Dreams fulfilled: A B.C. Internment survivor leaves a legacy

A 90-year-old internee, who overcame hardships to achieve his education and career goals, created a memorial to teach others about the Japanese-Canadian experience.

Almost no one blinks an eye at the fact that the president of UBC for the past six years has been a person of Japanese descent. Yet having Santa Ono, who will leave UBC in October, as the head of our university marks a historical turnaround for a region that would have once designated him as an “enemy alien” — based upon his ethnic identity.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the exclusion of Japanese Canadians from a 100-mile zone along the British Columbian coast during the Second World War. The uprooting, conducted in violation of Canadian citizenship rights, had irrevocable impacts upon lives, communities, and subsequent generations.

Among those affected was UBC alum Dr. Aki Horii (BA’55, MD’60).

In an interview at the Robert H. Lee Alumni Centre, the now 90-year-old Internment survivor and retired family doctor expresses delight about the Vancouver-born Ono having helmed his alma mater.

“I think it’s wonderful. Wonderful!” Dr. Horii says. “I’m very proud of his heritage.”

That Dr. Horii was able to attend UBC, let alone become a medical doctor, is impressive in itself, considering the challenges he faced in pursuing post-secondary education. What his life story illustrates is how a spirit of perseverance can help anyone overcome hardships and reach their goals — no matter how impossible they may seem.

A life forever altered

When war broke out in the Pacific and Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, Aki Horii was a 10-year-old student in Grade 5, one of 630 nikkei (emigrants of Japanese descent) children at Lord Strathcona Elementary School. Although he was born in Vancouver in 1931 and grew up in Paueru-gai (the Vancouver neighbourhood known in English as Japantown), he was part of the demographic group considered a threat to national security. This, despite the RCMP and Canadian Army and Navy not finding any evidence of sabotage or military threat from Japanese Canadians.

