I prank, therefore I am

At about 3:40 AM on February 5, 2001, a moving‑van stopped abruptly in the middle of the Golden Gate Bridge. Although it was still dark, witnesses said they saw around a dozen figures emerge and push a large object over the side of the bridge. They then reboarded the van, and sped away into the night. Nothing to see here. Move along.

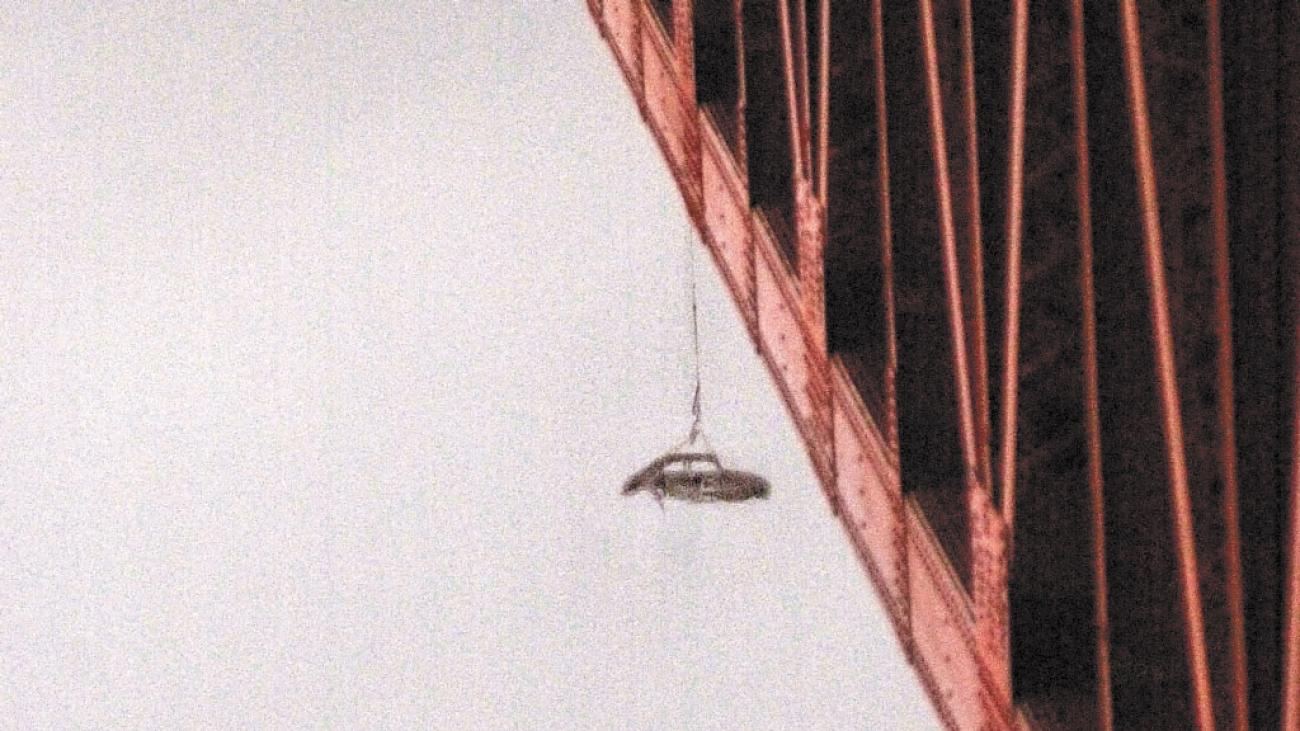

A couple of hours later, as the morning light began to filter through the thick fog that often envelops San Francisco, viewers at Vista Point on the north end of the Golden Gate could make out the silhouette of a red Volkswagen Beetle. It was dangling from the underside of the bridge, 10 storeys above the water. A Canadian flag was painted on one side of the car. A big red “E” was on the other side.

