The University Opens, At Last

UBC commenced operations in the midst of an economic slump and the First World War.

All photos courtesy UBC Archives.

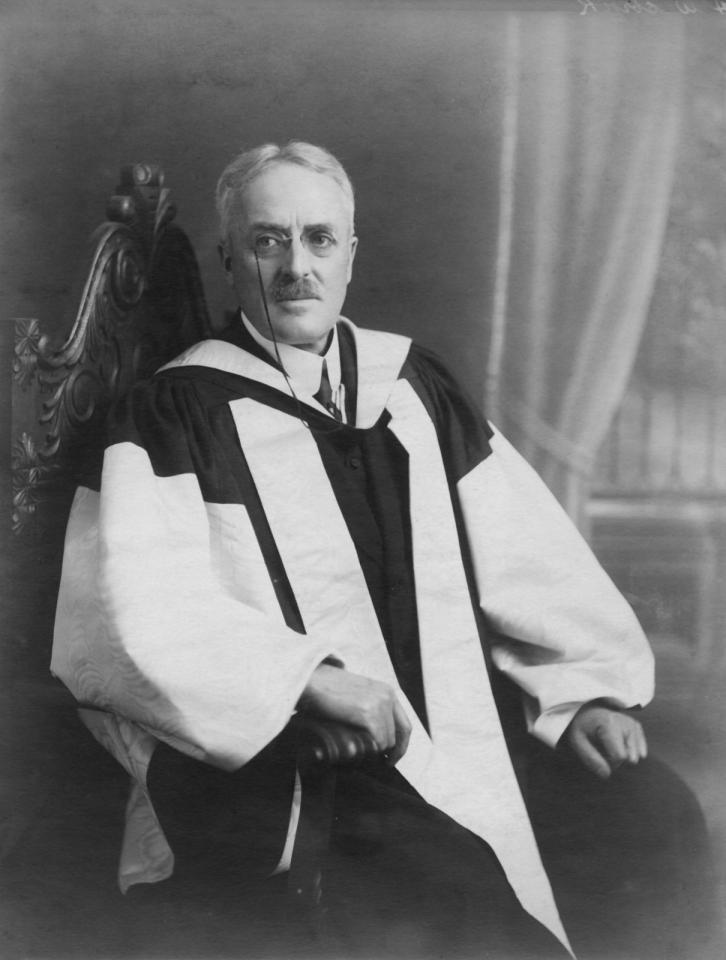

When he first arrived in Vancouver in 1913 to assume the presidency of the University of British Columbia, Frank Fairchild Wesbrook was promised that the provincial government would spare practically no expense to establish the university and ensure that its facilities and academic programs were comparable to other Canadian universities. He was told at a meeting with Premier Sir Richa[audio mp3="http://trekmagazine.alumni.ubc.ca/files/2015/10/hailubc.mp3"][/audio]rd McBride on May 30 that UBC would receive $2.8 million over its first two years, plus an additional “ten million if need be... [and] whatever [additional] sums were necessary from time to time.”

The campus designs proposed by the firm of Sharp & Thompson, chosen as university architects that same year, promised facilities as impressive as any in North America. The first buildings at Point Grey, which had been selected as the location of the campus in 1910, were due to be completed in time for the start of classes in 1915. Wesbrook’s dream of a “Cambridge on the Pacific” – for which he had given up his position as Dean of Medicine at the University of Minnesota – looked well within reach.

