A Last Love Letter to the Serengeti

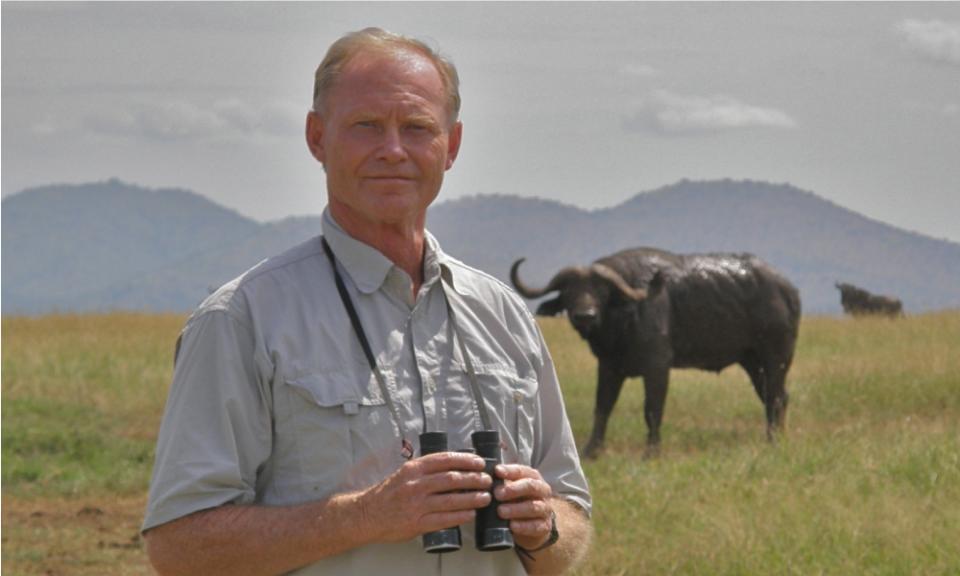

A zoologist explains his love of the Serengeti, and why it’s important for scientists to reach out to the public.

We were standing on a mound in the middle of the vast Serengeti plains – my wife Anne and I holding hands as we gazed to the west into the setting sun. This was to be our farewell to the Serengeti after 50 years of biological research in the most spectacular wildlife area in the world.

We were being filmed by a crew of four capturing the scene from behind us. Suddenly, 50 metres away, up popped the heads of two male lions, staring at us. We stared back until we noticed that there was dead silence behind us. Turning around, we saw the crew now back in their trucks straining their necks like ground squirrels in their holes, wondering what was about to happen. The lions, of course, weren’t interested in us. They were using the hillock just as we were – to get a good view. We enticed the ground squirrels back out of their holes to finish filming.

“All is not lost if we do the right thing.”

What better way to do this than through film? The Serengeti Rules tells the story of how researchers elucidated the rules that create ecosystems and keep them together. These are the organizing principles that determine what species can live in an ecosystem without going extinct.

I was born in Africa and was familiar with the countryside and habitats. But when I saw the Serengeti for the first time at the age of 21, I realized it was unique in the number of species it hosts and the spectacular migrations they performed. Why was the Serengeti different from any other place on Earth? What kept it that way? There had to be some higher order rules that allowed the Serengeti to exist – some framework to explain it. And these rules should also explain all other ecosystems in the world.

The Serengeti Rules starts by documenting my long‑term study, along with that of four other researchers, showing how mankind has damaged our environment, causing ecosystems to unravel and sometimes collapse completely. It illustrates these changes in the Amazon (environmental scientist John Terborgh), marine systems with killer whales (ecologist Jim Estes), the rocky shores with starfish (ecologist Bob Paine), and river habitats (zoologist Mary Power). In all these cases, the film shows how the rules of ecosystems have been abused by humans.

Then comes the Serengeti. This system had already collapsed by the 19th century due to an introduced disease called rinderpest. It killed off most of the migrating animals – indeed most of the wild animals of Africa. It was a catastrophe. My research recorded how the system was able to repair itself, taking a century to do so. Humans are still damaging our ecosystems, and this damage will disadvantage our grandchildren. But if we protect our ecosystems, use them carefully and even return lost species, we can, as in the Serengeti, repair them and keep them healthy. All is not lost if we do the right thing.

Nicolas Brown, the director of the film, was most interested in how five scientists got started and what drove us to ask our scientific questions at such an early age. To show us in the 1960s, he used actors to represent our early work. In my case, he also had the advantage of existing footage of me in the Serengeti taken by David Attenborough in 1967 and again in 1972, which was spliced into the film. We filmed the modern scenes in 2016, out on the plains and in the woodlands.

The first and most important rule was that all ecosystems have a self‑governing mechanism so that populations can’t get out of control – regulation. If humans overrule this mechanism, there are consequences such as outbreaks of insects and extinction. There are eight rules in all and it took me 50 years to discover all of them. But the research isn’t finished. There is much further to go. I’ve handed over this work to younger colleagues.These scenes describe how I elucidated the rules one by one, each taking, by chance, about a decade to finally unveil.

The message that ecosystems can be repaired needs to resonate with the public and we can share this message through documentaries such as The Serengeti Rules. The film shows the damage humans can cause but also how the right decisions can lead us to live in balance. Hopefully, it makes others ask themselves questions about stewardship of our environment, just as I did many decades ago.

Tony Sinclair is a Professor Emeritus of Zoology at UBC. The Serengeti Rules has been shown around the world at film festivals, earning numerous awards. It will be streaming on Netflix in the near future.

Website: theserengetirules.com