The stunt caused traffic jams and stopped ships from passing under the bridge for hours, while the US Coast Guard and California Highway Patrol puzzled over the Bug and how it got there. The feat had involved stringing a 27‑metre steel cable below the underside of one of the world’s most famous and photographed structures, somehow manoeuvring what appeared to be a 1970s vintage VW Bug (which weighs more than 1,600 lb.) into position beneath the bridge, and attaching it to the cable – all without anyone noticing.

At about 8:10 AM, the Highway Patrol cut the nylon cord holding the car to the steel cable, plunging it into the water below. It sank quickly to the bottom of San Francisco Bay. The story was on evening newscasts across North America and articles followed in newspapers the next day, from Miami to Britain, making this one of the most widely covered pranks of all time.

The police were infuriated by the chaos, and pledged to prosecute the perpetrators. They threatened fines and charges of criminal conspiracy and trespassing, possibly leading to jail time. “We’re pursuing every lead we have,” one Highway Patrol officer told the San Francisco Chronicle.

The most obvious lead: a press release faxed that morning to the San Francisco media by anonymous engineering students from UBC. They claimed that they had executed the stunt in order to “draw attention to the masterful feats of professional engineers and to celebrate the skills of the tradespeople who built the bridges.”

Canada’s engineering students have a long history of pranks, and this one may have been the greatest of all time. It was an exceptional technical challenge, its execution provoked awe and wonder, and the UBC students who carried it out did so in total secrecy.

The rich history of university stunts brings a wide spectrum of differing opinions about what a good prank is. Notorious American prankster and anarchist Abbie Hoffman identified three types of pranks: “‘good’ pranks,” he said, “were amusingly satirical, ‘bad’ ones gratuitously vindictive, and ‘neutral’ ones surreal and soft on the victim.” Hoffman’s classic example of a “good” prank occurred in 1967 when he and a group of activists threw fistfuls of dollar bills into the trading pit at the New York Stock Exchange. They managed to pause the ticker tape for six minutes while traders scrambled below: some booed, some chased the money. In 1971, Hoffman essentially pranked himself, publishing Steal This Book. Many readers took his advice; bookstores and the publisher were less amused.

For ample cases of the vindictive sort of prank, look to any university frosh week. They are often targeted against freshmen, rival disciplines, or competing universities. At the annual Yale‑Harvard football game in 2004, Yale University students, disguised as the non‑existent “Harvard Pep Squad,” distributed white and red placards to 1,800 unsuspecting Harvard fans. The fans were told that when they lifted the placards, they would spell “Go Harvard.” They actually spelled “We Suck.” Harvard fans, all sitting on the same side of the stands, were the only ones not in on the joke. Most didn’t know they’d been duped until reading the next day’s extensive media coverage.

The most diligent and technically ambitious university pranksters, however, are almost always engineering students. Stunts have become an engineering tradition, in part designed to show off the skills engineering students have learned from their education, which they consider much more valuable than a fluffy arts degree. The best engineering pranks go beyond being clever or poking fun. In the words of Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s anonymous Institute Historian T. F. Peterson (whose initials refer to the MIT engineering signature: IHTFP, or “I Hate This F–king Place”), engineering stunts require “accessing the inaccessible,” and “making possible the improbable.” An engineering signature – left on pranks across North America to identify engineering students as the tricksters – is ERTW, or “Engineers Rule the World.”

MIT claims to be one of the founding fathers of engineering pranks, with the first‑documented underground pranking society, the Dorm Goblin, established in the 1920s. Since then, cars and telephone booths have appeared on the roofs of campus domes and full‑sized sailboats in swimming pools.

Like the Yale “We Suck” stunt, engineering pranks are often aimed at rival institutions. But UBC’s pranksters have often set their sights beyond rival departments or universities and targeted more prominent victims, like government.

