Education in exile

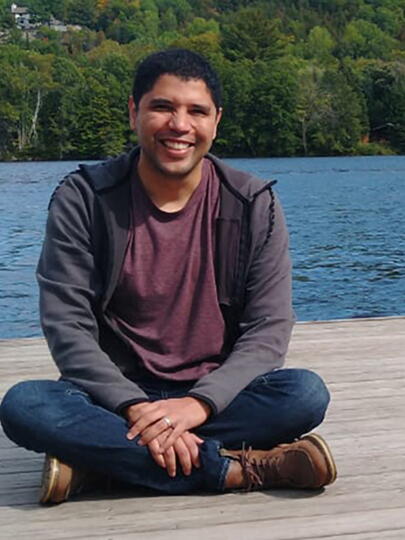

Lauryn Oates, PhD’12, went to Tajikistan to provide education for Afghans fleeing the Taliban.

A tumultuous downpour rained cold misery on the few dozen people who attended a Vancouver rally in support of Afghan women and girls, held just a few weeks after NATO’s withdrawal from Afghanistan.

The wretched weather matched an air of despondency among the crowd: it had been 52 days since secondary school girls in Afghanistan had been banned from attending classes by the Taliban. The rally, which was organized by the non-profit Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan (CW4WAfghan), was meant to be an outraged protest against the takeover of Kabul by the Taliban, whose core tenets include violence and the oppression of women. But despair, rather than anger, seemed to grip the sodden crowd.

“In many ways, I’m still in shock,” CW4WAfghan executive director Lauryn Oates told them. Since 2001, the West had sunk trillions of dollars into defending and rebuilding the failed state but in the end threw Afghanistan to the wolves, leaving the country with the impossible task of defending itself against the Pakistan-backed Taliban. It was a “foreign policy failure of epic magnitude,” said Oates, who is also a UBC adjunct professor. “I don't think I’ll ever get over my disappointment.”

CW4WAfghan is a non-profit organization with 10 chapters across Canada. Members have supported Afghan girls’ education rights since the late 1990s, when the Taliban reigned for five years until forced out by the West following 9/11. This horrific assault on American soil was masterminded by the militant Islamist terrorist group al-Qaeda, whose members had been given sanctuary in Afghanistan by the Taliban.

Since those early years, CW4WAfghan, which Oates joined as a teenager, has created schools in Afghanistan, trained 10,000 teachers, opened an orphanage, launched an online library, and educated two generations of citizens, male and female, across the country. Seeing billions in charity dollars, countless volunteer hours and expertise, and modern institutional infrastructures all vanish was a bitter pill to swallow. “My life’s work — is it gone?” Oates now muses. “I had those thoughts sometimes like, wow, what was the last 20 years for? I mean, not just for me, but the whole thing I was part of.”

Although Oates was angry that the international community allowed the Taliban to regain power, she wasn’t about to give up on her mission to provide education to Afghan girls and boys. A few months after the rally, she was in a hotel in Istanbul with her two young children, awaiting her husband’s arrival from Vancouver. Before going to Turkey, she’d spent the better part of two weeks in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan. In this tiny country, perched on Afghanistan’s northern border, she worked to bring a new CW4WAfghan-funded school nearer to completion. The facility, called Istiqlal, meaning “independence” in Farsi, will provide full-time instruction for hundreds of refugee children whose families fled the Taliban takeover.

Tajikistan has given refuge to about 15,000 Afghans and may yet uphold a 2021 promise to allow 100,000 more into the country. (According to the UN Refugee Agency, more than half a million Afghans are estimated to have fled since the Taliban takeover in August, adding to the 2.6 million who are registered as refugees abroad.) Many of those who arrived in Tajikistan have school-age children, who will have missed out on a year of education by the time Istiqlal opens in the town of Vahdat, half an hour east of Dushanbe. (Afghans who arrived in Tajikistan after 2014 have been forbidden to settle in the capital by a government cagey about an influx of refugees.)

Oates predicts that the Taliban will remain in power for years to come, imposing oppressive dictates upon a hapless population. Afghans, she says, will continue to flee, and must prepare for a permanent life outside their homeland.

English fluency and familiarity with a more globally oriented school curriculum is the best way to help Afghan students – and by extension their families – assimilate into a new country.