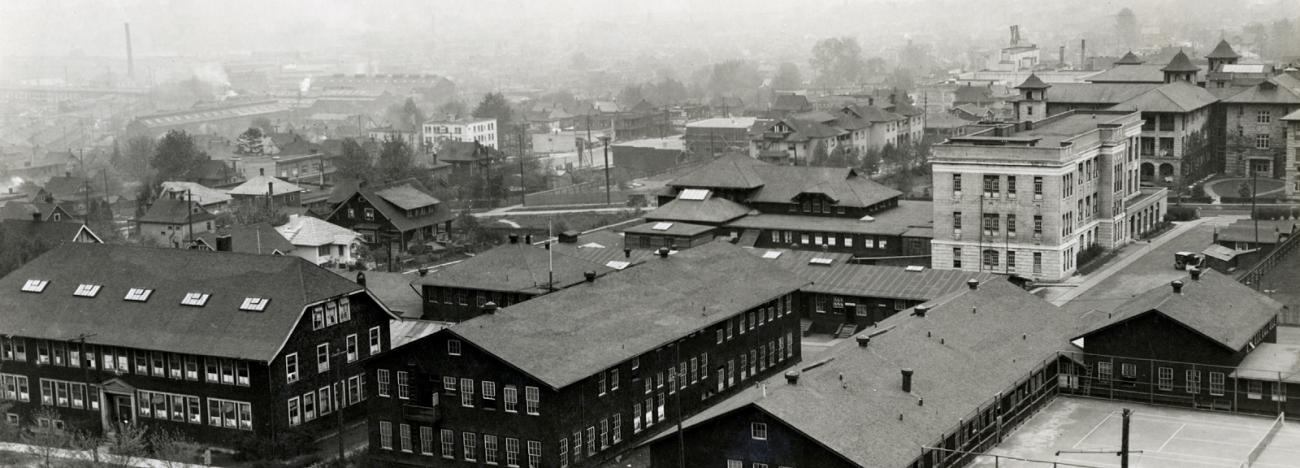

Two years later, the dream had given way to a harsh reality. An economic slump starting in 1913 and the beginning of the First World War the following year had combined to divert money, resources, and political will away from the university project. In January 1915 the initial budget was set at only $175,000. Proposed courses of study were cancelled or postponed indefinitely. The Point Grey campus would not be finished, although land‑clearing and construction of the Science Building had begun. It was still expected that UBC would open its doors to students in September 1915 – but where?

Since 1908, McGill University College of British Columbia had provided post‑secondary education for the province. It was based in the Fairview neighbourhood of Vancouver, in two buildings erected three years earlier at 10th Avenue and Laurel Street, adjacent to Vancouver General Hospital. Only the first two years of arts and science instruction were offered; students wishing to complete their degrees had to go to McGill University in Montreal, or some other institution.

Premier McBride’s government insisted that UBC would have to begin operations in the buildings of McGill BC, which would cease operations upon the inauguration of the university. The president and Board of Governors protested strenuously, insisting that at the very least temporary facilities should be erected at Point Grey for 1915, with operations moving into the Science Building upon its completion. But the government was adamant. Only current work on the concrete skeleton of the Science Building would be funded to completion. UBC would have to make‑do with the McGill BC facilities and whatever additional temporary structures could be erected at the Fairview site.

There is only one thing necessary now to make the University of British Columbia blossom into a full‑fledged university with perfect credentials, and that is a ’varsity “yell”.

– Vancouver Daily World (30 September 1915)

With the circumstances of the university’s immediate future out of their hands, Wesbrook and his staff proceeded with planning for its inauguration as best they could. Faculty were recruited from other institutions, sometimes after being interviewed by Wesbrook himself. In addition, many of the academic and administrative staff from McGill BC were retained by UBC. Altogether, for its first year of operation UBC would have a teaching staff of 34 – of whom two, classics professor Harry T. Logan and dean of Applied Science Reginald W. Brock, were on leave for overseas military service – and 12 administrative staff.

Registration for classes was scheduled to begin on September 27. McGill BC students were allowed to continue their courses of study at the new university, with those who had already completed their third year of study coming back for the fourth year and expected to finish as UBC’s first graduates in 1916. At the same time, more than half the projected student body would consist of first‑years. Most new universities begin with a freshman class and perhaps a handful of older students. By contrast, UBC would boast a full complement of undergraduates from all years, in the faculties of Arts and Applied Science:

| Men | Women | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arts: | 4th year | 21 | 17 | 38 |

| 3rd year | 25 | 20 | 45 | |

| 2nd year | 40 | 33 | 73 | |

| 1st year | 81 | 81 | 162 | |

| Applied Science: | 3rd year | 9 | – | 9 |

| 2nd year | 19 | – | 19 | |

| 3rd year | 33 | – | 33 | |

| Total | 228 | 151 | 379 |

The third faculty, Agriculture, existed on paper only. Although Dean Leonard Klinck would offer an introductory course in agriculture that year, a full program of agriculture classes would not be offered until 1917.

In addition to those listed above, 56 McGill BC students who had enlisted – many of whom were already serving in the front lines in France – had declared that they would continue their studies at UBC at the end of their military service. Wesbrook and his colleagues decided that, as their college had ceased to exist, these soldier‑students were without an “alma mater,” and so should be included in the UBC student body – in addition, any fees they might owe would be waived. With these overseas men included, the student body for 1915/16 would eventually total 435.

