Precious Resources

In August 2014, the tailings pond at the Mount Polley mine site failed, spilling millions of litres of highly polluted mining waste into Polley Lake and raising the level by 1.5 metres. The slurry continued its path through Hazeltine Creek, expanding it from two metres wide to more than 50, and on into Quesnel Lake and Cariboo River. It was called one of the biggest environmental disasters in modern Canadian history and will continue to have a devastating impact on the area for decades to come. For Nathan Skubovius, a member of the Tahltan First Nation, it was also a personal turning point.

“I knew that Imperial Metals, the company that was responsible for that disaster, was the same company that was building the Red Chris mine in the centre of the Tahltan territory,” says Skubovius, who would go on to study mining engineering at UBC. “It was a big shift for me to understand how mining can go in the wrong direction. I realized that if I was going to do anything to change things, I needed to use my education.”

Skubovius didn’t grow up in the Tahltan territory, but spent many summers there with his grandfather learning about his traditions and the Tahltan way of life. He developed a strong bond with the territory and knew, at some point, that he would do something for his people to help sustain his ancestral land.

“I’ve always been a bit of a doer,” he says. “And I’m not the kind of person who stands by and lets things just happen.”

His enthusiasm during those summer visits drew the attention of the Tahltan Central Government (TCG). When he entered UBC in 2015, the TCG asked him to be a representative on the Tahltan Youth Council. In 2017 he was hired as the Land Use Planning co‑ordinator and led focus groups on different aspects of development in the territory. The TCG has a long history of activism in promoting traditional values while embracing the demands of modern industry. In 1987, it established a resource development policy that declared the territory open for business, and outlined the restrictions and regulations that needed to be met before development could happen.

The TCG also championed the idea of re‑establishing long‑neglected nomadic trails and getting Tahltan youth involved and interested in their ancestral traditions. As youth leader, Skubovius was tapped to organize a group of young people to help build a footbridge – designed by his father – at a traditional crossing, and that experience started the idea that would eventually manifest itself as the Tene Mehodihi (“The Trail We Know”) project. He saw it as a way to educate Tahltan youth in their own culture and give them some insight into the opportunities that awaited them in the development of the Tahltan lands. It would expose students to traditional and modern survival skills and, at the same time, introduce them to the technical skills they would need to work in the resource industry.

“We can no longer fight with bows or arrows or knives strapped to our hands. We must fight with education.”

