Illustration by Klawe Rzeczy

Birthright citizenship is a basis for equality

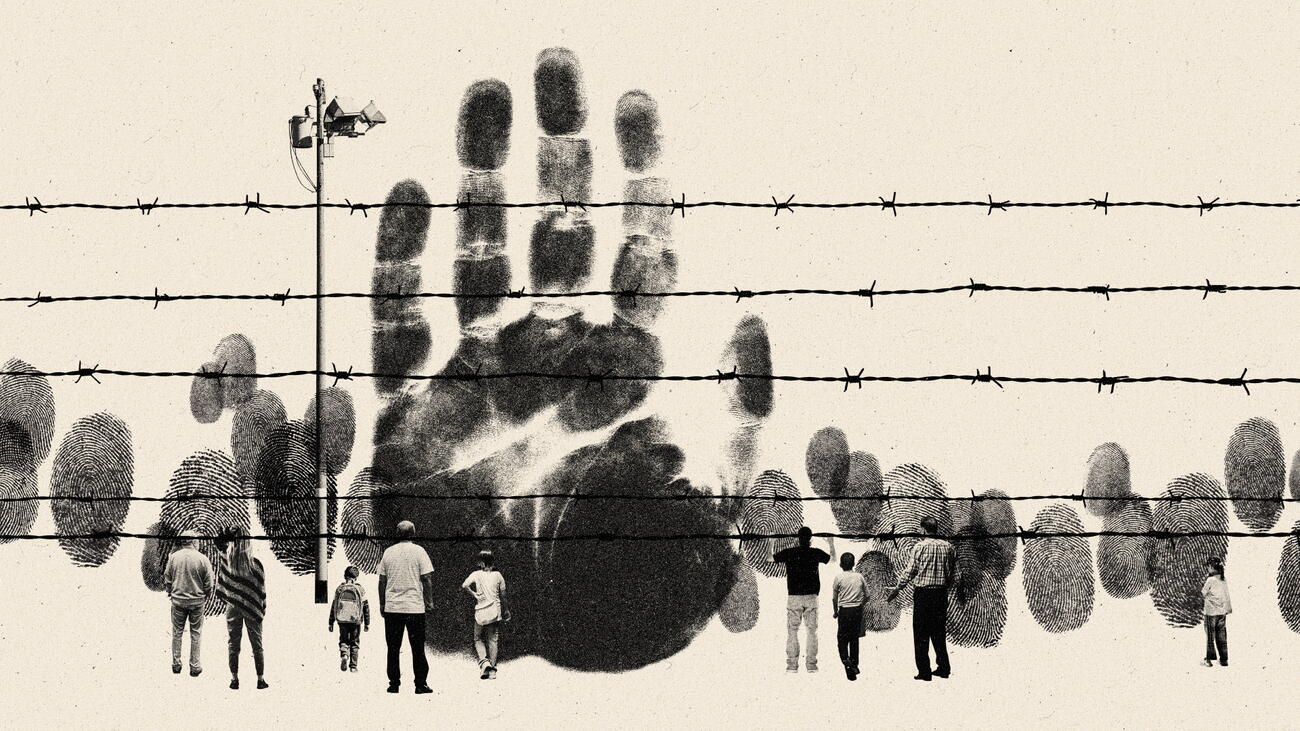

Dismantling it risks turning democracy into a gated community, say UBC experts.

The term is jus soli – “right of the soil.” Commonly known as birthright citizenship, it is essentially a licence to inhabit whatever random spot in the world the universe sees fit to drop you and call it home.

Historically, the concept of a nation was defined by its predominant ethnicity, and citizenship largely determined by one’s family bloodline: jus sanguinis, or “right of blood.” But over the past century, as modern transportation has brought every border within reach and our growing capacity for international conflict has displaced people by the millions, emigration from one’s home country has become more common, and most nations have come to embrace a combination of dirt and blood in defining who can call their lands home soil.

In the US, the roots of birthright citizenship run old and deep, enshrined in the Constitution’s 14th Amendment, passed shortly after the American Civil War to ensure equal protection for formerly enslaved peoples. Canada similarly prides itself on the inalienable right of citizenship for those born to its shores, but the legal ground is shakier than most Canadians realize – protected by law, but subject to the whims of the party in power.

