Searching for Mexico’s Missing

All photos courtesy of Gobernanza Forense Ciudadana AC unless otherwise noted.

“If 43 students can go missing in a town in Guerrero, there’s no reason why 43 students from the university I teach at could not go missing tomorrow,” says Rodolfo Franco, a part‑time faculty member at Tec de Monterrey, as he gravely describes the human rights situation in Mexico. The country is on edge. It has been entrenched in a drug war for nearly a decade, and lately it’s become apparent that anyone could be a kidnapping target.

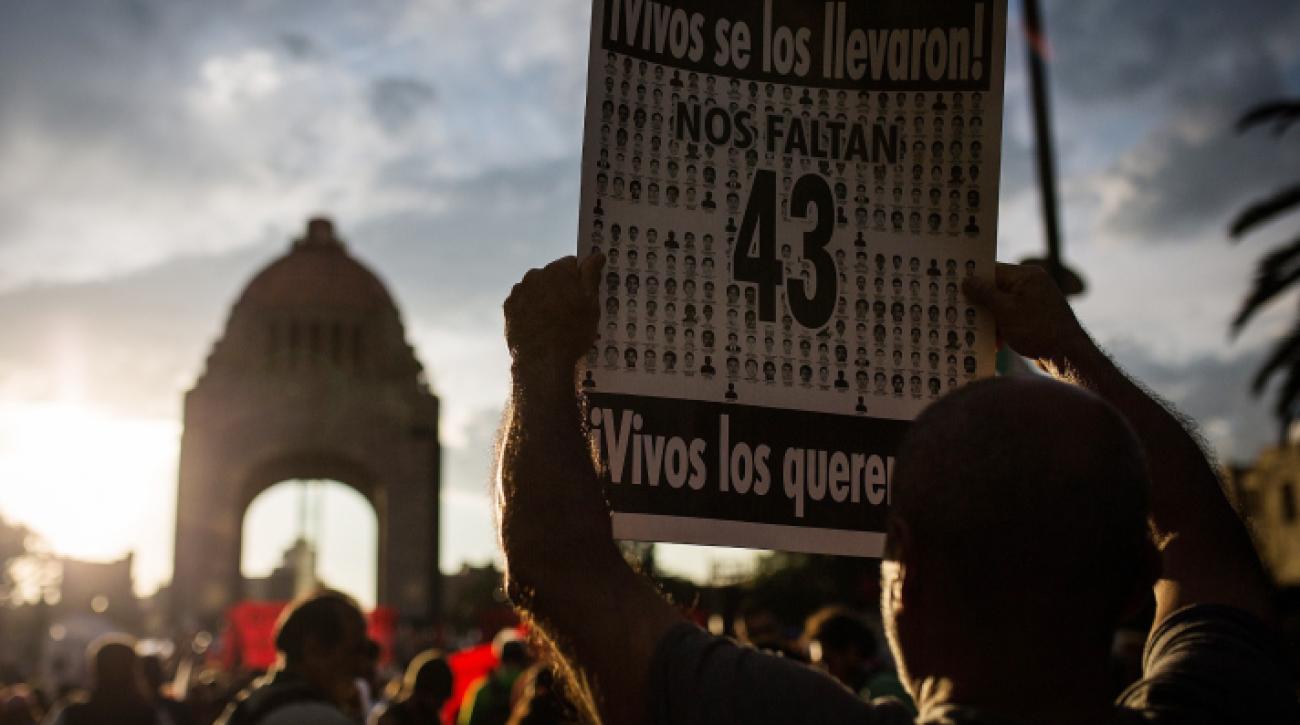

The 43 young men he’s referring to are the students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa who disappeared from the town of Iguala last September. The case made international headlines and led to massive street protests in Mexico City and across the country as citizens demanded answers. Although mass kidnappings are not uncommon in Mexico, this case was different for a couple reasons. First, these students were not involved with the area’s drug cartels. And second, from the beginning it was widely suspected that local authorities had played a major role in their disappearance. Although dozens of arrests have been made and at least one student’s charred remains have been identified, many questions still linger. There’s a pervasive feeling that the federal government only investigated the disappearances because the case was receiving so much international attention. The official version of events (that the students were likely killed after being handed over to a drug cartel by corrupt members of local law enforcement) is not fully accepted. The families of the missing men, along with large segments of the Mexican population, still believe the government is hiding something.

