Opera on the brain

How does operatic training affect memory, cognitive functioning, and learning?

In her 28 years at UBC, Nancy Hermiston has seen — and heard — her fair share of opera virtuosos. But several years ago, the Voice and Opera Divisions director worked with one master’s student she will never forget. “She had the most beautiful voice, and was such an intuitive actress,” says Hermiston. “You couldn’t take your eyes off her.”

There was just one issue: when she started her opera training, this student had a severe learning difficulty, or “learning difference,” as Hermiston refers to it. It would take her months to learn and perform an opera excerpt correctly. But as training progressed, Hermiston observed dramatic improvement, until the student was able to reduce that learning period to just a few weeks. “It was incredible to watch,” says Hermiston.

By the time she finished at UBC, the student received an offer to perform a major role in an opera in Ireland. She only had two weeks to learn the piece, remembers Hermiston. “But she did it. And the conductor said she knew her role better than anybody.”

As memorable as this student was, she was by no means the only UBC opera student to overcome learning differences that Hermiston has encountered. She’s taught dozens of students with conditions such as dyslexia or attention deficit disorder whose learning speed, knowledge retention, and concentration significantly improved during training. Her hunch was that the combination of the complex set of skills that opera students have to learn — including singing, acting, and language acquisition — was influencing the brain to cause these improvements.

If Hermiston was right, she thought, perhaps this could be applied to a therapy for people with learning issues. Or maybe it could just be one more piece of evidence showing the importance of music in all of our lives. “But I wanted to have some actual proof that these changes in the brain were indeed happening,” she says.

That proof could come this spring, when early findings from the Wall Opera Project are expected to be revealed. Funded by the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies, this large multidisciplinary research collaboration has been looking deep inside the brains of UBC opera students to figure out what, exactly, is happening in there.

The Power of Music

Hermiston didn’t think that it would take over a dozen years to get a research project like this going, but such is the case with getting funding for research at the intersection of art and health, she says. In 2015, though, and completely by chance, she met UBC Physical Therapy professor Lara Boyd, who directs the university’s Brain Behaviour Laboratory.

“I’ve always been interested in music, but I’m not a musician,” says Boyd. “And even though we all know that music has this fundamental impact on us, we don’t dedicate funding to understanding that impact. So, it was a really happy coincidence to meet Nancy, and then we were just incredibly grateful to the Wall group for funding this.”

"humans have had music and art in our lives for so long. why? i'm strongly suspicious that it's given us some type of evolutionary advantage."

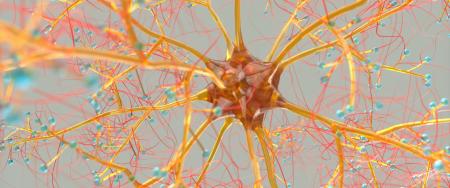

Boyd’s academic interests are all about how behaviour and the environment change the brain. A big part of that looks at something called “neuroplasticity”, which generally just means that whatever we’re doing or experiencing alters the brain. It turns out that behaviour is the largest driver of how our brains change, says Boyd. “I always think of neuroplasticity as this amazingly optimistic concept because it really gives you this idea that you can shape the brain to be how you want it to be based on your behaviour.”

In recent years, mounting evidence has suggested that music can have significant impacts on neuroplasticity. One study from 2013, for instance, showed that musical training led to improvements in reading ability, verbal memory, and second language pronunciation. Even listening to music has been shown to induce beneficial brain plasticity.

The Wall Opera Project is focused on one fundamental neuroplasticity question: How does opera training impact memory, cognitive functioning, and learning? To find out, Hermiston and Boyd teamed up with psychology professor Janet Werker as well as School of Music postdoctoral fellows Anja-Xiaoxing Cui and Negin Motamed Yeganeh. By comparing the MRI brain scans of opera student participants before they start their training and a year later, the researchers are hoping to zero in on the specific changes happening in the brain. To further tease out these potential changes, the researchers are also comparing the opera participants’ MRIs to control groups of musicians, second language learners, athletes, and drama students.

The Complexity of Opera

Although the research team is in the midst of crunching the data right now, Boyd is confident they will see changes across all groups, but particularly the opera students. Part of her confidence comes from the breadth of other studies on brains and music, including those showing the protective effects of music. For example, she points to research suggesting people with higher musical sophistication have lower rates of dementia and that people with musical training have better outcomes after stroke.

But Boyd also thinks that the significant changes they could see in the opera students will indeed be rooted in Hermiston’s hunch — that the complex combination of skills that opera students are engaged with is conferring a cognitive benefit. “Singers sing and actors act and athletes are very physical, but what’s special about opera performers is that they do all these things — and in a second language,” says Boyd. “It’s actually bonkers that anybody can do this.”

If that turns out to be true, it could encourage further research into whether multi-tasking should be incorporated into certain therapies. For instance, Boyd says that we know exercise can be hugely beneficial for brain plasticity, so maybe therapies for young kids struggling in school could include exercise and singing at the same time.

"singers sing and actors act and athletes are very physical, but what's special about opera performers is that they do all these things – and in a second language. it's actually bonkers that anybody can do this."

The project could also be a small step in helping us understand the core function of art in our lives, says Boyd. “Humans have had music and art in our lives for so long. Why? I’m strongly suspicious that it’s given us some type of evolutionary advantage. There’s something about it that makes us healthier, stronger, more resilient, smarter — more neuroplastic is my bet. And if we discover even a little bit around that, I would be beyond thrilled.”

Nancy Hermiston would be thrilled, too, and bets that confidence is also playing a role here. She thinks again about that young opera student who overcame her learning issues and performed in Ireland. “The way that she learned to communicate with the audience and portray roles was tremendous. For young people, seeing that impact they can have is so huge. I see it all the time — it gives them such a boost of pride. It tells them, ‘Yes, I can do something special.’ And they are special.”