The UBC Entrepreneurship Engine

How an MBA grad was equipped to potentially change the lives of millions.

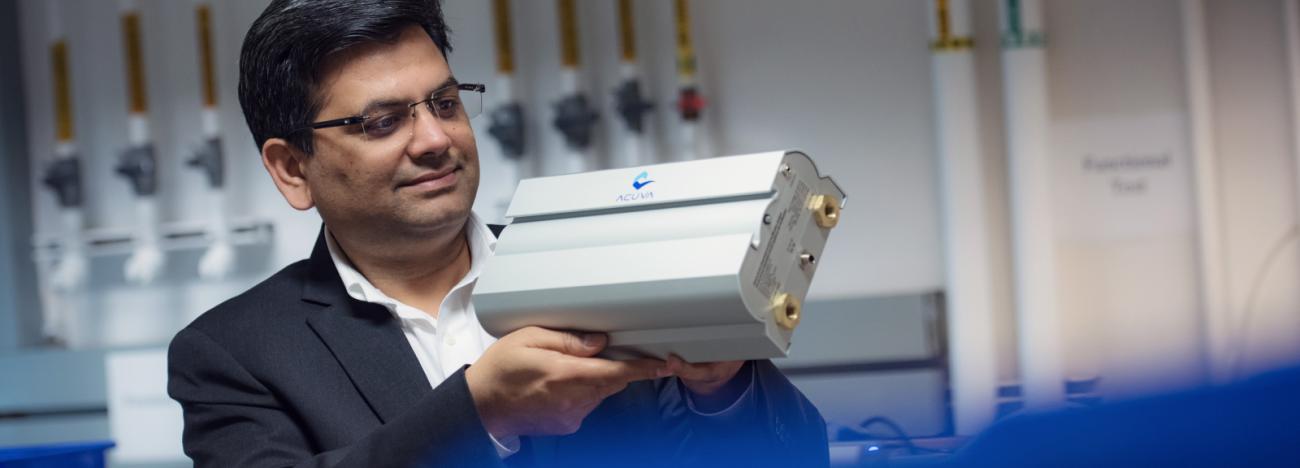

When Manoj Singh, MBA’10, set out to launch a startup, he didn’t just want to create a successful business – he wanted to help change the world.

Singh had already studied engineering at one of India’s most prestigious institutes and worked for over a decade in research and development with the Tata Group, a $120-billion enterprise that operates in 100 countries. He had also worked as head of market development and technology commercialization for South Asian markets at Westport, an engineering company that specializes in alternative fuels and operates in more than 70 countries.

THE VENTURE

But deep down Singh was an entrepreneur with a passion for startups and the steely mix of knowledge and nerve required to succeed – and he was willing to put his life savings on the line to do it.

A couple of years after completing his MBA, Singh returned to UBC to in search of collaborators to start a new enterprise. He approached entrepreneurship@UBC (e@UBC), which offers mentorship, venture creation and seed funding, and helps connect businesspeople with research and innovation on campus. They in turn linked him with the University‑Industry Liaison Office, where Singh learned about the technology that would drive his company – Acuva Technologies Inc.

The technology – which was developed by Dr. Fariborz Taghipour of UBC’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering – uses ultraviolet LED to destroy microorganisms in water, but what really sets it apart from other purification systems is that it requires very little power – so little, in fact, that it can operate on battery alone. It’s also portable, compact, requires virtually no maintenance, and it doesn’t create waste or harm the environment.

“This is independent of grid infrastructure, which means you can deploy it wherever you want,” says Singh, who adds that the technology is especially promising for the many areas of Asia and Africa where access to power is one of the biggest barriers to clean drinking water. “And once you install it, it works an entire lifetime without having to do anything more.”

THE MOTIVATION

But for Singh it the motivation wasn’t only to create an environmentally and financially sustainable business model – he was also driven by personal experience.

“I spent the first 15 years of my life in rural India, and have gone through the challenges of accessing clean drinking water, and infrastructure issues. All those things you read in textbooks, I have experienced them myself,” says Singh, who weaves social responsibility into all of his business pursuits.

Todd Farrell manages the UBC Seed Fund, which invests risk capital in innovative startups founded at UBC. He has worked closely with Singh from the beginning and oversaw initial funding of $450,000 for the project. He says Singh’s blend of business knowledge and technical skill, along with his calm demeanor and excellent interpersonal skills, have been invaluable.

“He’s also a very tenacious individual – and he is willing to ask for help, but he certainly has his own mind. He collects information, analyzes what he hears, discards what he doesn’t like and comes up with a plan,” says Farrell, who adds that Acuva will not require philanthropic support from governments or charities, but rather is projected to be profitable on its own.

Benefiting from two seed rounds and a bridge, Acuva evolved from a research project and pre-prototype to a commercial project in less than 24 months. “That’s a pretty incredible pace,” says Farrell, who now chairs the company’s board.

Acuva went on to attract a Series A round of funding from other investors, and to date has raised $4.5 million, with the majority of funds coming from local angel investors who are alumni of UBC.

THE STRATEGY

Singh plans to keep up the pace, and hopes that within a year the product will be developed to the point where it can be shipped to off-grid areas in China, India and other areas of Asia and Africa.

Eventually the technology will also be used to kill microorganisms in the air and on surfaces. But to start, the company launched the product in North America, and geared it toward the recreational market – boaters, campers, RVers, and others who may not always have access to clean water when they go off the beaten track.

“We decided to start in North America primarily because of physical proximity,” says Singh. “It’s much easier to troubleshoot when your customers are next door, rather than 10,000 kilometres away.”

The technology has since been developed into cost-effective water purification units for mass markets, intended for integration into appliances such as ice-makers. Six months from now, the water dispenser in your fridge may well be using Acuva technology.

Today, the company employs 20 people and has formed important partnerships with global distributors. As markets expand and the rate of production ramps up, the product cost has dropped dramatically and is predicted to drop even further, boding well for the future provision of low‑cost units to remote communities.

THE UBC ADVANTAGE

Singh says he has used “every bit” of the knowledge he acquired during his MBA to make Acuva a success, and he also credits e@UBC, the University-Industry Liaison Office, and all of the entrepreneurial support at UBC for helping to get his business off the ground.

As well as the seed-funding, use of office space, and the technology itself, Singh benefited from a dynamic network – from which he drew for mentorship, investment and talent – including the three UBC PhD grads he hired to join the company.

“When you start a small company, especially with technology, you start with almost zero – no credentials, no identity, nothing to show. It’s very hard to find the first set of people who believe in what you believe, who associate their prestige and reputation, and who put in the resources and money,” says Singh. “That was a huge help that Acuva received from the UBC ecosystem.”

Singh says all of that knowledge and support, along with his 20 years of corporate experience, have given him immense confidence, and a desire, in turn, to help his team members pursue their dreams. His upbringing and his experience as an immigrant also gave him an unshakable tolerance for risk.

“In the early part of my childhood I had nothing to lose. That made me an inherent risk‑taker. Once you have that attitude, everything becomes easier,” he says. “You have the ability to make decisions that are inherently risky for many – because for me, it’s very normal.”