Their distrust is a result of deep flaws in Mexico’s justice system. Over the past decade, more than 27,000 people have gone missing across the country. While some are eventually unearthed in mass graves, official investigations are seldom thorough and most cases are never solved. Many families are left wondering what happened to their loved ones and unable to get closure.

Franco, who is the director of strategy and fund procurement for the recently formed Mexican NGO Gobernanza Forense Ciudadana (citizen‑led forensics), offers his perspective on why these cases are not often investigated. “At the local level it is a clear issue of corruption,” he says. “Police forces are certainly mixed with criminal organizations, and sometimes they’re at their service.”

While corruption explains why many individual cases are not investigated, the scale of the problem suggests a system‑wide failure at the federal level is also to blame. “I think it’s a matter of capacities and organization,” Franco says. He explains that the office of the attorney general regularly tells him that the government’s DNA database will soon have the capacity to distinguish between DNA samples from discovered remains and from the families of the missing, making comprehensive cross‑referencing and potential identification possible. Although this would be a step in the right direction, he finds it unbelievable that the database could have ever been designed without this function in mind.

“The government will never come to terms with the idea that this is a humanitarian crisis, and I think they’re very worried about their international reputation.”

Franco, whose graduate studies at UBC focused on human rights norms and the limitations of human rights systems, suspects the federal government has other reasons why it’s unwilling to investigate the thousands of missing persons cases that exist in the country. “I think the general perception is that this is regular crime,” he says. “The government will never come to terms with the idea that this is a humanitarian crisis, and I think they’re very worried about their international reputation.” Because of this, he explains, the government’s recent focus has been on crisis management instead of on building the institutions, rules and norms required to combat the underlying problems.

Regardless of the reasons, the families of missing people are not looking for excuses. They want answers. And in the absence of rigorous official investigations, citizens have begun investigating cases themselves. It was this reality that drove Franco and some friends from his undergraduate university to recognize the potential for a citizen‑driven approach to combatting the corruption, arbitrariness and lack of investigative transparency surrounding Mexico’s missing people. His friends founded Gobernanza Forense Ciudadana (GFC) in 2012 with this purpose in mind, to provide resources and a collaborative forum for families searching for loved ones.

Family members were learning about GPS technologies – contacting mobile phone companies to get data on the last known whereabouts of their loved one – and would often go to coffee shops and convenience stores to retrieve security tapes as part of their timeline reconstructions.

Franco explains that each state has its own definition of “disappearance” and its own forensic system. Because of this, jurisdictional issues can be a barrier to investigations. If someone disappears in Monterrey, for example, and their family lives in Mexico City, the authorities would open an investigation and begin their search in Mexico City. After a few enquiries, he says, they might discover that it’s impossible to gain access to remains in Monterrey, or that local authorities won’t cooperate. As a result, these investigations don’t lead anywhere. “There are families that watch the news every day to find out if a mass grave has been opened somewhere in the country, just so they can travel there and file a new complaint in that new jurisdiction,” Franco says.

In the face of these bureaucratic hurdles, and the fact that they rarely have access to remains themselves, families have been forced to pursue creative avenues in their investigations. When Franco’s friends conducted their feasibility study and started contacting families of missing people to see what they had been able to accomplish on their own, they were surprised. “We realized that they had been very thorough with their investigations,” he says. Family members were learning about GPS technologies – contacting mobile phone companies to get data on the last known whereabouts of their loved one – and would often go to coffee shops and convenience stores to retrieve security tapes as part of their timeline reconstructions.

