Saving the Farm (Round 1): John Young’s dairy

When John and Mary Young and their six children boarded a ship in Glasgow, Scotland, to move to UBC’s farm in August 1929, they couldn’t have known what they were getting into. With 24 cows (and one bull) in tow, John Young was charged with establishing and maintaining a dairy herd for the university’s Faculty of Agriculture. There were already Jersey cows at the site, but Young and his herd of cattle were employed to ramp up the faculty’s dairy cattle research program.

He could be forgiven for taking a flyer on the opportunity half a world away. As the tenant operator of his family farm, “Waterside Mains,” in Dumfriesshire county, he had nursed his herd through a severe bout of brucellosis and was faced with a crippling rise in the cost of his farm’s lease. When he was approached by a kindly gentleman from a university in the colonies, he saw the offer as something he couldn’t refuse.

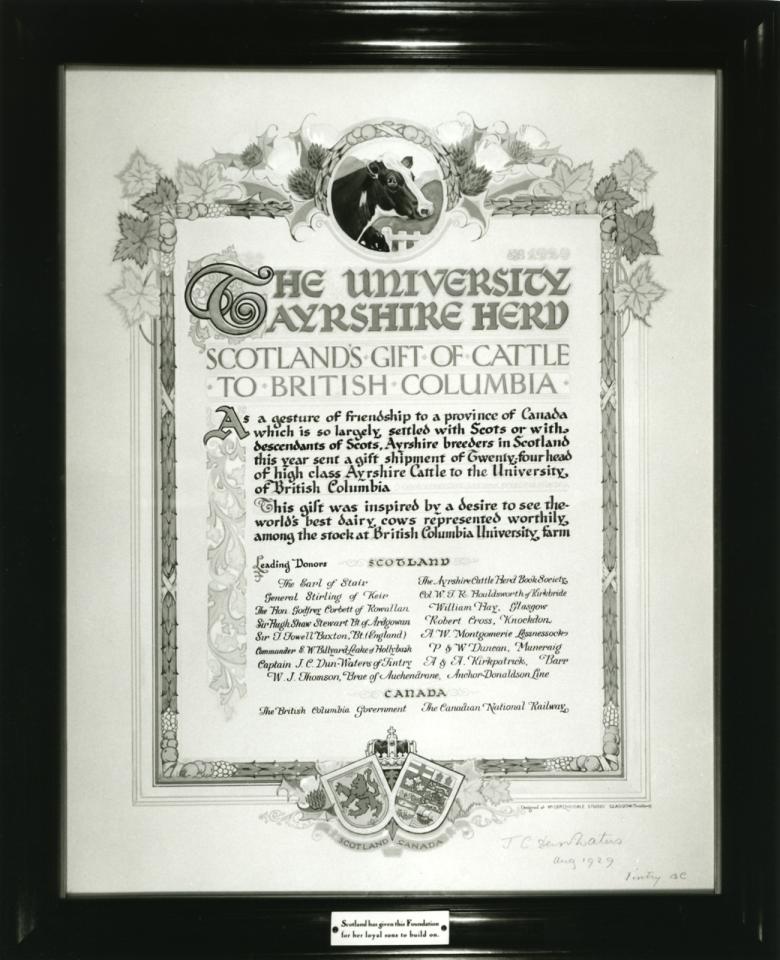

Young (and his cattle and family) were recruited by UBC professor H.M. King, who was dispatched to Scotland by the university to find a herd of Ayrshire cattle – along with their herdsman – to populate the dairy farm. A certain Captain J.C. Dun‑Waters, a fellow Scot and owner of the Glasgow Herald newspaper, operated a farm in Fintry, BC (across the lake from Kelowna). He was interested in helping develop a powerful Faculty of Agriculture at the fledgling university, and saw a healthy dairy farm as key to that success. In fact, one of the essential elements in selecting the Point Grey site in 1911 was its ability to support a teaching and research farm as the central focus of the university. Dun‑Waters was convinced that the Ayrshire was the only breed of cattle worth using at a teaching farm, and offered to help fund the purchase and transport of a herd to UBC.