– John Carlick, Tahltan Ancestor

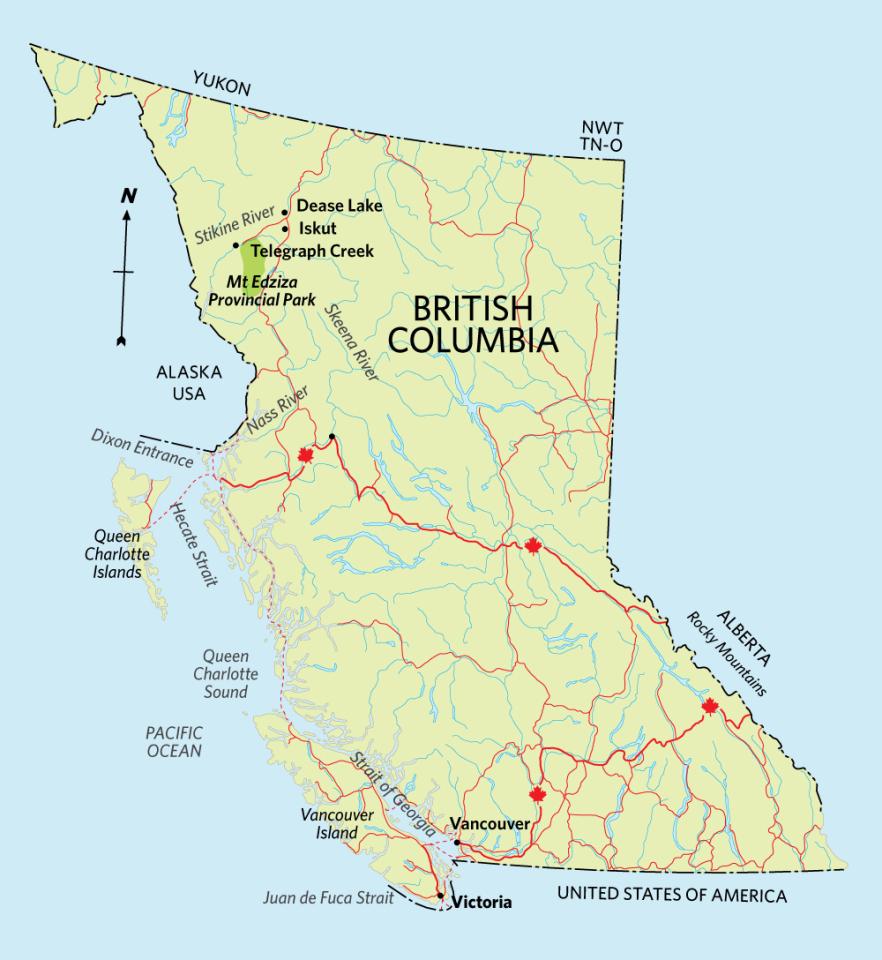

Development in the Tahltan lands is, as is the case in many First Nations, controversial. Focused largely on gold, copper and natural gas, resource development places huge and sometimes extremely damaging demands on the land. Memories of the various gold rushes of the 1800s don’t die easily, and there have been some projects in resource‑rich First Nations territories that have ignored local concerns. Others, like the Mount Polley mine, have been disastrous. In 2012, a methane fracking exploration project slated for the headwaters of the Skeena, Stikine and Nass rivers – an area called the Kablona that is considered sacred by the Tahltan nation – was halted due to protests by the Kablona Keepers, a group of Tahltan elders. The Kablona Keepers have protested a number of exploratory operations over the years, though they don’t condemn development per se. In an interview with the Globe and Mail at the time, the group’s spokesperson, Rhoda Quock, was quoted as saying, “I don’t want people to get the impression we’re against all development. We’re not. But these places are sacred and need to be preserved.”

Christine Creyke, lands director for the TCG, thinks that development, properly managed, can be a benefit to all. “The Tahltan Nation is industry supportive,” says Creyke, who has signed agreements with resource companies that provide significant returns to the community. “Our agreements with industry help support all the work we do in sustaining and building our community.”

Skubovius echoes these perspectives. “We’re not against development,” he says, “it’s just where, when, at what pace and to whose benefit. These are the serious questions that project managers have to consider. We have locations identified – grave sites, sacred sites, village sites – and when projects come in without considering those things, they won’t go ahead.”

One of the prime considerations Skubovius has for development projects is the employment prospects for Indigenous workers. “Mining jobs of the future aren’t going to involve heavy labour or machine operation,” he says. “What we need are more electricians, more managers, more project designers. There’s a big shift in job opportunities. And that means more education for our workers.”

Which is where the Tene Mehodihi project comes in. Skubovius’ idea was to create adventure hikes for Tahltan youth that show them the importance of their traditions and include strong educational components. By showing students the richness of their traditions, and tying that in with the opportunities that await them, Skubovius hopes to encourage Tahltan youth to stay in the territories.

“One of our biggest issues in the Tahltan territory,” says Creyke, “is the retention of our people. Right now, 85 percent of our members live outside the territory. In 10 years, it may climb to 95 percent. Nathan’s idea fits really well with our overall goal as a nation to retain our youth and encourage others to move back to the territory.”

The Tahltan were originally a nomadic people who over the centuries followed caribou herds along well‑worn routes. Most of these routes have, in the recent past, fallen into disuse and become overgrown. One of the first activities, building the footbridge, was followed by the TCG sponsoring a cleanup of a trail that runs past Buckley Lake, skirts the Mount Edziza volcano and ends up in Telegraph Creek. In the summer of 2018, that trail was used for the first hike of the Tene Mehodihi project.

