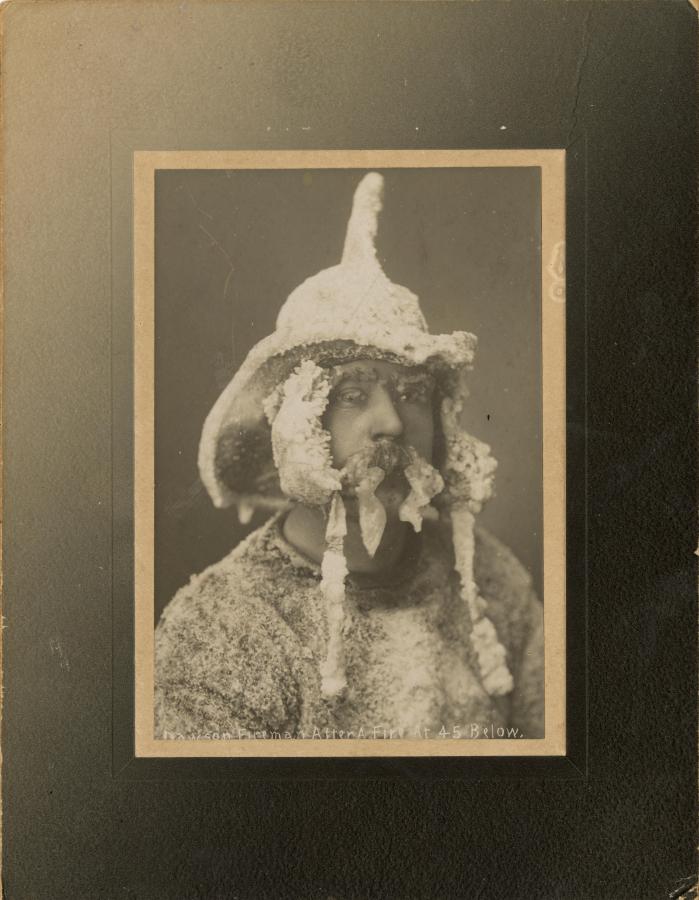

Fire was the greatest threat to Dawson City. The city was made of wood and canvas and was built in a hurry. Its buildings, cabins, and tents were heated with primitive wood stoves, and they were lit by candles and coal oil lamps. Together, these were a recipe for disaster, and fires regularly broke out.

This photograph is of a fireman after the huge Dawson City fire of April 26, 1899, when temperatures dropped to -45C.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-1655

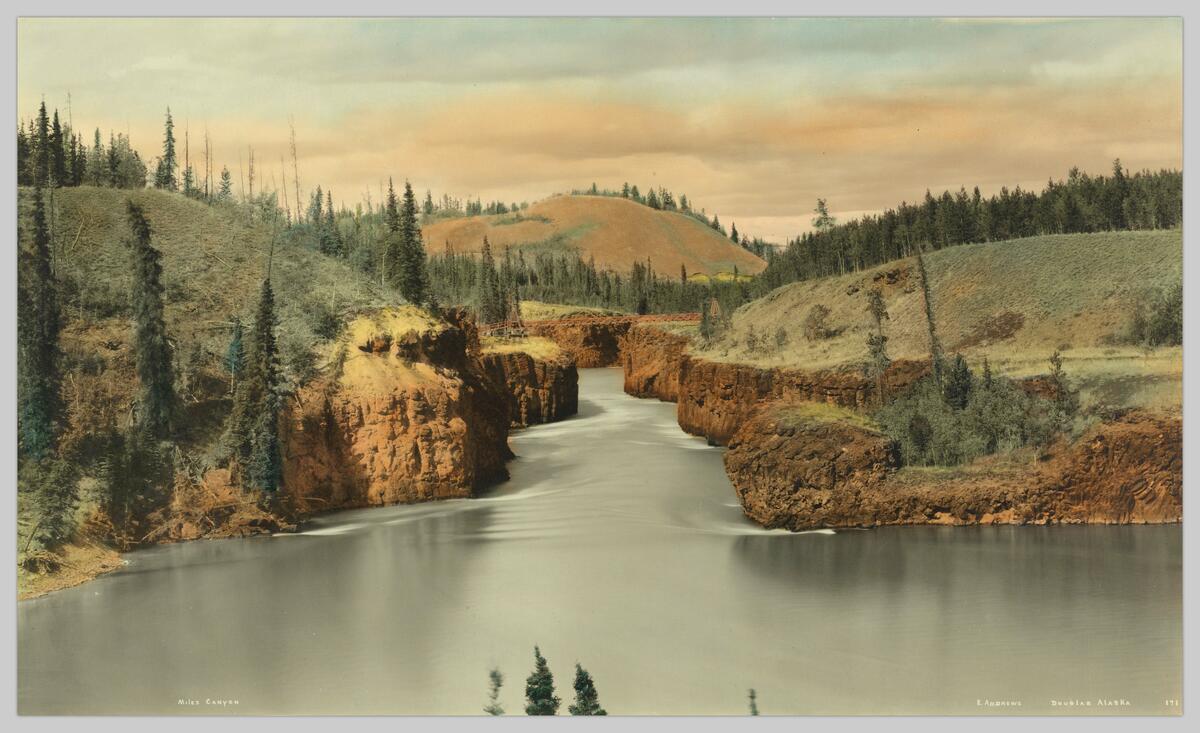

Building a collection over 50 years

Inspired and coaxed by my father, Jed, my grandfather’s second son, about 50 years ago I began collecting anything involving the Klondike era. My collection grew into thousands of pieces and has been designated “a cultural property of outstanding significance” by the federal government’s Department of Canadian Heritage. It is my pleasure to donate the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection to my alma mater, the University of British Columbia, to share with researchers and the public at large.

Detail of a photograph depicting Miles Canyon in Douglas, Alaska, between 1900 and 1920.

UBC Library, The Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection, RBSC-ARC-1820-PH-1789

Learn more

Tales of an Unsung Sourdough is available anywhere books are sold. In collaboration with my co-author Robert Brehl, I share my grandfather Johnny Lind's fascinating story, the history of the gold rush, the colourful players in that famed period, and the peoples and land affected by the legendary stampede for wealth.

Learn more about the Phil Lind Klondike Gold Rush Collection.

Editor’s note: Philip B. Lind passed away on August 20, 2023. Read this tribute to Lind by UBC Interim President and Vice-Chancellor Deborah Buszard.