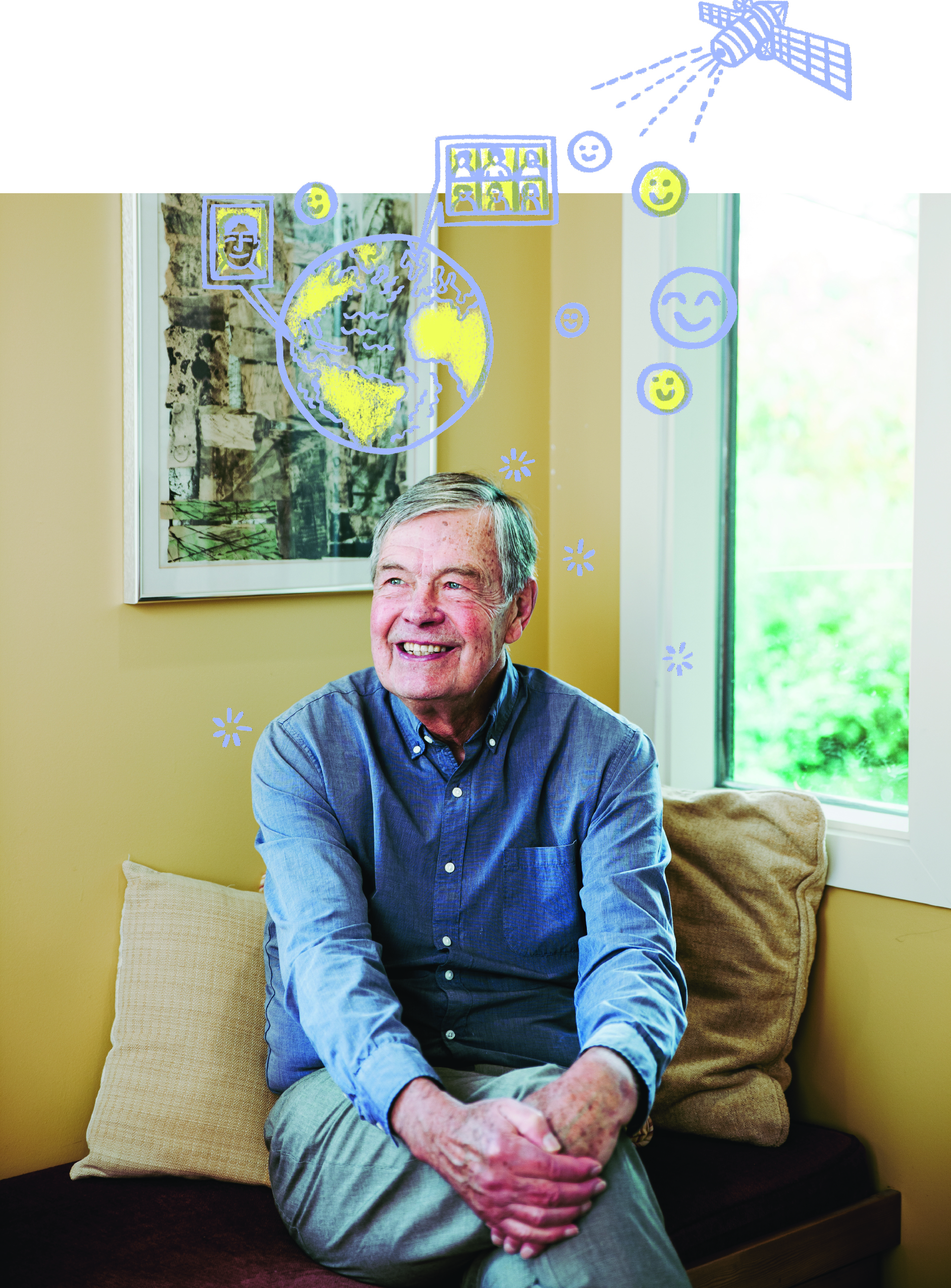

Professor John Helliwell. Illustrations by Nina Chakrabarti and photography by Anita Lee.

Job satisfaction and the COVID effect

COVID forced an abrupt change to the daily working lives of millions. In terms of our well-being, are we worse or better off for it?

It should come as no surprise that The Happiness Guy thinks the world of work might actually get better thanks to the lessons we’ve all learned from COVID-19. After all, John Helliwell seems resolutely positive about nearly everything; why wouldn’t he find the bright side in a pandemic?

But Helliwell is no thoughtless Pollyanna. He’s built a remarkable career by proving his happy hypotheses, so if he’s recommending optimism, it wouldn’t hurt to give him the benefit of the doubt. Research shows that just embracing his sunny view will make you happier in the meantime – even if things don’t turn out for the best.

