Lay of the Land

“Because I was doing it at such a young age,” he says, “she taught me that I could learn something that seems impossible at first glance.”

At some point, however, he must have decided that the violin wasn’t going to pay the rent, so he looked to other activities. One day, shortly before his twelfth birthday, he saw a man in downtown Victoria riding a unicycle, playing a violin. “That’s for me,” he thought, and asked for one for his birthday. And so it was that one of the world’s foremost unicycle athletes was born.

“Unicycling is a rare sport,” he says, “because initially it’s so difficult to do. Most sports, even the ones that are hard to do well, are easy to do badly. Anyone can get up on a skateboard, for example, and teeter precariously down the street. But even an athletic person can barely go a metre on a unicycle to start, and that stops a lot of people from trying.”

Unicycles have played a very small part in the history of wheeled vehicles, and when he began riding they were novelty items aimed at children, circus clowns and jugglers.

Off‑road unicycling was a natural for Holm, who was, by the 1980s, a committed rock climber. He started riding trails around western North America, incorporating it into his rock climbing passion. But unicycles have played a very small part in the history of wheeled vehicles, and when he began riding they were novelty items aimed at children, circus clowns and jugglers. As he advanced in the sport, he bought off‑the‑shelf unicycles and customized them with bigger tires and reinforced frames, but they weren’t up to the rigours he put them through. Then, in 1998, he worked with a local machinist to build his own mountain unicycle.

By the mid ’90s, mountain biking was becoming a big thing on Vancouver’s North Shore and trails were being designed to challenge emerging mountain bike technology. At the same time, advancing video technology made it possible for riders and sponsors to film their escapades cheaply and easily. Holm’s new unicycle (and his skill level) proved a great match for the demands of those world‑class trails, and in 1998 he earned his first sponsorship from Norco Bicycles. A year later he began selling a small number of his branded cycles (Kris Holm Unicycles) through the online retailer, Unicycle.com. In 2003 he moved production offshore for international distribution.

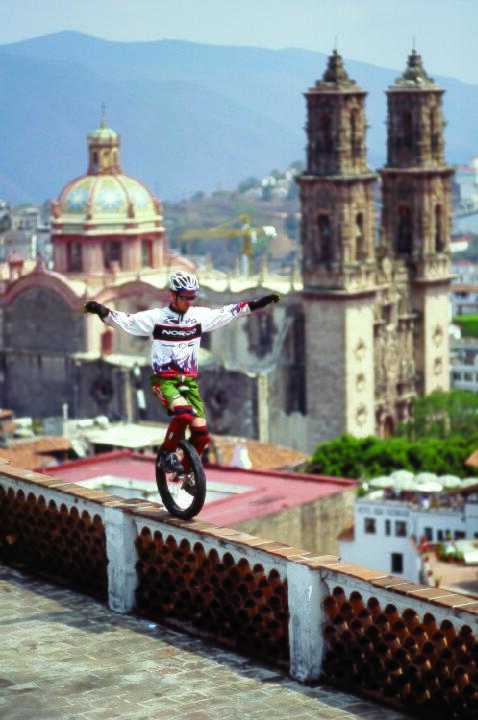

To promote the sport, he has been featured in more than 50 videos, wrote a book (The Essential Guide to Mountain and Trials Unicycling) and founded competitive unicycle trials – riding unicycles on obstacle courses – which has had its own world championship since 2002. He’s cycled up mountains in Central America, down a volcano in Bolivia and along the Great Wall of China, as well as up and down North Shore mountains.

As a business model, Kris Holm Unicycles is definitely a 21st century phenomenon. His unicycles are built and distributed around the world from factories in Taiwan. He developed a saddle that provides a comfortable ride over rough terrain, and his units come equipped with a state‑of‑the‑art disc brake. He also produces a line of protective gloves in Pakistan and a line of leg armour in China. All of this is conducted on the internet and without having to leave home except for an annual trip overseas to meet with suppliers. Kris Holm Unicycles are considered one of the top brands in the world. Each year, his company provides a grant to fund the most creative mountain unicycle adventure: The Evolution of Balance Award. As well, he sponsors his own Factory Team in international competitions, and was the first cycling company to join One Percent for the Planet, donating one per cent of his gross revenues to environmental causes.

Still, Holm considers his unicycle business and the sport itself to be his hobby. His intentional career, as he calls it, is in geoscience. He leads the geohazards group at BGC Engineering, which provides risk assessments of development and major industry projects for public and private clients. Holm and his colleagues assess debris potential in steep creeks that may flood; analyse slopes in danger of slumping; and investigate any other geological structure that may be subject to natural disruption. The team works with the Municipality of North Vancouver to assess potential damages from landslides and floods, stemming from the 30‑plus steep streams that careen through residential areas, and helps them determine strategies to reduce any impact. They also work in Canmore to help devise ways to prevent the kind of damage that occurred during the devastating 2013 Alberta floods. Holm has also worked in various South American countries and in northern BC to assess risks in mining and forestry sites.