Students and staff would launch their academic careers in facilities that were a far cry from what Wesbrook had originally been promised. McGill BC had left its two buildings in Fairview to its successor: a two‑and‑a‑half storey wood‑frame building at the southeast corner of 10th Avenue and Laurel Street, and a single‑storey structure, also of wood construction, immediately beside it. These would become known as the Physics and Chemistry buildings, respectively. Also included among the college’s assets left to UBC were its library collection of 1,910 volumes, and assorted laboratory and office furniture and equipment.

In addition, the Vancouver School Board agreed to loan the chairs and desks that had previously been used by McGill BC. The board also granted university students access to laboratory and workshop facilities at nearby King Edward High School.

Perhaps most importantly, Vancouver General Hospital was very generous in allowing the university to expand its presence across its property. VGH board chairman J. J. Banfield agreed to the construction of two additional “temporary” buildings, each single‑storey and of wood‑frame‑and‑shingle construction, on Laurel. Completed that summer, these would house classes and laboratories for geology and mining.

Finally, the provincial government had paid for the construction of a new, permanent building for VGH’s use as a tuberculosis control and treatment centre, on the condition that it be loaned to the university for as long as it was based at the Fairview campus. For UBC it would serve as space for the university administration, the Library, and the Faculty of Arts – the latter gave it its unofficial name of the Arts Building.

By September the Library collections had grown to 30,000 volumes. The Library itself was located on the first floor of the east wing of the Arts Building. A small reading room, with seating for about 35 students, was established in space originally intended as a south‑facing deck for hospital patients. The bookstacks were located in a larger room next door.

The Library collection was not yet fully catalogued – the books were simply grouped on the shelves according to general subject area. Acting librarian John Ridington had been hired on a temporary basis in August 1914 only to unpack and catalogue books. He was officially appointed in December 1914, “in charge of cataloguing Library,” although he had no formal training as a librarian.

August and September of 1915 presented a picture of controlled chaos in and around Fairview. The university’s offices were still downtown; the new space in the Arts Building had to be made ready. Office walls and partitions were put up, and telephone lines installed. Wesbrook’s attention to detail was such that the itemized costs of each project were noted in his diary. His diary was full of to‑do lists, appointment reminders, and notes to see so‑and‑so re. such‑and‑such. A reminder of his wife’s birthday on August 7 was written in red ink.

The finalized text for the first UBC calendar was sent to the King’s Printer on August 2. When it was published the following month, Wesbrook made sure complimentary copies were sent to government officials, local dignitaries, and other university supporters. Demand for this first tangible product of the university became so great among the general public that copies of the calendar disappeared as quickly as they were produced.

The move of the university’s offices from Hastings Street to Fairview happened on September 13. President Wesbrook wasn’t even in town that day – the minister of education had delegated him to speak to a meeting of school trustees in Chilliwack. His first day at work in his new office was September 16. As he wrote in a letter a few days later: “We have left the Hastings Street offices and moved in on the workmen which hurried them and inconvenienced us but I think on the whole the results will be satisfactory.”

Even in the middle of such a period of unremitting activity, Wesbrook still had social obligations to fulfill. Perhaps the most important of these came on September 18 when he and his wife had the opportunity to meet Canada’s Governor General, His Royal Highness the Duke of Connaught. The Duke was very interested in military affairs and Canada’s role in the war. Wesbrook took the opportunity to tell him about UBC’s plans for an officers’ training corps.

Other visitors to Vancouver had to be met and shown around. Local friends, colleagues, and dignitaries were invited for dinner. As new university staff arrived to assume their posts, Wesbrook would often meet them in person.

The university’s actual opening was to be a quiet and understated affair. No special ceremonies were planned for Thursday, September 30. Wesbrook’s diary entry for that day was brief: “9 a.m. – Students assembled meet classes in 4 groups with 1 Registrar & Mr. Klinck.”

Another milestone came on the afternoon of September 27 when Wesbrook presided over the first meeting of the faculty. The president declared that he did not want the university administration decentralized among the faculties and departments, and preferred a unitary system. He proposed an administrative body consisting of the deans and department heads. Details of management would be assumed by committees, the functions and membership of which Wesbrook had already carefully considered before the meeting. Wesbrook’s centralized system would persist until 1921, when administrative responsibilities were devolved to the academic units.

The university’s actual opening was to be a quiet and understated affair. No special ceremonies were planned for Thursday, September 30. Wesbrook’s diary entry for that day was brief: “9 a.m. – Students assembled meet classes in 4 groups with 1 Registrar & Mr. Klinck.”

