The Boy Who Carried Books

James Magok Achuli experienced the horrors of civil war and living in a refugee camp before education changed his life forever.

*We have respectfully borrowed the title of James Magok Achuli’s book in progress, The Boy Who Carried Books.

Part 1: Life amidst war in south sudan

When asked about his early life, undergraduate student James Magok Achuli has a response that most of his peers have thankfully never endured.

“My childhood was stolen away from me. The future has always been very unpredictable,” explains Achuli, who was born and raised in South Sudan. Ethnic violence and a civil war marred the newly formed country between 2013 and 2020, meaning Achuli spent his formative years as an internally displaced person — the term for citizens who have not crossed a border to safety and are instead on the run in their home country.

When Achuli was a child, a typical day was spent without food in a refugee camp alongside his family, friends, and thousands of other citizens fleeing the war and violence. “We were lucky if we had a meal a day, and there were some days I didn’t eat at all.”

While education also wasn’t a reality in the camp, that didn’t deter the young Achuli, who cherished a small collection of books he kept protected in his waterproof UNICEF backpack. “There was this helicopter that would bring us food in the village,” he recounts. “I was always curious how it flew, and my father told me, ‘If you learn how to use the book and the pen, you will fly that metal in the air.’ It was always in my mind to go to school, and my books were like my education. They were a symbol of hope for me and the future.”

“It was always in my mind to go to school, and my books were like my education. They were a symbol of hope for me and the future.”

But before he could realize his dream of a formal education, Achuli was displaced by war and separated from his family. At the age of 12, he won a scholarship to a school that neighboured military barracks; when a second civil war broke out, the school he attended was eventually targeted and children were forcibly conscripted into the army.

“One night I was studying with my friend Deng — he was studying chemistry and I was reviewing geography. Suddenly there was a loud explosion and shooting, and kids ran and jumped through windows. Deng was shot in the stomach and was bleeding to death. In the middle of the night, I told him I was going to run away, and he said the soldiers would kill me. So, I took Deng’s blood and spread it on me, and we pretended to be dead people. We hid under a huge table all night long, and in the morning Deng died. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever experienced.”

Achuli was eventually found alive by the government forces and conscripted into the army, where he was trained to become a child soldier. He quickly became an asset to the unit’s commander, who used Achuli’s expertise in math and geography to help him with terrain. After three months of working alongside the commander, Achuli escaped with his waterproof backpack and books. He jumped into the river, swam across, and then walked four hours to a neighbouring town, where he was able to take shelter with others in a church. The group was planning to walk to a refugee camp in Uganda, more than 500 kilometres away.

“One of the toughest questions I had to ask myself was whether to go with this group. I didn’t know where we were going, to be honest. But from what people told me, we were going to find food, safety, and education, so when I heard those words, I was really hopeful and excited. I joined them without any close family or relatives to help me.”

The route to Uganda was difficult and treacherous for the group of over 100 refugees: “I had to rely on mud, leaves, snails… anything to fill my stomach since there was no food. I had to beg from people who had food for their own children,” explains Achuli. Group members, including a close adult friend who watched over young Achuli during the trek, were killed by snakes, hyenas, and crocodiles.

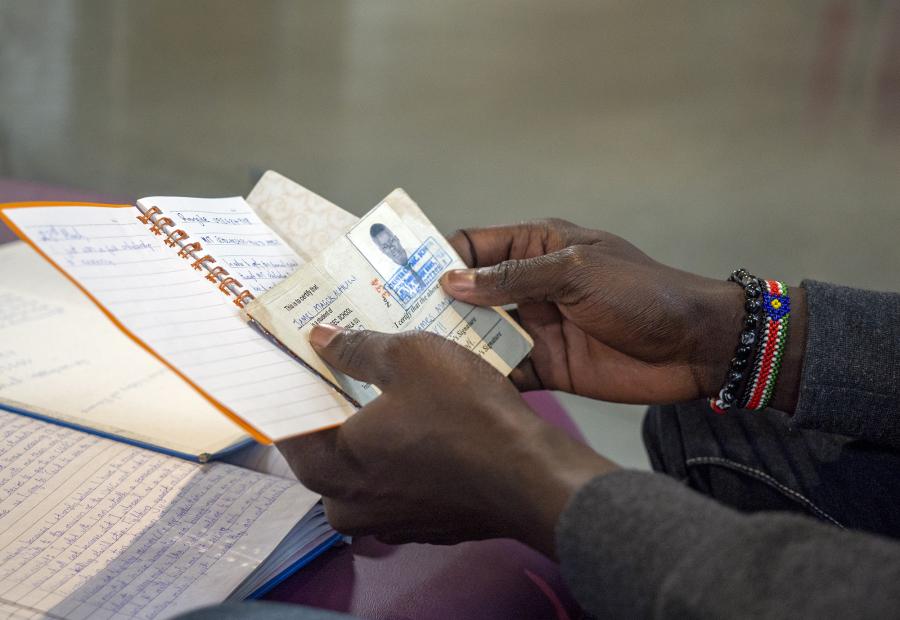

But perhaps the most harrowing experience for Achuli took place along the riverbank during his trek to the refugee camp. Groups were being ambushed along the route and killed based on their names and what tribe it was thought these people belonged to. Achuli was mistaken as a member of South Sudan’s largest tribe, and soon he was tied up and a black cloth was placed over his head. He pleaded he was from the Mundari tribe, the smallest tribe in the country, and told his attackers to look at his books for proof.

