The stories that change us

A warm and vibrant centre in Vancouver’s Chinatown is leading the way for a more inclusive — and transformative — kind of storytelling.

Life is steeped in story. We make sense of our histories and the world around us via story. In myriad ways, we are all moved — and even changed — by stories.

Sometimes, these transformations happen in the quiet of our room, between the pages of a powerful book. Other times, they happen in the company of others, when a friend or family member, or even a stranger, shares a story that transforms how we view ourselves or those around us.

And still other times, if we are lucky, we encounter a place whose entire mission is to share important, but little-known stories about people who have faced incredible odds and found ways to overcome them — stories that have the power to help us see or feel seen, to broaden national narratives, and to instill a sense of collective pride and belonging.

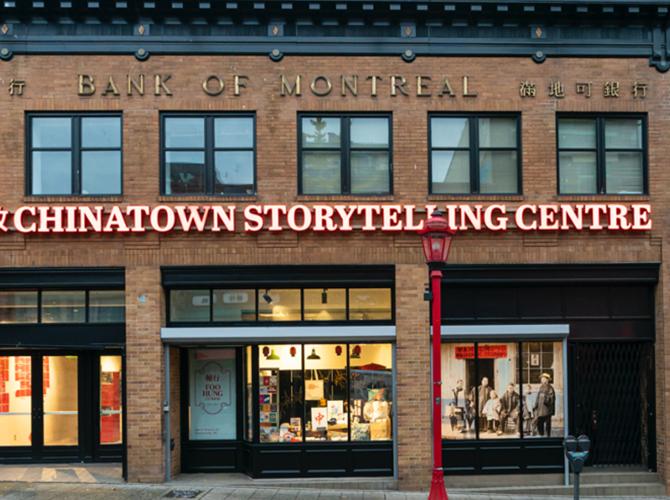

The Chinatown Storytelling Centre is one such place.

Recognizing the forgotten

Opened in November 2021, the Storytelling Centre engages visitors on the history of Vancouver’s Chinatown and the stories of its early Chinese community, who contributed not only to the city’s development, but to the making of Canada itself. It’s a history that has often been left out in prevailing narratives about Canada’s past — but the passionate team behind the creation of this stunning space in Vancouver's Chinatown, many of whom are UBC alumni, are on a mission to change this.

At the forefront of the Storytelling Centre’s efforts to build a broader and more inclusive understanding of Canada’s history is UBC alum Carol A. Lee (BA’81, LLD’19). A business and community leader, who also serves as the Chair of the Vancouver Chinatown Foundation, Lee has long been moved by the history of the Chinese community in Canada and motivated to share their stories more broadly.