Many of the Afghan refugees currently in Vahdat are destined for Canada this year. To best prepare the children for a permanent future abroad, Istiqlal’s curriculum will include both French and English instruction. It is being modelled on the Toronto school system, embracing the arts, sciences, social sciences, and math. Instruction will also be given in Farsi as a bridge for those students not fluent in English or French.

This complicated undertaking is being organized by CW4WAfghan’s partner in Tajikistan, Jane Alliance Neighbourhood Services, a Toronto charity that supports immigrants and other vulnerable groups. The group’s executive director is Babur Mawladin. As an Afghan refugee in the 1990s in Tajikistan, Mawladin created a school, also named Istiqlal. This experience helped him lay the groundwork earlier this year for the creation of the new Istiqlal, by negotiating with the government to obtain permits and licenses, finding a building large enough to accommodate the school and a computer lab, and meeting with potential teachers and students. Families won’t be charged school fees, as they are generally impoverished, earning about $5 a day for 16 hours of labour and living in homes without running water or sanitation, he says.

Oates estimates that the school will accommodate at least 320 Grade 1-9 students, taught by 23 instructors who, on top of their teaching duties, will have to undergo training to become proficient in the Toronto curriculum.

Online learning will be incorporated into Istiqlal’s teaching system to allow Afghan children in other parts of the world – including Afghanistan – to partake in the classes. This “hybrid school” model will allow anyone anywhere in the world to connect virtually, says Oates. Since the completion rate for online classes is generally very low, Istiqulal will have special supports in place, including a synchronous teaching model that allows online learners to be just as engaged as students in the physical classroom as they work towards achieving recognized credentials.

One challenge is hardware: CW4WAfghan will have to get tablet computers and laptops to Afghan students around the world, since smartphone screens are too small for online courses. Connectivity is also required, which CW4WAfghan will bankroll, says Oates. Internet service providers in Afghanistan are fast and dependable, but there may come a time when the Taliban clamps down on them, necessitating satellite service to maintain Internet connection. “I envision a federation of schools – like Afghan schools in exile,” says Oates, looking to the Tibetan education model, which serves an uprooted diaspora. She also envisions future collaboration with top Afghan teachers and administrators who’ve fled the country and are now scattered around the globe. Such sharing of resources will help support Istiqlal well into the future, she says.

Students are waiting impatiently for school to open. Sixteen-year-old Oranos Sadat, who is hoping to immigrate to Canada with her family, says Istiqlal will bring her one step closer to “fulfilling our dreams.” Oranos eventually wants to study to be a lawyer like her father, who was a prosecutor in Afghanistan, sending Taliban members to jail for war crimes.

Sadat’s sister, Motahara, 14, aspires to become a doctor in Canada. She misses her friends in Afghanistan. “We don’t have a sense of community here,” Motahara says. “We don’t feel at home.”

The girls’ mom, Maryam Sadat, says it’s been difficult watching her children sit at home with nothing to do. “The children cry about not going to school. It’s very hard for a parent to see their child not be educated. We want to see our children be successful.”

Yalda Ahmadi, 18, says she is excited and happy to continue her education at Istiqlal. She made it to Grade 9 in Afghanistan before her family fled the rising violence. Ahmadi aspires to become an interpreter, if she and her family ever make it to Canada. (Last year, Canada pledged to take 40,000 Afghans, but by May 25 this year, the government had reported only 14,485 arrivals.)

Istiqlal’s principal is Malalai Jawad Hashmi, a former women’s rights activist who worked with the Afghan Women Business Federation in Kabul. She fled to Tajikistan with her family in late 2019 after four Taliban came to the house and threatened her life. Hashmi says about 700 kids in Vahdat should be attending school, and feels badly that Istiqlal can’t accept them all. “We will try our best to accept as many as our capacity allows.”

At this stage, Oates is hobbled by several factors preventing school expansion: building size, resources, and navigating registration requirements with the Tajikistan government. On top of this, Tajikistan is not the only place where Afghans live in limbo and require education services. Oates is using Istanbul as a base, because it is close to Tajikistan and many other countries hosting Afghan refugees. It also has a large Afghan refugee population with children in dire need of formal schooling as well as university.

CW4WAfghan will support Afghan women while the need is still there – until the Taliban finally fall. “They will ultimately fail,” says Oates. “They can’t be a complete pariah in the international community. Afghans won’t tolerate it. That’s why they’re leaving in droves. The Taliban is draining the country of all its human capital because of their policies. Sooner or later, they’ll collapse.”