Loaded onto floats and preceded by a pipe band, the elegant, long‑horned stock was paraded through the exhibition and Vancouver’s downtown before being hauled up to Point Grey and their new lives as “the best examples of the breed ever seen in this part of the world.”

In June 1929, Young et al set sail and arrived 10 sea‑sick days later in Quebec City. (His youngest son, Archie, now 87, remembers being the only member of the family who didn’t spend most of the trip in the latrine.) After six weeks of quarantine the cattle were put into railcars and trained to Vancouver where they arrived on August 10 in the middle of the Canadian Pacific Exhibition (now the PNE). Loaded onto floats and preceded by a pipe band, the elegant, long‑horned stock was paraded through the exhibition and Vancouver’s downtown before being hauled up to Point Grey and their new lives as “the best examples of the breed ever seen in this part of the world,” according to a newspaper report.

But the UBC campus was still in its infancy. Sod had only recently been broken at the farm site – around the old “B” parking lot, which is now a residential district – and the new barn hadn’t been fully prepared for a large‑scale dairy operation. Vancouver was still a rugged frontier town with limited resources, and the downtown was a rough, hour‑long tram ride away. John, Mary and their six children had to live in a two bedroom apartment over a store at the edge of campus for the first two years. The gentle nuances of life on a farm just outside the town of Thornhill in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, must have seemed like a misty dream.

But the Youngs were hearty Scots, used to the vagaries of farming life, and took to their new world with determination and high energy. Mary Young took a job teaching kindergarten, English and piano in Japantown, and became a champion of Japanese rights during the internments of World War II.

John Young began the arduous process of building the farm from scratch while helping develop programs to teach Aggie students the art of raising dairy cattle. Using his years of animal husbandry experience, he began to breed a larger Ayrshire herd. His spectacular stock included three of the most famous Ayrshires in the country: “Rainton Rosalind V” had such amazing milk production that she required milking four times a day and won many provincial and national awards, including the Grand Champion Female in 1934 for the highest daily, monthly and yearly milk yields in Canada. “Ardgowan Gladness II” was consistently awarded for the high butterfat content of her milk and “Lochinch Lassie,” as well as being an excellent milker, was a first rate breeder. She bore the famous bull “Ubyssey White Cockade” that sired some of the later stock’s most successful milking cows. These three cows were university stars in the Thirties.

In those days, managing a herd involved more than milking, feeding and breeding. Young and his family grew and harvested crops of hay, dealt with disease and injury to the animals, raised pigs and grew vegetables. Fortunately, he was able to use agriculture students and employ a small staff to work on the farm, but John and his family did the bulk of the work. Son Archie has fond memories of bringing in the wheat, working with the horse team and preparing prize cows for exhibition shows. All the hard work seemed to be paying off. Young was even able, after two years, to move his family into a four‑bedroom house adjacent to the farm.

The Great Depression that started in 1929 began to have a serious impact on British Columbia by 1931. Provincial budgets were slashed, and money earmarked for the new university was severely curtailed. If not for a determined campaign by students and faculty, UBC itself would have been shuttered. As it was, budgets for the faculties were cut dramatically, and the farm, it was decided, would be closed down, employees let go and the stock sold. But John Young had a different idea. He worked a deal with the university where he and his family would run the farm as a commercial dairy, supplying products to residents in the University Endowment Lands area as a way of making the enterprise self‑supporting. The university agreed, though administrators were dubious, and the UBC Dairy was born.

These were the days before automation, antibiotics and wide‑spread pasteurization, which meant that long hours and hard work were the only pathways to success. John Jr. was required to quit school to help manage the dairy, and his brothers, Dave, Alastair and Archie, and sisters Grace and Isobel devoted themselves to the arduous tasks of daily hand‑milking and delivery. In later years, Jean and Andrew, two new “bairns” added in the early ’30s, also pitched in. Archie received special dispensation from a local constable to drive the milk truck in the neighbourhood though he was only 14. But a real hardship befell the Youngs when John Jr. died in 1935 of a ruptured appendix. He had been his father’s right‑hand man since the family left Scotland, and his loss was keenly felt by the whole family.

