Colonized: The Human Microbiome

I’m sitting on an airplane 34,000 feet over the Pacific, reading an advanced copy of Brett and Jessica Finlay’s new book The Whole‑Body Microbiome on my cellphone, and all I can think is: “Catastrophe!”

It’s not that I’m worried about falling from the sky. No, the disaster I fear is internal. The Finlays’ book is a love letter to the billions and trillions of microbes that colonize our bodies and collaborate in everything from keeping our breath fresh to helping to harvest macronutrients in our lower intestines. The authors argue, convincingly, that the health of that entire bacterial community – your personal microbiome – is one of the great predictors of a long and happy life. Yet, 48 hours before being assigned this story, I had begun a course of antibiotics to conquer a lingering case of strep throat. I was about to devastate my whole microbial team. As I said: Catastrophe!

The good news, which unfolded in the pages of their book and in later conversations with father, Brett, and daughter, Jessica, is that The Whole‑Body Microbiome is also a how‑to manual for aging in good health, hand‑in‑hand with the microscopic creatures that float from your throat to your – well, just about everywhere. And, if you were looking for a tour through the microbiome crossed with a guidebook for healthy living, you could hardly do better than recruiting the Finlay team.

Microbiology buffs – or just longstanding UBC fans – will recognize the name Brett Finlay. The late Nobel laureate Michael Smith recruited Finlay to UBC in 1989. An Edmonton native, Finlay had done an honours BSc and a PhD in biochemistry at the University of Alberta and then gone on to do a post‑doc in microbiology at Stanford University in California. Smith, who had a sharp eye for talent, recognized a brilliant and innovative researcher and somehow managed to outbid offers that Finlay had from powerhouse competitors including Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Smith’s judgment was surely borne out. Finlay, 60, has held the UBC Peter Wall Distinguished Professorship since 2002, and he has indeed distinguished himself in every imaginable way. He has published more than 500 peer‑reviewed journal articles and, as a principal or co‑investigator, attracted more than $100 million in research funding from sources including the provincial and federal governments, private sector companies, and international funders such as the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. His largest current project is based on a $4.6 million grant from Genome BC for the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) Study on childhood asthma and the microbiome. Finlay’s list of awards and distinctions runs to four pages and ranges from the Orders of British Columbia and Canada (as an Officer) to prizes including the Killam and the Galien. Really, it would be easier to list the prizes that he hasn’t won – yet – but you wouldn’t want to jinx it.

Finlay’s writing partner for this book is daughter Jessica, 30, an environmental gerontologist who is clearly determined to keep up the family standard. She did a BA and BEd at Queen’s University, before switching to geography and gerontology for a master’s and PhD at the University of Minnesota. She’s currently doing a post‑doc at the University of Michigan, studying environmental effects on cognitive decline – and particularly the effects of the built environment.

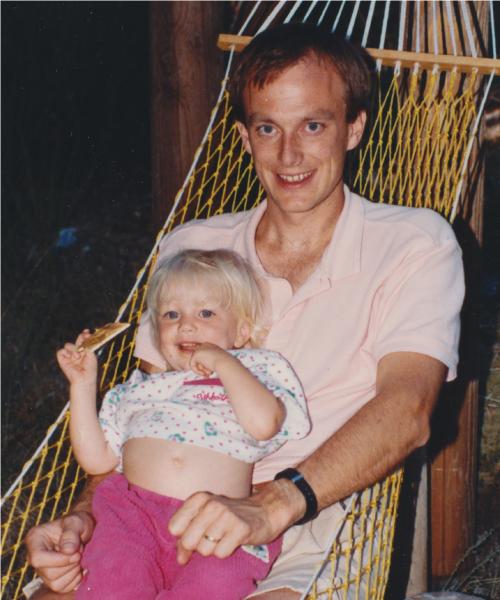

A couple of years ago, Jessica and her father were out for a run together in Maui, and they were talking about his last book, Let Them Eat Dirt: Saving Your Child from an Oversanitized World. This, also, was a guidebook on microbiota. As Brett Finlay says, “The first 1,000 days of life are just so important,” and one of the big tasks for children is building a diverse, healthy and robust microbiome – a process that starts early. He says: “The first and best birthday present” we receive comes in the form of the vaginal and fecal microbes that babies ingest and collect on their journey down the birthing canal, as demonstrated by the fact that babies born by Caesarian section are at 25 per cent higher risk of asthma, obesity and diabetes. Finlay, and his co‑author on that book, Dr. Marie‑Claire Arrieta – a former post‑doctoral student of his and currently a University of Calgary medical professor – explored this and other ground‑breaking research, along the way urging parents to let their little ones pet the dog, crawl in the mud and (again!) avoid antibiotics unless they’re absolutely necessary.