The hike involves two different facets. Firstly, with the help of elders who join the hike at Buckley Lake, students learn how their ancestors used the land, how they travelled and how they lived. They also learn about traditional Tahltan crafts, food preparation and art.

The second aspect of the hike is where UBC comes in. Students are introduced to navigation and bush skills and visit a mining exploration camp that was set up by a mining concern to investigate the potential for resource development nearby. Using the resources of the camp and those of UBC participants, students learn how to use various instruments to test plants, take water and soil samples (and properly document them), analyse rocks, and perform water management tasks. It helps give the students an insight into the intricacies of the development process and, hopefully, stimulates their interest in learning more. Last summer’s hike was to take seven days, though it was cut short by a day because of the wildfires that raged through Telegraph Creek.

Nadja Kunz, assistant professor with the UBC School of Public Policy and Global Affairs and the Norman B. Keevil Institute of Mining Engineering, was part of that hike.

“I’m interested in the social and environmental issues around mining,” she says, “as well as the engineering challenges. Participating in the hike was a great way to involve the students in the physical aspects of mining development, but also in how that development impacts the land.”

During the hike, Professor Kunz, who is Canada Research Chair in Mine Water Management and Stewardship, brought water sampling equipment along to show students how water monitoring works, and introduced them to the kind of equipment and analysis they could expect to encounter in a university setting.

“Having UBC professors involved in research projects is a big part of the program,” says Skubovius. “They help students understand the processes that have an impact on development and sustainability. UBC’s standards are world class, so when our students experience these projects and conduct these experiments, they’re doing it with instruments and instruction of the highest calibre.”

And, coupled with traditional instruction, students will see the connection between sustainability and development. “Tahltan culture is about being efficient on the land,” says Skubovius, “whether it’s how to use the landscape – ridgelines, peaks, other high points as guidelines to travel – or how to harvest food in the wilderness, not wasting precious resources and understanding what you need to survive. It’s a good mix.”

“Tahltan culture is about being efficient on the land, whether it’s how to use the landscape – ridgelines, peaks, other high points as guidelines to travel – or how to harvest food in the wilderness, not wasting precious resources and understanding what you need to survive. It’s a good mix.”

This summer, Skubovius plans two hikes. The first, mirroring the 2018 adventure, will involve 14 to 16 year‑old‑students, with supplies and equipment brought along on pack horses. The second, with older students, will have students packing in their own gear to hike around the western edge of the Mt. Edziza plateau. They will meet up with the younger students at Eve’s Cone, one of the cinder cones on the flank of Mount Edziza.

Skubovius’ long term plan is to expand the Tene Mehodihi project to include five different adventures running through the summer, with students able to acquire industry‑valid certification – such as First Aid, water and avalanche rescue – that can be built into the high school curriculum.

Skubovius’ plans after gradudation aren’t set in stone just yet. He will spend this summer managing the Tene Mehodihi project, working out the bugs and planting the seeds for the project’s future. Then, he sees a PEng in his future, and perhaps an engineering job with an international mining company. But his vision for Tene Menodihi is long‑term.

“We’re building the model,” he says, “and we need to figure out what’s gone wrong, what’s gone right. We need to understand the steps it’s taken to get to this spot. Then, I hope, we can share this program with other mining communities.

“We’re building the model, and we need to figure out what’s gone wrong, what’s gone right. We need to understand the steps it’s taken to get to this spot. Then, I hope, we can share this program with other mining communities.”

“We have a long history of mining in the Tahltan territory, and we’ll have a long future in mining. We’re a resource rich area. We’re going to have large-scale industry for years to come, and I know the big companies are bringing autonomous equipment to these sites, which will mean huge job losses for our communities. If we can train the next generations to take on the higher‑level occupations, and to not be equipment operators, we’ll be very successful in the industries, and in sustaining the land.”

Avoiding future Mount Polley disasters will take a combination of will, knowledge, dedication, an unbreakable bond with the land and an understanding of its significance to traditional culture. Nathan Skubovius and the new generation of First Nations leaders will see to that.