Although widespread in the Americas, broadly inclusive birthright citizenship is rare in Asia and Africa, and has recently been pared back in Australia and across Europe. The notion that a person has a right to live where they are born is a simple idea that has become warped by the realities of globalization, and increasingly subject to conditions such as parents’ legal status. As immigration surges and national identities grow more fractured and diverse, birthright citizenship is seen by some not as a guarantee of equality, but as a loophole to be closed. For others, it remains an integral pillar of democracy.

“It’s extremely important that countries of immigration like Canada and the United States have birthright citizenship based on territory because it is a way of levelling the playing field in each generation,” says Irene Bloemraad, professor in the departments of Sociology and Political Science and co-director of the UBC Centre for Migration Studies. “Especially for immigration countries where there’s such diversity in our immigrants in terms of religion, background, language, skin colour, etc., it provides one basis of equality, given all of the ‘othering’ that can happen. It’s an incredibly equalizing law and ethos.”

“Us” and “them”

It is the “othering” that dominates the conversation around birthright citizenship today. Immigrants looking for a better life have become a right-wing boogeyman, particularly in the US, reshaping the concept of birthright citizenship from a shield to a cudgel. Terms like “anchor babies” and “birth tourism” have turned a unifying principle into a divisive one: yes, you are a citizen, but you do not belong.

“Territorial birthright citizenship is absolutely in peril, globally speaking,” says Amanda Cheong (BA’12), assistant professor in the UBC Department of Sociology and author of the forthcoming book, Omitted Lives, on exclusions from civil registration and citizenship. “Canada and the USA are among just over 30 countries today that grant unrestricted jus soli, and since 2000, countries like New Zealand, Ireland, and most recently the Dominican Republic, have abandoned unrestricted jus soli. This is a concern because Canada and the USA have been facing similar anti-immigrant political pressures to follow suit.”

With colleagues at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa, Cheong is currently working under a major grant funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to debunk the stereotypes surrounding birth tourism in Canada, where opponents of birthright citizenship are stoking a panic to justify adding more barriers to becoming a Canadian.

“What we’re finding in our research is that these political narratives are not only inaccurate, but harmful to immigrants and racialized minorities in our society,” says Cheong. “This is dangerous because political arguments that birth tourism is on the rise – or that birth tourism is posing a substantial threat to the sanctity of the institution of birthright citizenship in Canada – is based on either no data, or flawed, imprecise, and incomplete data and estimation methods, which are fundamentally incapable of identifying migrants’ actual motivations for migrating to Canada and giving birth on Canadian soil.”

Weaponizing the very concept of birthright citizenship to create an imaginary underclass of natural-born citizens can have a chilling effect on a democracy. Both American and Canadian histories are littered with race-based attacks on the institution of belonging: Canada’s Chinese head tax of 1885; the internment of Japanese Canadians and Japanese Americans during WWII; the horrors suffered by Indigenous peoples who had much to fear from registering their children with the government; the long struggle for Black Americans to fully realize their voting rights promised by the 15th Amendment, but blocked by a century of deterrence from state laws, poll taxes, literacy tests, and violent intimidation.

“Territorial birthright citizenship is a major legal foundation on which our multicultural Canadian nation is built,” adds Cheong, “and it is urgently important that we defend against attempts to do away with it if we want to remain an inclusive, pluralist Canada in the future.”

Falling through the cracks

One would hope that countries with strong democratic foundations would have the strength to withstand challenges to the most basic principles of citizenship. But the 2014 Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act – which raised alarms about how easily political priorities could chip away at birthright protections – and current efforts by the US administration to undermine the 14th Amendment, threaten the very underpinnings of a just society.

One of the principle tactics employed by anti-democratic forces is control over documentation – birth certificates, social insurance numbers, voter cards, passports – that allow people to move freely about their country and participate in its democratic processes. According to UNICEF, more than 50 million children under the age of five – nearly a quarter of the global population – have not had their births recorded by their governments, which can severely limit their access to fundamentals like education, immunizations, health care, and voter registration.