In spite of it all, the family kept its strength and focus and maintained an efficient, well‑run farm that supported the faculty’s mission to advance research into cattle management, dairy production and animal husbandry. The commercial aspect of the dairy, during these economically bleak days, was a rare bright spot in UBC operations. As well, Young’s acumen in business and animal husbandry turned the 24 cows and one bull into one of the finest Ayrshire herds in Canada.

As the Thirties wore on, the university’s finances eased enough to enable it to generate some funding for the farm, and Young was able to acquire new equipment, including a pasteurizer, which made the home delivery schedule a little less hectic. But the war began in the late 1930s, and sons Dave and Alastair enlisted in the Air Force. To the family’s great anguish, Alastair was shot down in March 1944. Dave returned to the farm after the war and attended UBC, earning a BA in Agriculture in 1947. Younger brother Archie graduated the same year in Science.

By 1951, after 22 years of heroic work and dedication, Young decided it was time to retire. With Dave working in Ottawa with the federal government, and two of his other children studying at UBC, there was no one to take over the farm. Dairyland, then becoming one of the dominant agri‑businesses in the province, took over the farm’s delivery business, and the farm itself eventually divested itself of its livestock. But John Young’s legacy – hard work, determination, a sense of constant improvement and advancement – was to establish a strong foundation for dairy cattle research at UBC and the development of the Dairy Education and Research Centre in 1996. His spirit has become a hallmark of the university and the prime inheritance of the Young family.

Thanks to John Young’s grandson, Don Young, BSc’89, MD’94, for his biography, For All Thy Kith ’n Kine, and to Archie Young, BA’47(Science), for his insights.

The John and Mary Young scholarship was established in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems (the former Faculty of Agriculture) to support a grad student interested in dairy cattle research. For more information on contributing to the scholarship’s endowment, please contact Niki Glenning at 604 822 8910 or niki.glenning@ubc.ca.

Saving the Farm (Round 2): The Farm Reinvented

A farm of some description has been a part of UBC’s Vancouver campus since the establishment of the university site on Point Grey. However, the farm’s size, location, purpose, and operations have all seen many changes over the years.

In the decades following the Second World War, the diminishing socioeconomic importance of agriculture in the province was mirrored in campus growth patterns, as new athletics fields, parking lots, and academic buildings displaced former farmland.

Eventually, the second‑growth forest on the far south of campus was cleared to make way for new agricultural facilities, but by the late 1990s, activity had declined significantly – some operations having moved to new locations in Agassiz, BC. By 1997 the farm had been earmarked as a “Future Housing Reserve” in UBC’s Official Community Plan.

In 1999, however, students enrolled in the new Agroecology and Global Resource Systems programs “re‑discovered” the south campus field areas. They envisioned the land as an integrated farm system, which would provide a practical, experiential complement to the sustainability theory being taught in the classroom. It was a vision that conflicted with the Official Community Plan, and it sparked a decade of discussion about the future uses of the land.

Meanwhile, after the publication in 2000 of a vision document entitled “Reinventing the UBC Farm,” faculty, staff, students, and community members worked together to bring previously fragmented field areas together into a single working farm and forest system that delivered a growing number of programs to students and researchers in many different disciplines.

Despite this, by the summer of 2008 there was great concern among the farm’s users and supporters that it would be replaced by market housing. A “Save the Farm” campaign mobilized significant support, culminating in a petition with 16,000 signatures and a Great Farm Trek on April 7, 2009, when 2,000 people marched from the Student Union Building to the farm, to show their support for retaining its existing size and location.

Later that year, the UBC Board of Governors stated that there would be no market housing on the farm provided that “the university’s housing, community development and endowment goals could be met through transferring density to other parts of campus.” The board also called for an academic plan for South Campus to advance “academically rigorous and globally significant” teaching and research around issues of sustainability.

By winter this plan – Cultivating Place – was in place and in 2011, following public consultation, the farm was re‑zoned “Green Academic” in UBC’s Land Use Plan.

As a result, the Centre for Sustainable Food Systems was soon established at the farm. It is a unique research centre that aims to understand and fundamentally transform local and global food systems towards a more sustainable, food‑secure future. There have been approximately 10‑15 active research projects on site every year since 2011.