“We realized there was a lot of knowledge among citizens,” he says, “but there were some problems.” First of all, the authorities seemed reluctant to listen to or act upon the information gathered by families. Second, the families were disorganized and not exchanging information. It was clear they needed a way to work together and leverage their collective forensic knowledge to pressure the government to act.

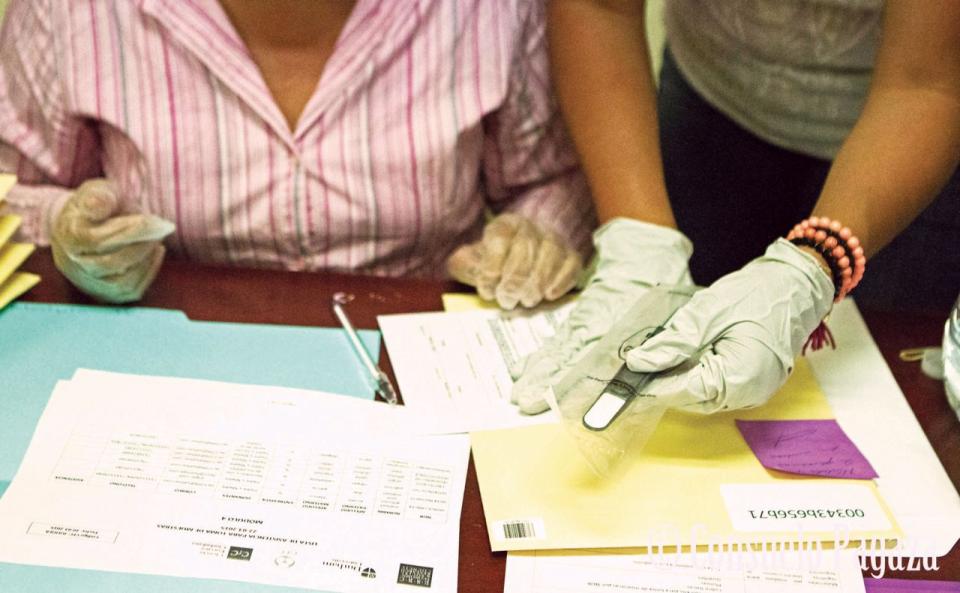

Recognizing this, GFC created an online National Citizen Registry of Disappeared Persons in order to start identifying families of missing people. They then got to work developing their idea for a citizen‑controlled DNA Biobank using mail‑in DNA sample kits, like those that are used for paternity tests. Franco explains that the team wanted to build the Biobank using basic, accessible technologies in order to demonstrate to the government how simple the task should be, given proper organization. “These Biobanks should be used to make massive cross‑references of non‑identified bodies and families that are searching for their relatives,” he says. “Once the Biobank is built and there is a critical mass of samples in it, we’d be able to argue due diligence and the government would be obligated to use the Biobank as a tool of investigation.”

Although building the Biobank is GFC’s main objective, the organization also holds workshops with the families of missing persons to educate them about forensic DNA so they are more effective at holding government officials accountable. GFC often hears from families who have contested the government’s DNA results and requested DNA reports, but received no response. Then, after filing petitions for more information, they discover no proof in the investigation file to suggest their DNA samples had been taken in the first place. “The way we see it,” Franco says, “the Mexican government will only be able to present legitimate and credible results insofar as they open up the forensic processes and explain how they get the results they get.” He says that for this to happen, civil society organizations need to monitor the government and pressure them to change their processes.

Franco says that Guerrero’s government is beginning to understand that citizens are demanding more accountability and have little tolerance for superficial investigations that are only conducted for appearances’ sake.

Franco is starting to see small signs of progress in this regard. He talks proudly of a GFC member in the state of Guerrero who recently stood up in a public forum and questioned the government’s DNA sampling practices based on knowledge she learned at a GFC workshop. “She was able to tell these people that they were sampling the wrong family members, because [this particular case, which involved identifying an older individual, required] a special mix of DNA samples, and not necessarily the ones they were taking.” He says that Guerrero’s government is beginning to understand that citizens are demanding more accountability and have little tolerance for superficial investigations that are only conducted for appearances’ sake.