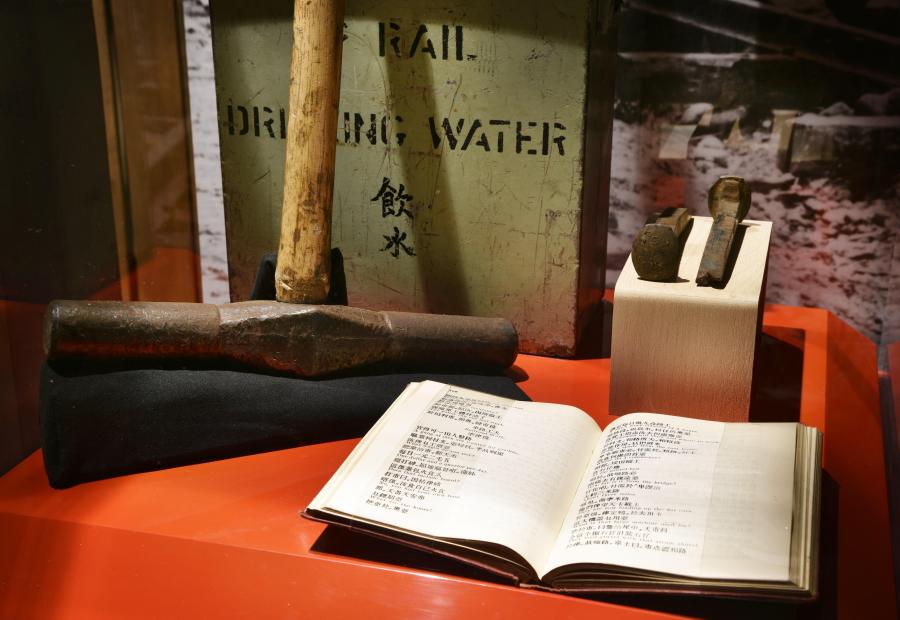

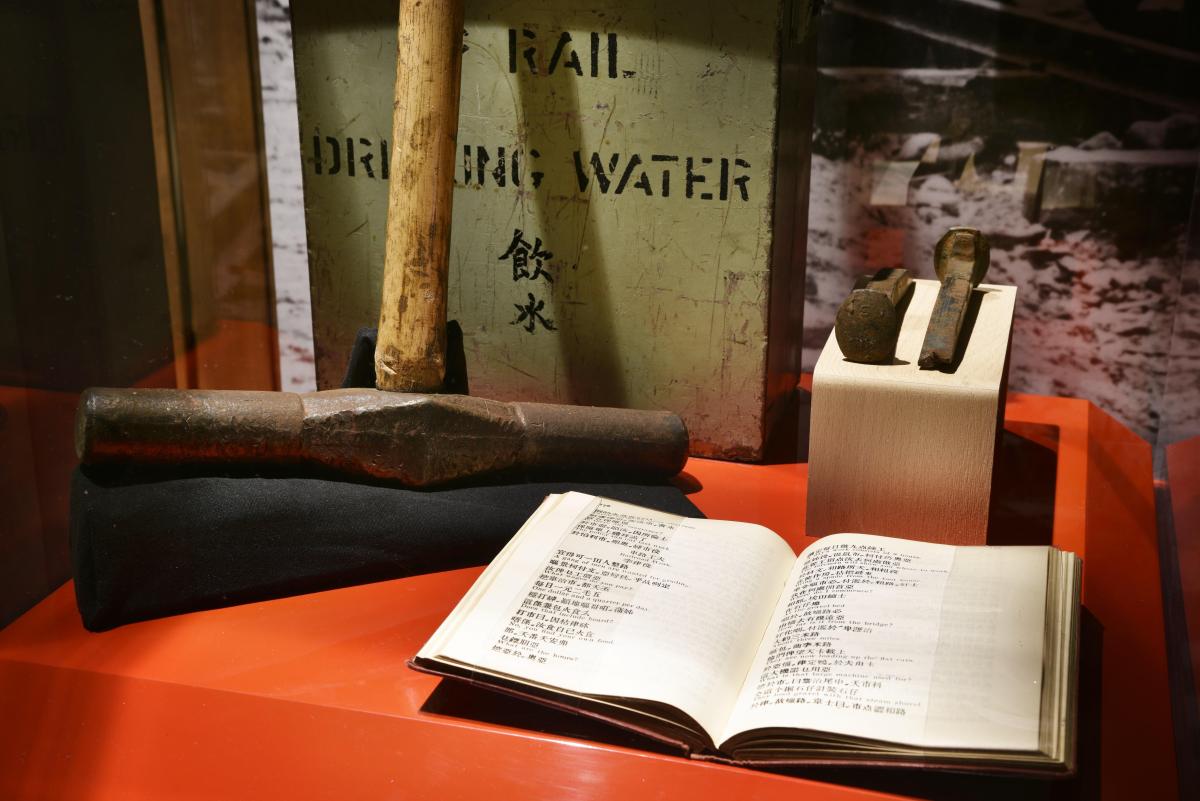

Speaking with her during a recent visit to the Storytelling Centre, I can hear the deep respect she has for the early Chinese migrants, who not only built Chinatown, but whose “blood, sweat, and tears,” she tells me, were indispensable to completing the Canadian Pacific Railway and thus uniting Canada from coast to coast.

