Opinion

The complex legacy of sports journalist Lou Marsh and his trophy

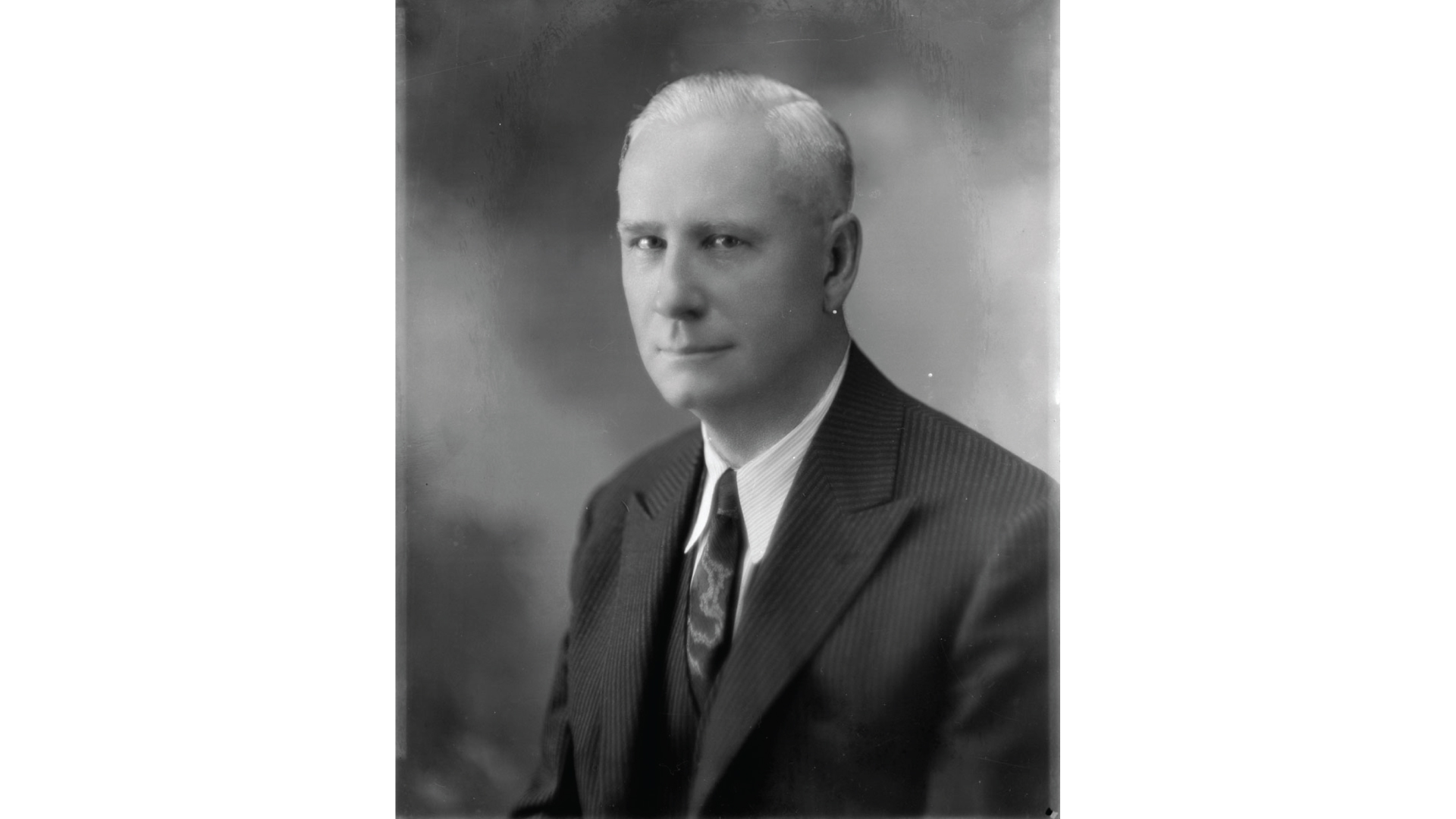

In September 2022, the Toronto Star announced it would retire the name of its famed sport reporter and editor, Lou Marsh, from its trophy honouring Canada’s top athlete. When Marsh passed away suddenly in 1936, the Star brought leading Canadian sports journalists together to commemorate his contributions to their industry by establishing the coveted Lou Marsh Trophy.

Growing public concern over the racism voiced in Marsh’s writing has made this name-change timely.