It’s a small step, and there’s still a lot of work to be done. GFC has funding to collect 1,500 samples and aims to have the Biobank populated with complete DNA profiles for at least 500 missing person cases by the end of this year; an organized group of citizens will have accomplished a task that the government, with all of its resources and expertise, has not.

Although Franco hasn’t had anyone close to him disappear, he knows he is not immune and feels a moral obligation to continue the work. He is also driven by compassion. Late last year in Monterrey, with the help of a Peruvian team of forensic anthropologists, GFC performed the first independent citizen‑led exhumation. For a number of reasons, the family of missing woman Brenda Damaris Gonzalez Solis had serious doubts about the identity of the remains that the government had given them. Following the exhumation, GFC was able to conduct DNA tests that definitively proved the remains were those of their daughter. Although the news was heartbreaking, this family could finally reach some sense of closure. “It’s not all about finding what the government does wrong,” Franco says. “It’s also about providing families with a scientific basis to mourn.”

Expert Insight: Mexico’s missing students

By Glenn Drexhage

Near the end of September 2014, 43 students went missing in the Mexican town of Iguala. Reports indicated that the students were murdered, their bodies burned – another tragic turn of events in a country that has endured horrific violence and state corruption. In December, Agustin Goenaga, a Mexican doctoral candidate in UBC’s Department of Political Science, discussed the disappearance, examined its implications for Mexican democracy and highlighted a Canadian angle.

Violence has plagued Mexico in recent years, yet the disappearance of the 43 students has produced a particularly strong reaction. Why?

These developments challenge the narrative that victims of violence are involved in illegal activities. If innocent civilians are targeted, they’re viewed as collateral damage.

What’s different now is that the 43 students had absolutely no ties with organized crime. This is something that even the attorney general has publicly stated.

Second, the first actors involved in this crime were local police forces, following orders of Iguala’s mayor. They were the ones who opened fire against students, arrested them, detained them and allegedly handed them over to members of a criminal organization to torture and execute.

How have the government and opposition parties responded?

The president has started a new nationwide strategy to combat organized crime, and deal with conflicts of interest and corruption amongst public officials.

The brunt of the new program is an initiative to dismantle municipal police forces, and create 32 forces at the state level, as an attempt to fight the corruption of local police officers.

In many municipalities, local police forces are indeed the most vulnerable to corruption. But dismantling them also removes actors who historically served as mediators in illegal activities, managing the violent escalation of small conflicts in this ad hoc way.

There is also an assumption that corruption does not touch the state or federal levels. This is false. Former state governors, national union leaders and federal secretaries of state face accusations of corruption. Even President Peña Nieto is trapped in a conflict-of-interest scandal.

What are the implications for Mexican democracy?

Civil society has mobilized in ways unseen until now. We’ve had demonstrations in the streets all over Mexico and around the world.

These events are serving as a trigger for civil society to push the political parties to be more responsive. Maybe there is also the potential for a new coalition of political forces to emerge.

A recent Vancouver protest highlighted concerns about Canada placing Mexico on a so-called “safe list.” Can you expand?

Immigration Canada put that decision in place in February 2013. This was based on the idea that it has limited resources to deal with claims for asylum and refugee status. The implications are that Mexicans potentially asking for asylum will face higher obstacles to achieve that.

The justification for placing Mexico on the “safe list” comes from the way the Mexican administrations have presented themselves to the international community: as defenders of human rights that are trying to implement and enforce the rule of law – and in the process are facing an escalation of violence.

But the recent events put this image of the Mexican state in question. The state has not proven itself capable of defending human rights, protecting vulnerable populations or prosecuting violations. In the students’ case, the state was actually the perpetrator of those crimes.