Chinese labourers, Lee says, were given the “most difficult, backbreaking, and dangerous work.” In fact, one sobering estimate suggests that a Chinese worker perished for every mile of track laid. Yet, despite the perilous work, the Chinese were paid less than half of what their white counterparts received, and when the CPR was completed in 1885, they were stranded in a country that no longer wanted them, unable to return home when contractors reneged on their promise to pay for their passage back to China.

Recognizing the contributions of these workers is one reason why Lee, a third-generation Chinese Canadian whose family has been in Canada for over a century, sought to create a space like the Chinatown Storytelling Centre. These workers died and never really got any recognition, she explains, and “it wasn’t even till I was much older that I even understood the story.”

Capturing experiences from all walks of life

While the Storytelling Centre covers important overarching chapters in the history of the Chinese Canadian journey over the past 150 years, it does so through the lens of Chinatown and by zooming in on the personal stories that bring these chapters to life. These stories reveal how Chinese Canadians persevered despite the racism and discrimination they faced on a regular basis — from the requirement to pay a head tax simply to gain entry into Canada to the countless ways in which their second-class status was reinforced in everyday life, such as being banned from using public pools, relegated to the back of movie theatres, and barred from working in numerous white-collar professions.

Recent UBC graduate Ryan Iu (BA'19, MA’22), Research and Program Assistant at the Storytelling Centre, tells me that its aim is to “resurface individual stories about [the Chinese Canadian] experience — their past, their struggles, their celebrations.” The team has collected 180 of these stories already, Iu says, which cover individuals from all walks of life. Some of these stories are woven throughout the main exhibits, but what’s remarkable is that the entire collection is available for perusing in two interactive story kiosks located in the main exhibit space. The stories are accompanied by photos or videos — providing names, faces, and voices to the many individuals whose contributions might have remained unknown but for the work of Lee’s team.

Scrolling through the kiosk, visitors get a sense that every voice matters in telling the story of Vancouver’s Chinese Canadian community. Individuals as varied as teachers, tailors, and laundry workers appear alongside lawyers, poets, and politicians who each made a difference in and for their community. Lee tells me that there wasn’t any one “Napoleonic figure” in the story of Vancouver’s Chinatown. Instead, there are many individual stories that collectively have a big impact.

Revealing Chinatown’s early boundary breakers

The stories the Chinatown Storytelling Centre is particularly intent on uncovering and sharing are the untold and lesser-known ones among Chinatown’s elders — “knowledge that nobody has ever documented and recorded,” explains UBC alum April Liu (PhD’12), Manager of Public Programs & Education. There’s an urgency to this work because “we’re losing elders,” says Liu. “We need to get the stories that are in danger of disappearing imminently.”

One such story that the team has been able to uncover, and which is on display in their special lobby exhibit Raised in Chinatown, is that of Donna Chan, founder and captain of the Vancouver Chinese Girls Drill Team. In 1958, the teenage Chan pitched the idea of starting a drill team among her female friends. The girls were game and the team proudly embraced their Chinese roots by designing a uniform modeled on the warrior outfits of traditional Cantonese opera — complete with stunning headdresses.

Liu stresses how gutsy a move this was: “these girls dressed themselves up as warriors for drill team.” And they continued to show their gutsiness when, after winning the trophy for Best Performance in PNE’s 1959 parade, they were regularly in the public eye — participating in numerous civic parades and essentially taking centre stage during a time when women were expected to stay at home. Liu notes just how boundary breaking they were — “to come out and be athletic and design their own fashion and how they wanted to be seen” — and how excited the entire team was to have the chance to share this story.

It’s one that reveals just how important the Storytelling Centre’s efforts are in broadening our understanding of the history of Vancouver’s Chinatown and those who made an impact on the community, but whose histories are not published “in the official realm,” says Liu. “They’re not doctors, engineers, pharmacists, or teachers. It was a youth activity, and very ephemeral — but so important, so visible, and,” she says again, “so boundary breaking.”

“What we did rather than…what people did to us.”