In 1978, after much planning, a trio of enterprising engineers broke into the British Columbia legislature in Victoria, entered the assembly chamber, and stole the Speaker’s ceremonial chair. A white concrete cairn with a red “E” – the signature of the UBC engineers – was left on the Speaker’s desk. The chair was returned a few weeks later. Over the years, UBC engineers have also stolen (and returned) the Rose Bowl trophy and Stanley Park’s Nine O’Clock gun. Hundreds of citizens who had gathered to see the return of the gun were outraged when the engineers threw it into the ocean, but that was part of the stunt: the dunked artillery piece was a decoy.

The individual identities of pranksters are closely guarded, as I discovered while pursuing the Golden Gate perpetrators. “The Engineering Undergraduate Society of UBC,” goes the group’s official statement, “has had, and continues to have, no knowledge regarding the planning of, execution of, or persons involved with any stunts past, present and future.”

Bruce Dunwoody, now an associate professor emeritus of engineering, first heard of the Golden Gate prank when he arrived at his office that Monday morning in 2001. His first phone call of the day was from a San Francisco radio station.

Dunwoody was careful not to admit culpability on air, but that didn’t stop authorities from trying to get information out of him. “I had someone phone me from the California Highway Patrol looking for a list of names of students so they could try to figure out who had done this by comparing the students to the list of people who had come into the States,” Dunwoody recalled. He refused to hand over the names without a request in writing.

“UBC proper had never been involved in [the stunt], as we never are,” said Dunwoody. But did he or UBC ever find out who was responsible for the act? “Let’s say we didn’t ask,” he said.

Dunwoody, who was an engineering student at UBC in the early ’70s before becoming a professor in 1985, thinks that creativity is the key to great pranks. His favourite prank occurred in the mid‑60s when a number of modern art sculptures mysteriously appeared on campus. “There was some questioning, but various folks chimed in that these were good and they became a part of UBC,” Dunwoody said. “Later on that year, the engineers went around with a sledgehammer and started smashing these things up, at which point there was great furor that the engineers were heathen sorts of people who didn’t appreciate fine art.” The engineers allowed the outrage to reach a climax, then introduced photographs showing that all of this supposedly fine modern art was nothing but junk they had created themselves. “At that point,” said Dunwoody, “everybody shut up real fast.”

Dunwoody argues that the sculpture stunt’s originality was what made it one of the best all‑time hoaxes. “A lot of pranks are the same thing as last year,” he said, and noted that the Golden Gate Bridge prank commemorated the 20th anniversary of the first VW Bug prank, when UBC engineers hung a car off Vancouver’s Lions Gate Bridge. “Without the creativity, it comes down to audacity and technical difficulty.”

While Canadian universities officially discourage pranks, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has practically incorporated pranking into the curriculum, believing that the technical ambition of most engineering stunts contributes to the students’ education. MIT pranks (which the school calls “hacks”) have become an establishment activity.

But at least one UBC engineering alumnus believes that MIT has nothing on UBC’s trickster traditions. I was put in touch with a graduate who, in the words of one blogger, “is legendary at UBC for taking 14 years to complete a normally four‑year bachelor’s program, and leading the ’Geers in their drunken tomfoolery for most of that span.”

“There is no rivalry,” said the engineer, who asked to be identified only as Yo. “No one else has taken this to the degree that we have.” He calls MIT’s pranks “not clever,” carried out on campus and without daring. For Yo, a great prank must appear difficult or impossible to the general public. Involving a famous landmark earns bonus points. But the most important part is the sense of accomplishment. “When you do something like this you are adding to decades of history,” he said. “It feels great to belong to this organization that has done these things in the past.” The stunts are also like advertisements for the department, according to Yo. “They say, ‘Hire a UBC engineer.’ ”

Engineering pranks are often aimed at rival institutions. But UBC’s pranksters have often set their sights beyond rival departments or universities and targeted more prominent victims, like government.