“Birth certificates are a basic human right, because they are the documents that we need to obtain all of the other forms of official identification that make daily life possible,” says Cheong. “Most importantly, birth certificates are often the material building blocks that people need to secure citizenship. Statistical omissions – people who fall through the administrative cracks – are not necessarily accidents. Governments can strategically deprive unwanted minorities of rights and recognition by depriving them of the documents needed to establish that they exist as legal persons.”

Omissions from civil registers and other state systems are bureaucratic strategies that can be used below the formal letter of the law to prevent people from securing their citizenship, even if they are legally entitled to it. As hard as it might be for Canadians and Americans to believe such strategies could take hold in their countries, the truth is we are already on a slippery slope. In April, the US government declared more than 6,000 legal immigrants dead so they could cancel their social security numbers and force them to “self-deport,” robbing them of any chance to gain citizenship in the future, and de facto exiling their American-born children.

The United States hasn’t passed a comprehensive immigration bill since 1990, leaving states and cities to create a mishmash of policies in how they deal with documenting identities so they can award (or deny) public services based on increasingly draconian interpretations of eligibility. Although US citizenship is a national status and passports are issued by the federal State Department, birth certificates are issued by states, and each US state can further delegate that birth registration to counties or municipalities. As the American obsession with voter ID laws shows us, it’s a short road from questioning the absolute right of birthplace citizenship to determining that being a citizen at birth isn’t enough, and there should be other considerations to be seen as a real American.

“Citizens are dependent on those birth certificates,” says Bloemraad. “So Texas might decide to have different-coloured birth certificates for the people who can prove that at least one of their parents was a US citizen and the people who can’t. But California will refuse to do it. Vermont might refuse to do it. Massachusetts will refuse to do it.

“And then the State Department is going to have to do something. So if you wanted a passport, the federal government could say we’re only going to accept Texas birth certificates, not ones from California. And people in California who want their passport are going to scream because they’re US citizens. So it can get really messy, really fast.”

Despite anti-democratic forces deeply embedded in the current administration, the US court system is unlikely to allow a wide deviation from the norm when it comes to protecting birthright citizenship. In addition to decades of case law supporting the integrity of the 14th Amendment, alienating a large segment of its own population would create a massive underclass of native-born children without citizenship because their parents were undocumented or temporary immigrants. Undocumented status would become genetic, passed down to children and grandchildren, no matter how many generations before you were born on American land.

Canadians are often surprised to find out that birthright citizenship is not protected in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms; it exists only in legislation. Since the country’s inception in 1867, millions of people born on Canadian soil lost their right to live in Canada for a host of reasons, ranging from misogynist policies to simply not being in the country on their 21st birthday. Over the past 40 years, largely due to citizenship crusader Don Chapman and his Lost Canadians movement, the government has enacted a patchwork of fixes to correct the loopholes in the system. But without a constitutionally enshrined birthright promise, that system remains vulnerable to influence by those who want to narrow the definition of “Canadian” to suit their purpose.

Power to (some of) the people!

Perhaps surprisingly, a well-functioning democracy and a generous immigration policy don’t go hand in hand. The bulk of academic research suggests that allowing the general populace to have a say in issues of immigration and citizenship makes it more restrictive. The democratic impulse is not to be generous and hand out citizenship to all comers. Immigrants are welcome, but they aren’t us.

“There’s an analogy here to welfare chauvinism,” says Bloemraad. “Europeans, for instance, are very much in favour of a generous welfare state. They want to equalize the playing field. But they don’t want the ‘others’ to get it. So some people – some immigrants – don’t even get to be on the field. The same is true for citizenship and democracy. Those who won the citizenship lottery at birth automatically enjoy political rights through no effort of their own. They get to determine who else is allowed the full rights and promise of citizenship equality. But the non-citizens don’t get a say.”

This is the fundamental tension with birthright citizenship: it is both inclusive and exclusive. If you were born in the club, you are in the club – but some of the snootier members keep asking to check your ID. Citizenship, then, is not just a legal status but a cultural battleground – a symbol of who counts, and who decides who counts. As nations face growing migration and identity anxieties, how we define citizenship will determine whether democracy remains a shared ideal or retreats behind locked gates.