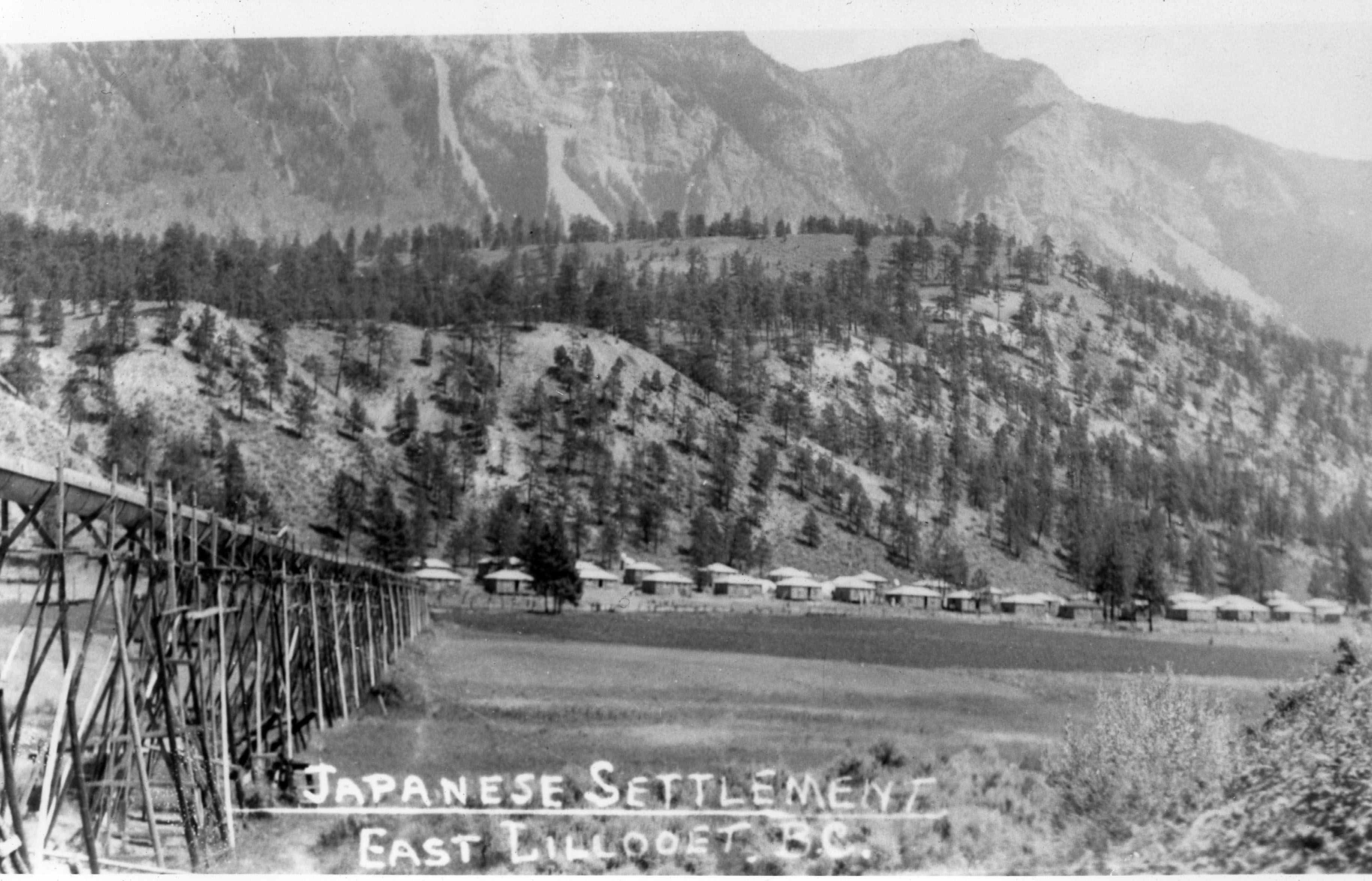

Forced to relocate to the B.C. Interior in 1942 under the War Measures Act, his family moved to East Lillooet, located outside of the town of Lillooet. It was a “shock” to him what little luggage they were permitted to take with them from their Vancouver home. He calls East Lillooet, still under construction when they arrived, “one of the worst internment camps” where they faced “very harsh” living conditions.

“I was naïve thinking that ‘Oh, it won't be too bad living in this little town called Lillooet,’” he says.

His family, he explains, had to pay for and build a tar-paper shack without electricity or running water to live in, and grow their own vegetables. (Indigenous people, he says, rode horseback through the mountains to sneak salmon to them.)

Education was equally makeshift. Internees built a two-room schoolhouse for Grades 1 to 8. Without any qualified teachers available, the young Aki was taught by those in the camp who had high-school diplomas. Although Japanese Canadians were originally forbidden from entering the town proper, the discriminatory rules eventually relaxed, which enabled him to attend the local high school.

Although Japan surrendered and the war ended in 1945, wartime restrictions on Japanese Canadians weren’t lifted until 1949. In fact, when all Japanese Canadians were forced to either move east of the Rockies or be deported, about 4,000 individuals were sent to Japan in 1946. Almost all nikkei properties and possessions had been sold off by the government, leaving those remaining in Canada to rebuild their lives with whatever they had managed to keep.

Making the grade

When Aki graduated from high school in 1949 and was finally able to return to the coast, his parents sent him to attend UBC. He commuted to school from a Dunbar boarding house via streetcar — and racism remained commonplace in the city. Despite being daunted by the whole prospect, he discovered he had what it took to succeed academically.

“I was flabbergasted I got good marks,” he says.