One reason for the lack of fanfare was that there was no auditorium or other space large enough to hold the more than 300 students who were present that first day. Instead, they were organized into four groups in four classrooms. Each in turn was visited by the president and members of the university staff. To each group Wesbrook read a letter he had received from Premier McBride:

This being the week upon which University work in this Province begins, I take this opportunity of writing to you and expressing my pleasure at the fact that in educational matters we have reached another milestone of progress. I want to congratulate you upon having entered upon the actual duties for which you have for some time been so assiduously preparing, and to congratulate the people of British Columbia upon their at last possessing an institution that will some day rank with the great Universities of the Continent...

I want you, on my behalf, to extend greetings to your Colleagues and welcome the Students, many of whom will undoubtedly occupy positions of great responsibility in British Columbia, to fit them for which is one of the objects that gave the University being.

It was also felt that owing to wartime conditions and the general public anxiety regarding the war, then entering its second year, it would not be appropriate to hold any formal ceremony or celebration. Instead, Wesbrook looked to the future. Opening day was only the beginning for UBC – there would be opportunities ahead to celebrate the university’s accomplishments. As he wrote to Premier McBride later that day,

We shall hope that when next spring we are able to present candidates for the first degrees granted by the University of British Columbia, there will be opportunity for some formal demonstration, at which time the people of the Province may see something of the work undertaken and accomplished, and that on such an occasion, they may have some right to congratulate themselves upon their determination to establish a people’s university.

UBC’s relatively low profile on opening day did not mean that it escaped media attention. Newspapers from Vancouver to Victoria to Vernon all reported on the university’s launch. An editorial in the Vancouver News‑Advertiser noted its modest beginnings and the difficulties of launching such a major enterprise in wartime, but concluded that:

[President Wesbrook] is a resourceful and capable organizer and finds himself now at the head of a school which starts out much better equipped and manned, and with a far larger attendance, than the other universities of Western Canada. It is only just to say that the university would not have been in this position if it had not fallen heir to educational assets of McGill University College, which has laid a substantial foundation for the larger enterprise now undertaken by the provincial university.

A separate article in the News‑Advertiser concluded, “the enthusiasm of the faculty is dominated by their desire to see that the university fills its proper place in the intellectual and industrial progress of the province... Its great future can but dimly be divined.”

The Library collection was not yet fully catalogued – the books were simply grouped on the shelves according to general subject area.

That day’s feature article in the Vancouver World paints the most vivid surviving picture of UBC’s inauguration:

There is only one thing necessary now to make the University of British Columbia blossom into a full‑fledged university with perfect credentials, and that is a ’varsity “yell”.

... There were the fresh‑faced and somewhat unsophisticated freshman, the sophomore with his year of college tending to make him regard the “new man” with mixed feelings of kindliness and pity, the studious third‑year man and the fourth‑year student, eagerly waiting for the degree that shall be the “open sesame” to the great world of struggle and fame.

When the representative of The World crossed the threshold of the Arts building at 9 a.m. over 200 eager students were crowded together in the atrium waiting for the door to their respective class‑rooms to be thrown open. The buzz of conversation, such as is only heard on first days, droned through the vestibule. In one corner a group of girls were enthusiastically examining new text books. In another two fourth‑year men were debating the war and military training. Two Japanese students sat as motionless as statues on a long bench, while a group of young ladies and young men eagerly reviewed the names of the successful candidates at the recent supplemental examinations, published on the announcements’ board on the wall.

After the president addressed each of the assembled student groups, the professors gave general outlines of study for each of their courses, and advised students as to where to purchase textbooks and other essentials. The students were then dismissed. Classes would start in earnest the next day.

With that, the University of British Columbia was launched as the country’s newest post‑secondary institution. Its beginnings were far more modest than had been imagined just two years before. Thoughts of the war weighed heavily on students and faculty alike. At spring convocation – which President Wesbrook intended as UBC’s “real” coming‑out party – the graduation gowns would be trimmed with khaki thread to honour those students who had enlisted.

Nevertheless, optimism and enthusiasm pervaded the Fairview campus. Those feelings would be embodied by President Wesbrook when he wrote later to his friend, provincial forester H.R. MacMillan: “If we do not accomplish good work, it will not be because we do not have good timber. I am delighted with the students individually and think they will develop the University spirit although as yet they have not had a chance.” Wesbrook’s optimism for the future of UBC would be justified over the next century.

UBC got its first fight song, Hail UBC, in 1932, composed by Harold King, BEd’32, (file courtesy UBC Archives).