Uplifting stories like that of the Vancouver Chinese Girls Drill Team are not stories that Elwin Xie, a fourth-generation Chinese Canadian, grew up hearing. That’s why, when he walked through the Chinatown Storytelling Centre for the first time, his initial thought was: “Finally, there’s a place to have stories of my community.”

Since then, Xie has been particularly moved by the Raised in Chinatown exhibit, which focuses on how Chinese youth in the first half of the twentieth century lived and thrived amidst the exclusions they faced. As he shared in this interview with CityNews shortly after the exhibit opened, it’s “so, so important to be able to tell our story, how we lived, what we did rather than constantly hearing about what people did to us.”

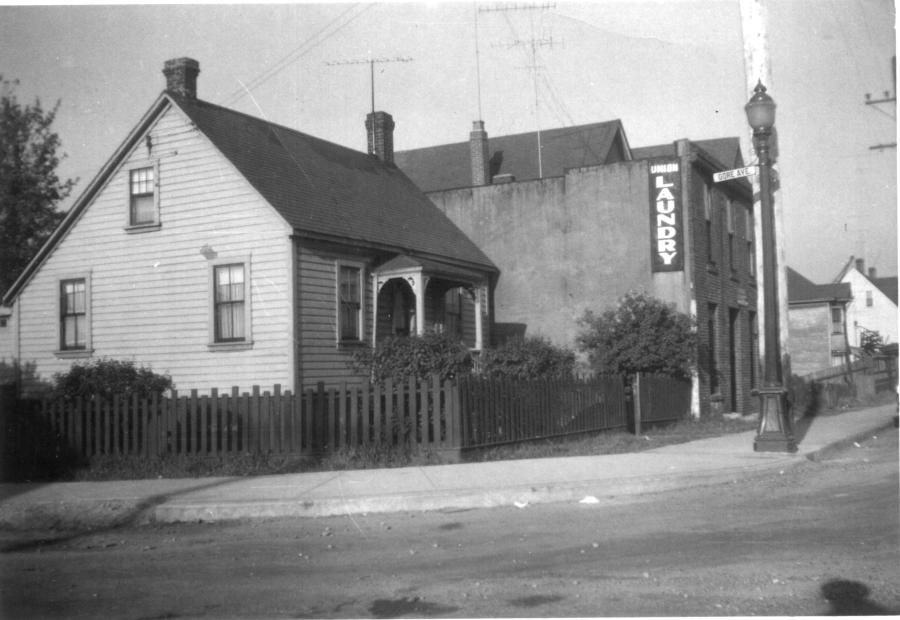

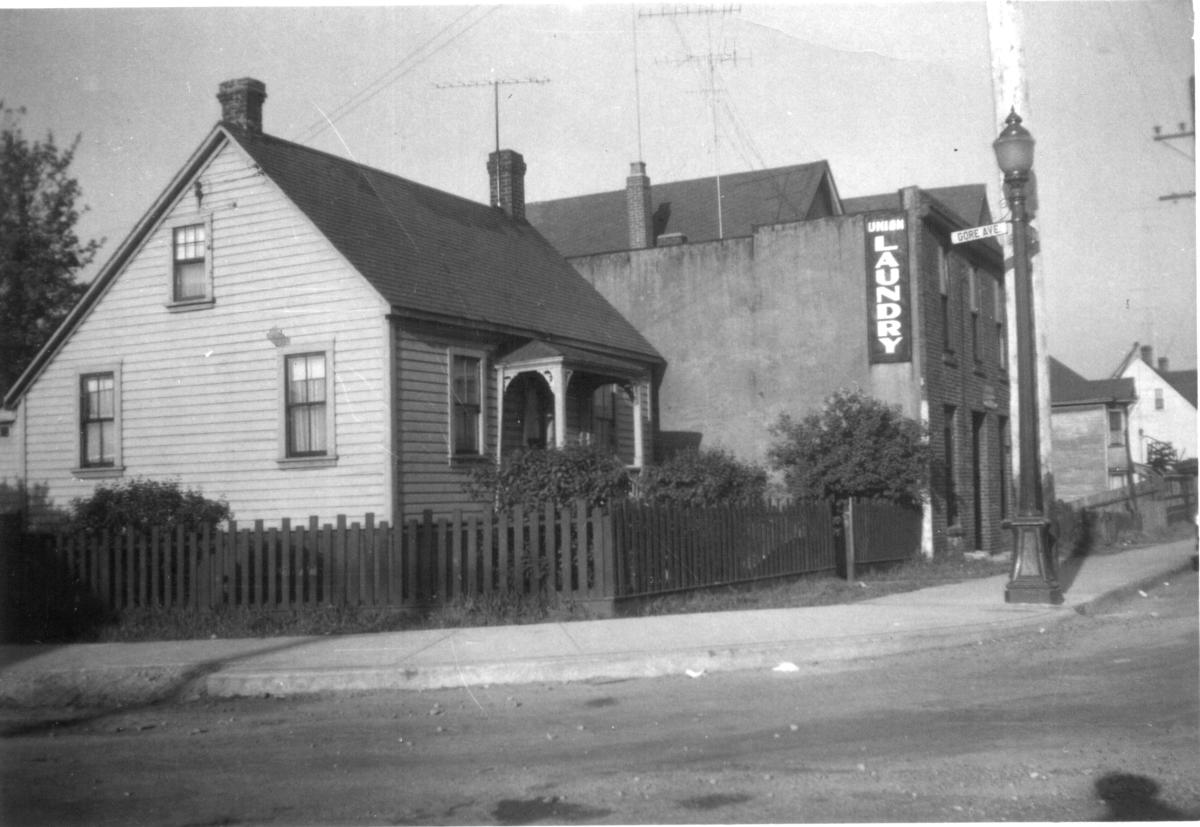

Having grown up in Vancouver in the 1960s and 70s, Xie tells me that he wishes there was a place like the Chinatown Storytelling Centre when he was a youth, because its stories would have provided an uplifting counterpoint to the narratives of his time, which were often “sad, depressing, embarrassing stories” that perpetually cast Chinese Canadians in stereotypical ways. “We're having to wash other people's dirty laundry, we're panning for gold, we're unskilled, we don’t know how to do anything,” Xie recounts. “As a kid, that's all you hear — the negative stories.”

That’s why he feels a sense of pride when he walks through the Storytelling Centre and reads stories that show how “the Chinese were not just beaten down….They fought back and they stood up for their rights.”