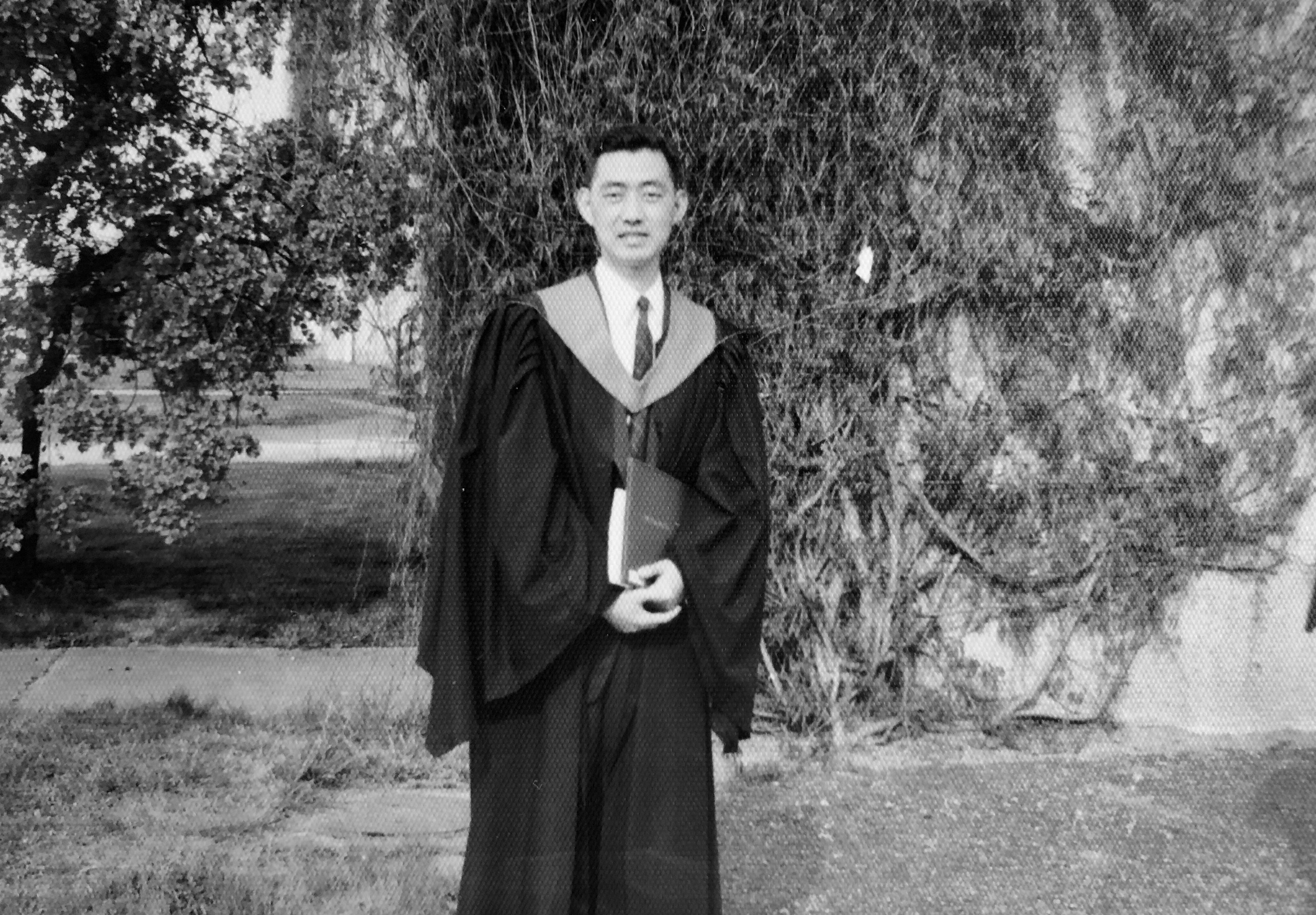

As his family was still re-establishing themselves financially, he took two years out of school to work as a fisherman to help make money for them. After resuming his studies, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Zoology in 1955 (the degree was within the Faculty of Arts at the time). Unfortunately, he missed his convocation in Vancouver because he didn’t have enough money to return from working in Prince Rupert.

Although he couldn’t afford tuition for medical school, he applied anyway and was one of the 60 students accepted out of 450 applicants. Dean Walter Gage, who was the Dean of Inter-Faculty Affairs at the time, helped with bursary funds.

“I never forgot the kindness of Dean Gage,” Dr. Horii says. Without a bank account, he would do whatever he could to save money, he adds, even hitchhiking to school instead of paying 10 cents for streetcar fare. After surviving a near-death experience from a ruptured appendix, he graduated in May 1960.

“One of my proudest moments was to have my picture taken,” he says of his convocation in 1960.

After an internship at Toronto Western Hospital, he launched his family practice in Vancouver in 1961. Having learned the Japanese language while attending the Vancouver Japanese Language School as a child, he focused on helping issei (first generation) patients who often could only communicate in Japanese. Dr. Horii continued his family practice for almost half a century — he semi-retired in 2002, and fully retired at age 78 in 2009.