Yo claimed to know people directly involved in the Golden Gate prank but would not reveal their names. “Stunts are done in the name of UBC, not in the name of an individual,” he insisted, noting that some of the pranksters choose to stay silent to avoid liability or prosecution.

Cat Mills, a former UBC film student, can attest to the UBC pranksters’ combination of pride and secrecy. They agreed to participate in “Engineering Notoriety,” a short documentary on UBC engineering stunts she produced for a school project. She found that while her subjects agreed to speak in detail about many stunts, the pinnacle of pranking, the Golden Gate stunt itself, was almost always out of bounds. But not entirely. She managed to get some key information about the prank on tape. She allowed me to watch the film, which is not intended for public viewing, so long as I agreed not to identify those she interviewed.

So how did they suspend a Beetle from the Golden Gate Bridge? Some insight into the stunt can be garnered from details of the prank it commemorated, the hanging of a VW Beetle 20 years earlier from the Lions Gate Bridge in Vancouver. According to a former engineering society president from the 1980s interviewed in Mills’s film, that seminal stunt was carefully researched, and included retaining an engineering consulting firm to ensure that the weight of the car would not damage the bridge’s support beams.

However, as US authorities involved in the Golden Gate stunt discovered, the weight dangling from the nylon cord was not as significant as it appeared: the vehicles hung from the Golden Gate and Lions Gate bridges were only shells, the heavy engines, wheels and windows having been removed. “A group of us tore down a Volkswagen in a basement,” an engineering alumnus from the 1980s says in the film, recalling an earlier VW experience. In what was apparently UBC’s first successful stunt involving a Beetle, he and three accomplices placed a car on the top of the university’s Ladner Clock Tower. “We pulled the two halves of the Volkswagen up either side,” he told Mills, “and bolted it together on the top.”

Since the Lions Gate stunt, vintage VW Bugs have been spotted hanging from almost every bridge in the Vancouver area, the Massey Tunnel, and the wooden rollercoaster at the Pacific National Exhibition.

The Golden Gate prank may also have been a two‑step, two‑day ordeal. The original Lions Gate stunt was. On the first day, according to the former engineering society president, a steel cable was hung in a loop from the support girders underneath the bridge. The loop was then clipped to the handrail for easy access. Attaching the cable required a delicate touch to avoid triggering an alarm, but once it was in place it was barely visible. On the second day, the students were given an unlikely gift: a minor car accident on the bridge stalled traffic. The traffic jam gave them just enough time to remove the shell of the VW from their flatbed truck, unclip the cable from the handrail, attach it to the car, and throw it over the side of the bridge – all in just minutes.

Since the Lions Gate stunt, vintage VW Bugs have been spotted hanging from almost every bridge in the Vancouver area, the Massey Tunnel, and the wooden rollercoaster at the Pacific National Exhibition. The preceding 20 years of experience must have contributed to the success of the most challenging part of the Golden Gate stunt: slinging a 27‑metre cable under the bridge in advance, without detection.

In the film, an engineering student says that the team that laid the San Francisco cable stayed in hiding under the bridge for an entire day, waiting for the moving‑van to arrive under the veil of darkness. When the van drove up, they quickly clipped the nylon cord and let the Bug drop.

The UBC engineers who hit the Golden Gate had also apparently originally planned for this to be a simultaneous, two‑city prank, with a second Bug to have been hung from the Lions Gate Bridge. The Vancouver end of the plan was foiled when students triggered sensors on the crossing, and were discovered by the RCMP.

Though I spoke to a number of engineers who claimed to have knowledge of the event, no one ever admitted to being a Golden Gate prankster. And I suspected that, of all of those I spoke to, Yo had the most inside knowledge of the stunt. So, exasperated, I asked one more time: how the hell did they get the 27‑metre cable under the bridge? “Oh,” said Yo, slightly surprised by my question, “that was the easy part.”

The original version of this article was written by Erin Millar for Maclean’s Magazine in 2007.