What is also significant for Xie is the permanence of the space. According to Lee, the Storytelling Centre “is the first permanent exhibition space that shares the story of the Chinese Canadian experience over the last 150 years.” While temporary exhibits have popped up in different cultural institutions that cover Chinese Canadian history, their eventual dismantling has made Xie wonder if his community’s story will perpetually remain “just a footnote” in mainstream narratives. With the creation of this warm, vibrant, and welcoming space, he doesn’t have to wonder about this anymore.

“What I love about the Chinatown Storytelling Centre,” he says, “is that there are stories about us, done by us, made for us.”

Xie also appreciates the diverse voices and experiences that are captured in the story kiosk collection. “I like how the [Storytelling Centre] has coverage of working-class occupations,” he shares, “such as tailors, cooks, farmers, laundrymen, tofu makers, butchers…families and individuals who did a lot of the heavy lifting in society but received no recognition in the past.”

Xie tells me that his own parents had a laundry business on the edge of Chinatown, and his family’s story is actually one that is featured in the Storytelling Centre’s collection. “For me, for the first time, I am able to tell my family story of growing up in a Chinese laundry in the poorest part of Vancouver. This is huge,” Xie explains, because “there has been a real reluctance within the community and museums in general to shine a light on this occupation.”

Breaking boundaries in interpretive storytelling

In its pursuit of truly diverse stories, which ensure that experiences like Xie’s are included, the Chinatown Storytelling Centre is itself a boundary breaker in the interpretive arena. Its very name, for instance, intentionally moves away from the more typical “museum” designation. From Lee’s perspective, “museum” signifies a place that is “more formal, that might even be slightly intimidating. Does it presuppose,” she asks, “that you should have some knowledge before you come into the place?”