He’s remained a lifelong supporter of education. He has sponsored field trips to Stanley Park and the Vancouver Aquarium for underprivileged and immigrant children for the past 25 years, has conducted talks about his internment experience at schools to over 2,000 students, and donates books to the schools he visits.

Redress and reconciliation

Unlike Dr. Horii, however, other nikkei weren’t able to complete their education. The forced relocation disrupted the lives of 76 UBC students who missed their graduation ceremonies or couldn’t finish their studies.

Although Japanese Americans were also interned, U.S. universities had protested the relocation of Japanese American students and made special arrangements for the students to complete their education. That wasn’t the case in Canada. In fact, there were only two voices from UBC in defense of the nikkei students: economics professor Henry Angus and commerce professor E. H. Morrow.

In recent decades, retired high-school teacher Mary Kitagawa launched a campaign to request UBC to grant honorary degrees to these students. Her proposal in 2008 was initially rejected but, ultimately, UBC awarded those students honorary degrees — 22 were still alive, and family members were invited to accept on behalf of those who had since died. A tear-jerking ceremony was held in May 2012 to honour them. (Kitagawa herself received an honorary degree in 2020.)

UBC also committed to further reconciliatory efforts. That same year, UBC launched the 1942 Japanese Canadian Students Fund to support research in the Asian Canadian and Asian Migration Studies program (which began in 2014), as a tribute to the students. In addition, the UBC Library undertook a project to collect and archive the stories of individual students. Some of the oral histories were used to create the film “A Degree of Justice: Japanese Canadian UBC Students of 1942.” Furthermore, the library also began digitizing the Tairiku Nippō newspaper, which was published from the early 1900s to 1941.

At the federal level, the Canadian government officially apologized for the Internment in 1988 and provided symbolic redress payments to survivors and community funds. But it wasn’t until 2012 when the B.C. government publicly apologized, followed by a formal apology from the City of Vancouver in 2013.

Although almost 22,000 individuals were interned, only about 6,000 survivors remain alive today. Yet community members are continuing to carry on the long journey to justice.

A dream realized

Those efforts continue to result in new developments.

In response to a proposal in 2021 from the National Association of Japanese Canadians (which is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year), the B.C. government announced a $100-million initiative for Japanese-Canadian communities on May 21 — the same date as the first arrivals in the province’s internment camps eight decades ago. The initiative includes funding for health and wellness programs for survivors; creating and restoring heritage sites in B.C.; and updating B.C.’s curriculum to teach future generations about the Internment.

Among the heritage site projects that were chosen to receive funding was one that Dr. Horii conceived: the East Lillooet Memorial Garden. Dr. Horii — who was among the speakers at the provincial government announcement three years earlier — came up with the idea for the memorial in 2015.

“I had a dream that before I left this planet, I would like to see some sort of memorial to honour and commemorate our parents and the older nisei (second generation) who suffered so much hardship, hard work, and injustices that were forced upon them by racist politicians and the government,” he says.

Built on an infill over an old highway, the garden was first completed in 2018. As the original garden faced maintenance challenges and became overgrown with weeds, a committee decided to transform it into a Japanese rock garden. The garden now features gravel, rock islands, and a rock waterfall; a mini bridge; a stone monument; a history sign; and an arbour (which overlooks the site of the original camp). Seven pine trees were planted, one for each year of the Internment. A renewal opening was held on May 7.

“We want the history to be remembered by everybody, especially the young people,” Dr. Horii says. “Most of the residents living there now were born post-war and they don’t even know that there was an internment camp across the river.”

Also marking the 80th anniversary of the Internment, reunions and cultural events were held this summer and will continue into autumn at former internment sites (such as Greenwood, Kaslo, and Tashme) and the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre in Burnaby.

As a new school year gets underway, Dr. Horii, who is a “hard believer” in the Japanese expression ganbare (“hang in there and don’t give up”), also has a message for students, recent grads, and all alumni.

“If you have a goal in mind — and it doesn’t matter how long it takes,” he says, “if you persevere, you will attain your goal.”