Fighting Fire with Fire

Having recently lived through the worst wildfire season on record in BC, Kelsey Copes-Gerbitz is the first to acknowledge that promoting the benefits of fire in the province’s interior forests is a hard sell. BC foresters have worked diligently – and often successfully – in the last century to supress fire, to prevent its outbreak or discourage its spread. And after seeing firsthand the threat and devastation of wildfires raging near her research area outside Williams Lake last summer, this UBC PhD student now has a visceral sense of why you might want to avoid fire at all costs.

But looking back into the scientific record, and plumbing more deeply into human memory – especially through her collaboration with the Williams Lake Indian Band (T’exelc) – Copes‑Gerbitz says two conclusions are inescapable: first, wildfire has always been an integral part of the BC interior forest ecology, and second, humans have often worked with fire more successfully than they have fought against it.

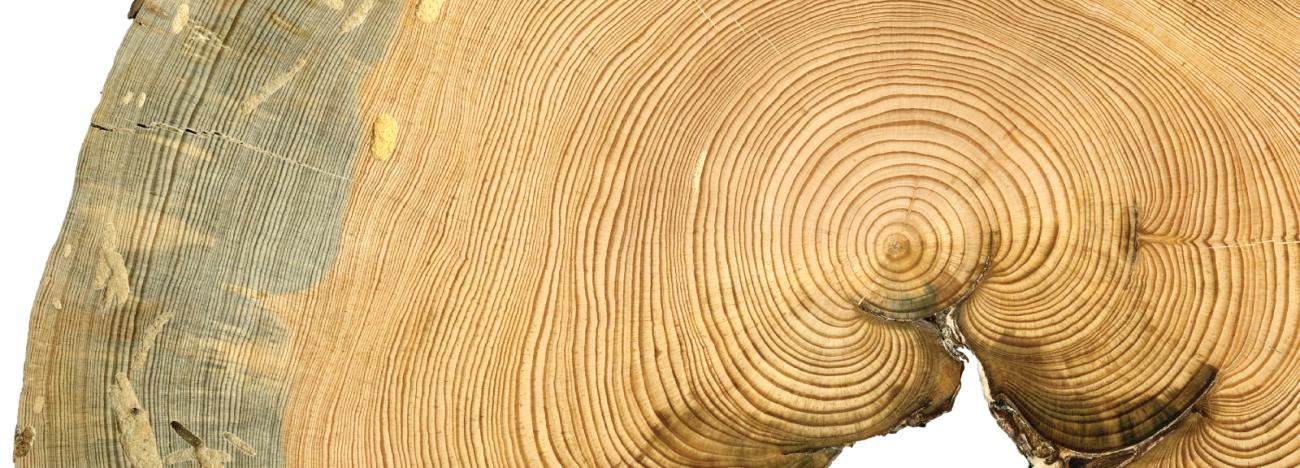

Copes-Gerbitz has just wrapped up the second year of what she anticipates as four years of interdisciplinary doctoral research in the UBC Faculty of Forestry. On the ecological side, she is looking at tree‑ring studies to establish a long-term wildfire record in the Williams Lake Community Forest, which is jointly managed by the T’exelc and the City. At the same time, she is working closely with community members, particularly with the T’exelc Elders, to better understand how humans have coexisted with fire over the centuries.

As previous research shows, “these areas used to have a lot of low severity fires – every five to 15 years,” Copes-Gerbitz says. But the outbreaks were patchy, “never hectares and hectares of devastated landscape as we saw last summer.”

Three things have changed. First, a century of increasingly effective fire suppression has allowed fuel to build up in the forests, so when fire breaks out, there is more to burn, creating blazes that are fiercer and run farther. Second, climate change has turned up the heat, or made the forest more fragile, for example by allowing the devastating spread of the mountain pine beetle.

The third factor – less well known, but closely related to the first – is that Indigenous people are no longer managing the forests with fire. It turns out that before colonial times, it was common for people to set lots of small, strategic fires, for purposes ranging from reinvigorating berry crops to managing game – for example, by attracting caribou that find better forage in forested areas where a small fire has reduced the dense undergrowth.

This doesn’t mean that anyone is planning to head into the woods with an underdeveloped plan and a package of matches, but it strongly suggests that Copes‑Gerbitz is the right person, at the right time and, perhaps surprisingly, in exactly the right place.

Before colonial times, it was common for people to set lots of small, strategic fires, for purposes ranging from reinvigorating berry crops to managing game.

The surprise arises because Copes-Gerbitz is, as they say, not from around here. She grew up in Hawaii, hiking the mountainside forests on the Hilo side of the Big Island. After high school, she moved to the mainland, choosing Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, because it offered her the opportunity to pursue a double major in environmental science and archaeology, reflecting a split interest in both landscapes and people.

After her undergraduate studies, Copes-Gerbitz began working with an ecological non-profit on forest management and restoration. There, she started to understand how difficult it is to manage the landscape in what she calls “a multi-value setting,” where you have to balance or accommodate ecological goals, economic goals and social goals all at the same time. She went on to do a master’s in environmental modelling at the University of Manchester in the UK, and, working afterward as an environmental consultant, she again found herself “the middle man between people with fundamentally different values – between people who want to develop and people who want to protect.”

The more she felt this tension, the happier Copes-Gerbitz became about the interdisciplinary nature of her studies to date. In a single discipline – or in a forestry faculty less interdisciplinary than UBC’s – Copes‑Gerbitz says you can wind up with scientists and ecologists who are inclined to shy away from people – who are accomplished in their area of expertise, but not trained in social science research methods.

But, Copes-Gerbitz says, “unless you can talk to people of all different perspectives – unless you can work collaboratively with everyone – change is going to be much more difficult to come by.” That’s why she chose to pursue her PhD at UBC, where her thesis supervisor is Dr. Lori Daniels, an expert in fire ecology who has worked hard to engage with communities throughout the province. In addition, Copes-Gerbitz benefits from the guidance of a social science methods expert, Dr. Shannon Hagerman, who has extensive experience working across the sciences in a policy context.

She started to understand how difficult it is to manage the landscape in what she calls “a multi-value setting,” where you have to balance or accommodate ecological goals, economic goals and social goals all at the same time.

And the move to BC has proved an excellent choice. “I’ve been loving every step,” Copes-Gerbitz says. “I’m loving the urgency of doing this kind of work.” To support it, Copes-Gerbitz applied for UBC’s Public Scholar Initiative award, which benefits doctoral students whose research is explicitly linked to purposeful social contribution and innovative forms of scholarship. She also landed a student grant from the faculty’s Aboriginal Community Research Seed Fund. Without these sources of funding, says Copes-Gerbitz, the long-term community engagement necessitated by collaborative work, and the ability to give back to the community, would have been difficult to fully realize.

Copes-Gerbitz says she is less concerned about finding “a job” after achieving her degree than she is about maintaining the impact of the work she is doing already. This is not one of those projects where you can usefully drop in, conduct your research and leave with the product, she says. Even if she succeeds in developing holistic and appropriate management strategies for minimizing the threat of catastrophic wildfire, the crucial final piece will involve engaging the community, building management capacity and, most of all, building public trust.

“Ultimately,” she says, “it’s a resilience approach. We are trying to build the capacity to be ready for what we don’t know is coming.”