So instead Lee and her team chose “storytelling centre” because they wanted to create “something that was very accessible, something that seemed very friendly, even for children.”

Another inclusive aspect of the Chinatown Storytelling Centre’s interpretive approach — one which stood out for Xie right away — is the space it holds for the stories of mixed-race individuals. Xie shares that when he was growing up, such individuals were considered “social pariahs.” Canada’s restrictive policies, especially after the passing of the Chinese Immigration Act in 1923 (also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act), which virtually stopped all immigration from China until 1947, meant that mixed-race families were not uncommon in Vancouver’s Chinatown. However, little has been shared about these families and their descendants, and Xie notes just how significant it is to read stories about such individuals at the Chinatown Storytelling Centre.

Liu herself is particularly energized by the Chinese and Indigenous connections that she and her colleagues have been unearthing in their research. She notes how the Chinese and Indigenous peoples intermarried, farmed together, and traded with each other, and the similar kinds of exclusions they faced — which, quite literally, extended beyond the grave.

“Back in the day, there was even exclusion in the cemeteries,” says Liu, “so you couldn’t even be buried in the same cemetery as the dominant white people.”

One little-known story that Liu is particularly moved by is that of Wah Kwan Gwan, a legendary prop master in Chinatown who was of Chinese and Indigenous descent. Gwan lost touch with the Indigenous side of his family after he moved to China with his father. There, he was raised and trained in the art of prop-making, performance, and costuming for Cantonese opera.

When Gwan returned to Vancouver as an adult, he was embraced by the Chinese opera community in Chinatown and went on to teach for the next four decades. Although he made a significant impact among the opera community, “nobody else really knew his name,” Liu says. He never received “any mainstream attention from the art scene in Vancouver.” Fortunately, visitors can now learn about Gwan in the story kiosk at the Storytelling Centre.

“I think his life is incredible because it just captures how intersectional we are here in Chinatown,” reflects Liu. “I would love to see more of these stories come forth, to show how we're interconnected. And how really diverse Chinatown has always been.”