“You learn to recreate geological history in this job,” he says, “to understand the forces that shaped a site over the past 10,000 years or more. You pose questions that have a direct bearing on people, where they’re living, what risks they face, and how safe they can be. It has a real impact on a community.”

Holm sees many parallels in his work as a geoscientist, as a unicylist and an entrepreneur. He’s been able to conflate his experiences and learning in seemingly disparate endeavours into a unified whole. For one thing, few people understand what he does as a professional geoscientist, hardly anyone else does it, and communicating the complexities of the activity is challenging. The same can be said about unicycling.

“There’s also a collective aspect to both types of work,” he says. “Even though there’s only one name on the brand, it can’t succeed without good social media managers, product builders and assemblers, distributors and retailers in different countries. Everything works better when everyone is inspired by a common interest. And that’s the same when I’m managing a geoscience project.”

But there’s another struggle, one that’s common to scientists and to elite athletes. “As a scientist, you have a passion for your discipline,” he says. “You’re good at it and you love it. Then, at some point you get a job and realize that you have to generate money, especially when you work as a consultant in a company. You’re balancing two extremes: the pursuit of excellence for its own sake, and the need to achieve good profits in business.

“It’s even more difficult as an athlete, especially in an independent sport like mountaineering or unicycling. Some people scorn you if you get sponsors because it seems that you’re selling out, you’re not pure. Suddenly I was on TV every two weeks. How do I stay true to the original reasons I ride? But I couldn’t do it at a world level without sponsorship support. What I learned in professional riding I’m able to translate into my professional consulting life: doing something you love just for the joy of it, but also doing it in such a way that you can make a difference and make money.”

“Risk is about management,” he says, “whether it’s in unicycling or professional work. It’s about focus, about engaging utterly in what you’re doing.”

Another parallel is the risk factor. By definition, investigating the potential of a damaging slope failure or rampaging creek and effectively communicating that to the client is fraught with professional peril. Similarly, racing down a mountain bike trail at breakneck speed (or cruising along the brow of the Chief near Squamish) is a heart‑pounding, injury‑inviting enterprise.

“Risk is about management,” he says, “whether it’s in unicycling or professional work. It’s about focus, about engaging utterly in what you’re doing. Anyway,” he adds with a laugh, “I’m able to focus better when I’m a little scared.”

Perhaps that’s why he didn’t pursue a career as a professional violinist. Not scary enough.

Kris Holm lives with his wife and two children at Wesbrook Village, UBC. Visit his website at www.krisholm.com.

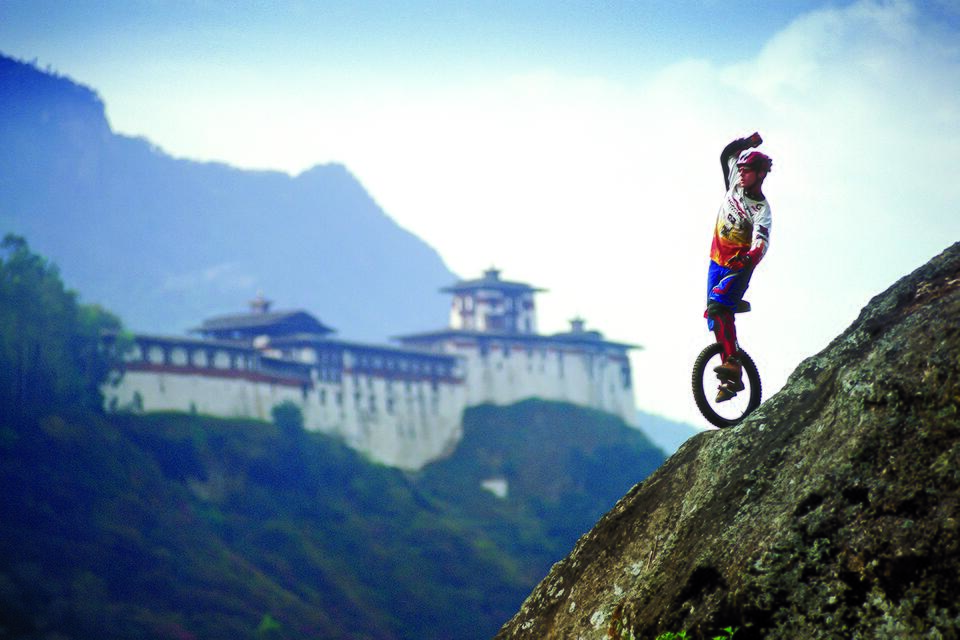

About the banner image

UBC alumni tend to be multi-talented, and Kris Holm – a professional geoscientist who also happens to be an accomplished unicycle athlete and entrepreneur – is no exception. It’s an understatement to say he likes off-road riding; here he is balancing in front of Trongsa Dzong, a fortress in Bhutan (Photo: Sean F. White).