When people first name a building or a trophy or create a monument to honour someone, they don’t start off by imagining a day that the named person will fall out of favour. They envision creating an everlasting tribute to someone who they believe achieved something so impressive that it deserves public recognition.

As fitting as each tribute might seem at its beginning, they are all open to contesting, especially as our understanding of the past changes.

Today’s heroes may well become the next generation’s villains or be completely forgotten. If we are fortunate, however, that new light will reveal crucial insights into ourselves as individuals and as a society, and hopefully help to create a better future.

Harmful sports reporting

The Toronto Star’s decision follows those by other organizations, including sports teams, that have taken stock of a broader yearning for understanding and justice. While we do not dispute the wisdom of the Star’s action, we are compelled to shine a light on the important legacies that Marsh left to Canadian sport. We wonder: what important lessons we can learn from Marsh’s work as a sports journalist?

This question has led a team of scholars, myself included, to scrutinize the body of Marsh’s sports reporting in the Star. Lately we have been focusing specifically on what Marsh said about Tom Longboat, the great Onondaga runner from Six Nations of the Grand River who first gained fame as an athlete in the early 1900s.

Like Marsh, Longboat’s name is found on a major Canadian sports trophy, one handed out annually to top Indigenous athletes in Canada. The paths of these two men’s lives crossed often and over a long period, with Marsh at times playing bit parts as the athlete’s manager and trainer, but more often as the chronicler of his exploits through newspaper articles.

What Marsh said about Longboat in his capacity as a Star reporter demonstrated his brilliant storytelling style and mastery of the written word. But it was also racist — and sickeningly so.

In his many writings about Longboat, Marsh reproduced some of the most damaging and dehumanizing tropes about Indigenous people. His word choices went well beyond public name calling, which is a surface way of thinking about racism, to evoke ideas that shaped and reinforced Canadian attitudes towards Indigenous people.

He depicted the runner as being foolish, stupid, and shiftless, as a man incapable of managing his own affairs, as someone happy to be controlled by white men in power, and as being unwilling to commit to settled life. He questioned and undermined Longboat’s approach to running and his training methods, regularly calling him lazy and undisciplined.

Runner Bruce Kidd, himself a recipient of the Lou Marsh Trophy, critiqued Marsh’s questioning back in 1983 in his compelling paper, “In Defence of Tom Longboat.”

Marsh also demeaned Longboat’s military service during the First World War, referring to his participation as a dispatch carrier through the Western Front as his “wanderings in France” — as if they were a pleasant bohemian trek through idyllic landscapes.

When writing about Longboat’s wife, he described her “as fat as butter.” It was Marsh’s sly way of using sexualizing and degrading language that we know now is linked to the ongoing violence against Indigenous women and girls.

Marsh authored nearly seventy articles that either mention Longboat or provide stories that delve deeply into the man, his life, and his competitive performance. This is a significant body of work, considering that until the Second World War unattributed writers created most of what was found on Canadian sports pages, as well as most reporting generally. The Star printed many more columns about Longboat — ones with deeply racist messages — than are currently unattributed to Marsh.

This reminds us that both journalists and the powerful outlets they work for need to be held up to the light. We can do this by exploring and exposing historical narratives to see which ones are still circulating today, and by looking at these narratives in the larger context of the sports media industry to see what systemic changes are needed to support social change.

Breaking the cycle of abuse

Marsh left behind a massive journalistic legacy for all of us to wade through and unpack. He influenced generations of readers at home and abroad, schooling them about who was deserving of attention and what kind of attention they deserved.

He was also at the helm of cultivating a particular type of sports journalism in Canada, showing aspiring writers what types of narratives would land them a job. He aired common prejudices that enabled him to “connect” to his readers. In doing so, Marsh played an important role embedding systemic discrimination in Canada, with race relations being merely one aspect of his journalism.

It is important for us to consider how sports media has shaped, and continues to shape, the way we think about athletes and their contributions to sport. This will determine the kind of support we are willing to provide them as they perform for us and our nation.

If we see them as chattel, we are less likely to be interested in their welfare. If we see them as equals, engaged in unique and extraordinary service, we will be more likely to treat them with the respect they deserve.

Lou Marsh is not the idol many people thought him to be. But we still have much to learn from this man’s sporting legacy.

This article was co-authored by Brittany Reid, Adjunct Professor at Brock University, and Nancy Bouchier, Professor Emerita at McMaster University, with support from professors emeriti Ann Hall, University of Alberta; Bruce Kidd, University of Toronto; and Don Morrow, Western University.![]()

Janice Forsyth is a Professor at the School of Kinesiology at the University of British Columbia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()