But during the run, Jessica complained that Let Them Eat Dirt spoke only of the experience of children from birth to 12 years. What about the rest of us? So father and daughter set off on a two‑year project to review and report on more than 1,000 research papers in this fast‑breaking field to help us all understand better how to manage our microbiome for the later parts of our lives.

Microbes are crucial to our day‑to‑day health and implicated in everything from cardiovascular diseases to depression.

As Brett Finlay knew it would, the search turned up some amazing revelations. Microbes are crucial to our day‑to‑day health and implicated in everything from cardiovascular diseases to depression. For example, if you don’t brush and floss adequately, pathogenic microbes in your mouth can break through damaged gums and into your bloodstream, later causing inflammation and tissue damage in your arteries and heart valves. Misfolded proteins in the gut (triggered by an altered microbiome) can make their way up the vagus nerve and into the brain, where they can cause plaque build‑up that is similar to that seen in Alzheimer’s patients. Gut bacteria are also implicated – or at least useful as a predictor – in Parkinson’s disease.

On the bright side, the book is full of these kinds of “Say what!?” discoveries. More frustrating is the fact that everything is so new that the medical innovations and treatments that might arise are not yet available or are in their earliest stages. For example, one of the microbes we don’t want is called Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), an intestinal pathogen that causes severe diarrhea by producing potent toxins in the gut. C. difficile is a poor competitor and doesn’t usually cause trouble in people with a healthy microbiome, which keeps the pathogen at bay. But if you kill off a large number of helpful gut bacteria in the course of treating some other infection, C. diff suddenly has the house to itself. It flourishes dangerously and is incredibly difficult to dislodge.

If researchers can figure out which microbes are promoting or preventing specific conditions – obesity, diabetes, asthma – there is a chance they can grow tailored probiotics that we could take as treatments. This might even work for certain types of mental illness.

In the meantime, Jessica Finlay says there are still four things we can do. The first is to eat well. We can search out prebiotics, the high‑fibre and/or starchy foods that are most effective at nourishing the microbes in our gut. These include foods such as asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes, bananas, oatmeal, honey, maple syrup, legumes and (brace yourself) red wine! (The latter, of course, is to be consumed in moderation, but still!) There’s also much to be gained by eating probiotics, foods with beneficial live bacteria and yeasts: think kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, tempeh, yogurt and kombucha. You can also take probiotics in pill form, but keep in mind that they are not regulated by Health Canada or by the US Food and Drug Administration, so you should, at the very least, be skeptical about any enthusiastic claims for their effectiveness (see probioticchart.ca for a list of medically proven probiotics).

The second recommendation is to exercise, which is good for you anyway, but also appears to be good for your microbiome. And the same can be said for the third recommendation, which is to reduce stress. From a microbiome perspective, it seems that this is a condition that can be self‑reinforcing: if you are stressed, your microbiome adjusts and, according to mouse models, can perpetuate the tendency to be stressed. Anything you can do to avoid starting the spiral will help.

Finally, eat dirt!

Actually, neither Jessica nor Brett recommended that for adults. The real advice was to “get out there.” Open the windows or, better still, go outside. Spend lots of time with other people: shake hands, give them a hug, kiss your kids. Dig in the garden, pet the dog. And be cautious about using antimicrobial handwashes or, indeed, antimicrobial anything. Jessica complained that she bought a t‑shirt for running and found it was “antimicrobial.” She took it back. Most of the time, she says, the best cleaning tools are soap and water. (At the end of the day, we also might be shrinking away from the wrong things. The Finlays’ book advises that there are 10 times as many microbes on your cell phone as on your toilet seat. One of those clearly needs an extra wipe once in a while.)

Although the Finlays didn’t say so, a fifth recommendation might be to look for fun things to do and interesting people to do them with. Father and daughter were both effusive about working together on this shared project, with Jessica saying that, although Brett has always been “just Dad,” it was still “very validating that he wanted to work together.”

And the ebullient Brett seemed to sum up both the experience of writing and the promise of all this research, saying:

“Money doesn’t buy happiness; science does.”