The Storytelling Centre, like Chinatown, is for everyone

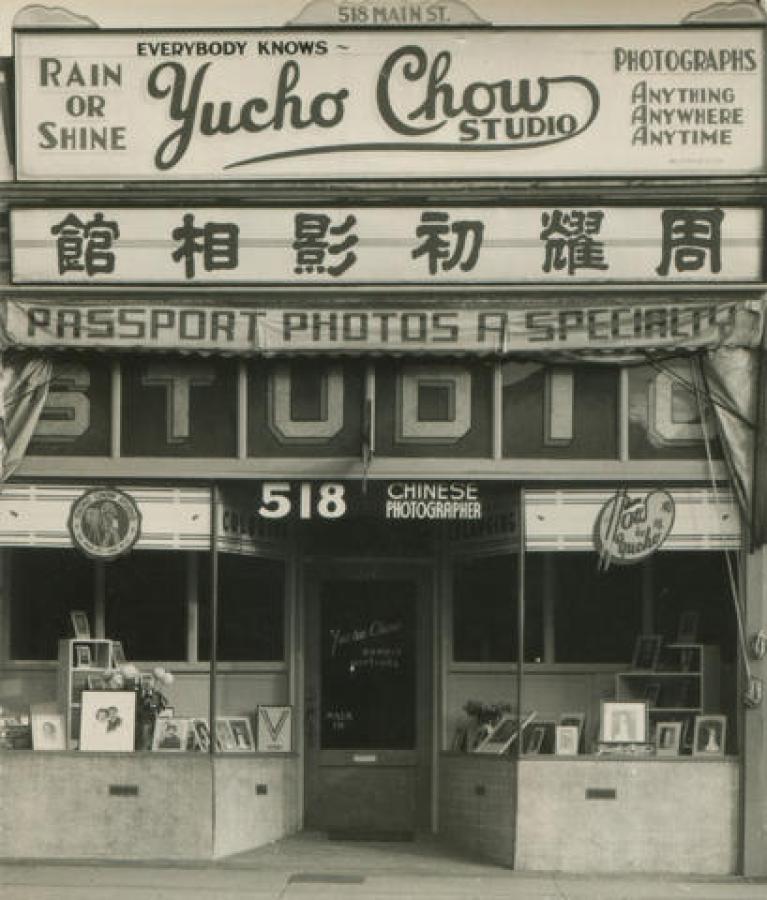

Chinatown’s enduring diversity and appeal certainly come through in the Storytelling Centre’s stories and exhibits. One room in the main exhibit space is even devoted to telling the story of early twentieth-century photographer Yucho Chow who, Iu tells me, took portraits not only of the Chinese, but also of other minority groups, like the South Asian and Black communities. The Storytelling Centre’s beautiful re-creation of Chow’s studio features a selection of his portraits and reveals the diverse clientele whom he regularly welcomed into his studio.

Just as Chinatown has always appealed to people of diverse backgrounds, so too has the Chinatown Storytelling Centre since its opening in 2021. According to UBC alum Lisa Seed (BA’83), who is the Chief Operating Officer of the Vancouver Chinatown Foundation and oversees operations for the Storytelling Centre, “visitors come from all over the world and they always find something that resonates with them,” a story or artifact that draws them back to their own history. “We see this in the [comment] tags that people leave,” she explains, which reveal “that it's been a moving and meaningful experience.”

Liu herself has observed how being in the space will spark memories for visitors of their own family histories and migration stories, noting that their response shows “a need for these kinds of spaces,” ones which enable people to feel seen and remind them that their histories matter and are worth celebrating.

Ultimately, Lee hopes that the Storytelling Centre will become a “community hub,” a place where people of all backgrounds can gather for engaging events and programs, and where they will not only be able to learn about the Chinese Canadian story through the lens of Chinatown, but also see their own story in the universal themes evident throughout the exhibit space: that of struggle, perseverance, resilience, and ultimately triumph in the face of challenging odds.

Towards a revitalized Chinatown

Lee’s hopes for a lively community-oriented centre extend to Chinatown as a whole, a neighbourhood she is passionate about protecting and enhancing. In fact, the Chinatown Storytelling Centre is just one project among many in her work with the Vancouver Chinatown Foundation, a charity she helped found in 2011 whose mission, she says, “is to revitalize the neighbourhood while preserving its irreplaceable cultural heritage.” The Foundation is engaged in numerous initiatives — such as their social housing project at 58 West Hastings that will provide 231 homes and a 50,000 sq. ft. health centre — all of which will help ensure Chinatown’s economic, social, and cultural vitality in the long run.

When I ask Lee what drives her efforts to revitalize Chinatown, she returns to the people and their stories and experiences, which make this neighbourhood so meaningful to her:

“This particular Chinatown is the place where after the railroad, Chinese workers congregated and lived because they really weren't allowed anywhere else. And so to me, this is a place that represents that sacrifice, the contribution of those earlier generations.”

Many of us have come across stories that have moved us, and that may have even fundamentally changed how we see the world and our place in it. For Lee, encountering such perspective-enlarging stories has propelled her to do what few, I think, would have the energy, vision, and tenacity to take on: ensuring that such stories have a home of their own, a space where they are preserved and poignantly presented, and where they hold transformative power for those lucky enough to experience them at the Chinatown Storytelling Centre.

FOR MORE ABOUT THE CHINATOWN STORYTELLING CENTRE

- Check out Our Journey Continues

On June 29, the Storytelling Centre’s new exhibit Our Journey Continues opens, which looks at how the Chinese Canadian community overcame past injustices stemming from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923. Plan your visit. - Share your story

Do you have an untold personal or family story connected to Vancouver’s Chinatown that you would like to share? Submit your story. - Volunteer at the Storytelling Centre

There are a variety of volunteer roles available. Check out the roles and join a team dedicated to revitalizing Chinatown.