“A woman there actually listened to me and looked at my books, which described where I was born, my mother, and my village. Those little stories I wrote and those books saved my life because if I didn’t have those books, they would have killed me like they killed other people.”

When Achuli arrived in Uganda, he was taken in as part of UNICEF’s orphan and vulnerable children program. While there was food and education in this camp, Achuli’s mind was constantly full of memories and worries.

“The violence disappeared, but not in our brains. We always had those memories in the camp. Although it was safer and we had access to UNICEF-funded schools, I was honestly worried about my future. People are born and raised in these refugee camps and die there, especially in Africa. Refugees don’t have access to higher learning. I was really, really worried; I was constantly thinking about my education because I knew that was my hope.”

Part 2: the transformative power of education

“I’m one of those people who looks for opportunities in the darkest moments,” reflects Achuli. “I think in the middle of adversity you have to surround yourself with positivity. It could be surrounding yourself with the right people, and if you’re like me — someone who went through the horrors of war — then you have to be hopeful. But also like me, you have to endlessly fight for your goals, because it’s really important.”

Growing up, one of Achuli’s most steadfast goals was to get an education. From the time his father told him that if he “learned how to use the book and the pen, he would one day fly a helicopter in the air,” Achuli understood the power of education to change lives. During the three years he lived in a Ugandan refugee camp, Achuli was known as the boy who carried books, and was an advocate for those around him; he educated his peers in the camp about gender-based violence, HIV, and AIDS, and the importance of peace and education. Knowing seven languages, he also acted as an English and Arabic interpreter.

“Back home, women would be sexually assaulted and beaten — beating women is on a different level there — and because people aren’t educated they don’t have the courage to speak up,” explains Achuli. “I couldn’t just watch someone harass a girl in a refugee camp and keep quiet about it. That’s one thing that education has helped me with; speaking up and thinking more critically about things. As Nelson Mandela once said, ‘Education is the most powerful weapon you can use to change the world.’”

“If you’re like me — someone who went through the horrors of war — then you have to be hopeful. But also like me, you have to endlessly fight for your goals, because it’s really important.”

To achieve his dream of a formal education, every day Achuli ran kilometres from the refugee camp to an internet café, where he searched for scholarships online. Then one day, he came across an article from the UN Refugee Agency about South Sudanese high school students who received scholarships to study around the world through United World Colleges (UWC). Achuli was mesmerized by the opportunity and spent a week learning about these colleges that had a shared mission of making education a force to unite people for a peaceful and sustainable future. When he applied and was invited for an interview in Uganda’s capital of Kampala, Achuli’s reaction “was crazy.”

“I was punching the air and screaming; I was really excited. I went for the interview and two days later I got a call from the head of the national committee, and he said, ‘Congratulations James, you’re going to Armenia on a full-ride scholarship for their baccalaureate program.’

“I couldn’t stop crying. I cried and cried and cried. It was a huge relief. From the articles I read, I knew my life was going to change forever. But I was also crying because I was going to leave a lot of people behind. The pain will not go away because I always think of them.”

In addition to leaving behind the friends he made in the refugee camp, Achuli was further separated from his parents, who did not have access to letters or emails in South Sudan. The last time Achuli physically saw his mother was in 2014; his father was sadly killed in 2015 by unknown armed men. To this day, he struggles with the hurdles of speaking with his mother from abroad; “I’ve been able to Zoom with my mother once in over five years. It’s been very hard.”

But Achuli gained a sense of family when he arrived at UWC Dilijan, his new school in Armenia, and more than 200 students and staff lined up from the entrance gate to the kitchen to greet him. “They were clapping and said, ‘Welcome James!’ and I said, ‘How do you know my name?!?’ I felt like this was home; everyone was so happy to welcome me and were giving me hugs, which are new to me but were good. The cooks were waiting with cakes and muffins — something I never had in South Sudan or Uganda.”

Achuli flourished at school, and when it was time to explore post-secondary options, UBC was his first choice. His school nominated him for UBC’s Karen McKellin International Leader of Tomorrow Award, a full scholarship covering all program and living costs for undergraduates demonstrating superior academic achievement, leadership skills, involvement in student affairs, and community service. Achuli competed against more than 1,500 students from across the globe before receiving the award and an acceptance letter to UBC Okanagan.

“It’s incredible. I love Canada, and UBC is one of the top universities in the world. I knew from my geography studies that BC is an incredibly beautiful province,” he says. “Coming to the Okanagan, it’s a smaller campus than Vancouver and it’s still growing, so maybe we will grow together. It’s such a close-knit community where you get to know people quicker.”

Since joining UBCO, Achuli has immersed himself in the university experience. In addition to joining the Afro-Caribbean Club and the Students’ Union, he is also a member of the Heat Cross Country Team, under the guidance of Olympian Malindi Elmore. “I’m a long-distance runner. From my life in the refugee camp, I was always running to search for scholarships online. I’m so thankful to my Heat teammates and coaches, who have been so kind and supportive.”

Currently a student in the International Relations program, Achuli hopes to one day work with children to help them realize their goals and needs. “No one should go through what I went through,” he says. “I can’t predict the future but through my education I want to help people displaced by war, whether they are refugees, immigrants, or asylum seekers. These people aren’t criminals or villains, and they’re much more than victims. They are human beings just trying to survive.

“Helping them survive is very important to me.”