Helliwell is an emeritus professor in UBC’s Vancouver School of Economics, a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, and co-editor of the World Happiness Report. Looking at his résumé, you can’t imagine he’s had a spare minute to indulge in idle pleasure, and yet we’ve been told that all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. Then again, Helliwell’s fellowships, honours, and awards perhaps suggest that hard work is precisely what makes him happy. From the Rhodes Scholarship to the Order of Canada (Officer!), he’s had every manner of academic and social recognition.

The man himself would tell you that effort and well-being are, at the very least, highly correlated. You don’t get happy by pursuing happiness; that’s a trap. For example, Helliwell says the research shows that giving to charitable causes will increase your level of happiness – but only if you do so for its own sake. If you donate specifically because you hope it will make you happy, it doesn’t work.

But work makes you happy. As reported in the most recent edition of the World Happiness Report (in the chapter “Work and Well-being during COVID-19: Impact, Inequalities, Resilience, and the Future of Work”), “One of the most robust and well-documented findings in the economics of subjective well-being is that the unemployed are significantly less happy than the employed.” And it’s not about the money (or not all about the money). Respondents in a major US study reported that their biggest happiness driver at work was having a sense of belonging, which they said was more than three times as important as being fairly paid.

That might lead you to think that the pandemic should have been a downer, as so many employers’ first reaction was to send their workers home, where they were physically isolated and subjected to endless mind-numbing Zoom calls instead of enjoying actual human interaction. But Helliwell isn’t having it.

First, as becomes obvious when we begin our interview with quick commentary about our relative workspaces, he’s a big Zoom fan. “This is so much better than the telephone,” he says. Having spent decades flying around the world, meeting with others in the top tier of happiness researchers, he was delighted to connect instead from the off-grid beauty of his family’s bit of Hornby Island during the first year of COVID, and now from their Vancouver home in the rainy months. He also gets to meet more regularly and easily with a host of different people. For example, there is a new weekly happiness seminar at Oxford University that he previously would have been able to attend only infrequently – and in a jet-lagged state. Now, he can attend regularly, meeting with new young scholars and senior ones from Oxford and around the world.

Zoom also gives his work a wonderful sense of immediacy that was lacking before. For example, if he has a revelation about a joint project, “we are delighted to be able to hash this out together when the idea is fresh, not at a conference 10 months out.”

In triggering what Helliwell calls “the astonishing pivot to virtual,” COVID also delivered a lot of people from the costly and time-consuming process of travelling back and forth for work. “Often,” he understates, “the commute is not a place to generate happiness.” And yet commute we did, thanks to what Helliwell calls “an overemphasis on where people live and what they earn – something that made them travel further and further for a bigger home.

“COVID broke that link.”

Some people may never return to an office, which means they can go even further to find a home that is both affordable and, by other measures, happiness inducing. Others may downsize to move closer. But either way, Helliwell says, “the future will never be quite the same. And a lot of people – net/net – will be better off.”

But some won’t. The Happiness Report chapter points out that, despite its immediate benefits, the liberating shift to a distributed workforce model could also do some harm in the long term. It states: “For workers, social and intellectual capital is built by shared experiences with co-workers and unplanned social interactions that broaden one’s thinking.” As well, “Building meaningful relationships with co-workers, especially management, is critical to job and life satisfaction. Working from home all the time does not allow for that to the same extent as the office.”

Another issue, at work and in other contexts, is trust. Helliwell says it’s easier to settle disagreements or resolve difficult issues if you feel you can trust the other parties. And trust is most easily built face to face.

Even now – even for Helliwell – there have been aspects of the COVID crisis that have directly undermined people’s well-being. Some of those who lost their jobs altogether found themselves facing economic insecurity for the first time, undermining the confidence they might once have felt to pursue work that was meaningful ahead of a job that is financially rewarding. In response, the Happiness Report piece speculates that some stubborn optimists might still search for employment that provides meaning and a strong social network, “while others may begin to prioritize earnings and job security.”

For either group, Helliwell says it pays to remember that happiness can be a matter of attitude or expectation. He has two favourite illustrations, both rooted in real-world research. The first, touching on the matter of attitude, arises in two of the most common traffic interactions. If someone gives you the finger when you’re driving, both parties wind up unhappy, whereas if someone waves to let you in, it winds up being a nice moment all around. It didn’t cost anyone anything, and yet there was still a happiness dividend.

As for the power of positive expectations, there are international studies on what happens to dropped wallets. The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is that in every jurisdiction most are returned, cash intact. Helliwell says that when they did the first experiment in Finland, 10 out of 10 wallets were returned. That’s not what people expect, but when they hear about it – when they refocus on all the honest people instead of obsessing about the thieves in the news – they’re inclined to feel better about their community, their neighbours, and themselves.

So, Helliwell concludes, whether it’s work or anything else, “I tend to be optimistic about these things. I cherish the positives and put the negatives in the drawer.”

It seems like an example worth following. Then, even if you do lose your wallet – or your job – you can still be cheerful in the meantime.