The Clock Tower and the Anarchists

The Ladner Clock Tower is a well‑established landmark of UBC’s Vancouver campus, but when first proposed in the 1960s, as with many things during that era, it was the focus of controversy.

The tower was a gift from Leon J. Ladner. He was the son of British Columbia pioneers, born and raised in the town that bears his family name. He went on to co‑found the prominent law firm Ladner Downs and served as an MP from 1921 to 1930. Ladner was also a long‑time supporter of the university. A founding member of Convocation, it was Ladner who in May 1921 moved the resolution urging the establishment of a new campus at Point Grey. He was also a member of Senate from 1955 to 1961, and of the Board of Governors from 1957 to 1966.

In a letter to UBC President John B. Macdonald, dated 4 July 1966, Leon Ladner announced his gift of $100,000 (later increased to $150,000) for the construction of a clock and bell tower. He intended it as a tribute to the founding pioneers of the province – in particular his father and uncle, Thomas and William Ladner. He also hoped that the clock tower would serve as an inspiration to UBC students:

When that clock tower is completed and the clock rings out the passing of each hour, I hope it will remind the young students that not only does time go fast, but that the hours at our university are very precious and the use of those hours will seriously affect the success, the happiness and the future of their lives.

The project was officially announced by the university in July 1967. According to the press release, the clock was originally envisioned at the top of the new administration building planned for the corner of University Boulevard and Wesbrook Crescent. Ladner felt the building’s proposed eight storeys would make it the ideal location. When the university determined that funds were available only for a four‑storey administration building, Ladner agreed to an alternative site immediately west of Main Library.

The tower’s design was the result of a competition held by the university architectural firm Thompson, Berwick and Pratt. From among 10 submissions submitted by the staff, Ladner and two of the firm’s executives picked a proposal by Ray Griffin. He was a 29‑year‑old architect who had received his Bachelor of Architecture degree from UBC in 1961 and had been with Thompson, Berwick and Pratt for four years.

Griffin’s plans called for a 140‑foot‑tall four‑sided carillon tower, with seven‑foot clock‑faces at the top of each side that would be illuminated at night. Together with light projected through coloured glass in vertical slits down the sides of the tower, the clock was intended to catch the attention of passers‑by around campus as well as seafarers on the waters off Point Grey.

The carillon consisted of 330 bells, including 61 Flemish bells, 61 harp bells, 61 celeste bells, 61 quadra bells, 61 minor tierce bells and 25 English tuned bells. The “bells” were actually small bronze bars, made from the same metal as traditional cast bells. When the bars were struck with small metal hammers, the sound would be amplified from the top of the tower through 12 speakers.

The design also included a 100‑seat terrace fitted into the natural contours of the surrounding landscape, where spectators could sit and watch musicians play the carillon using a console or keyboard. This part of the project was later abandoned. The console was installed in a small concrete building beside the tower. The carillon could be played manually from the console, or automatically using nylon rolls with holes punched in them, similar to those used on old‑fashioned player pianos. In 1997, this carillon would be replaced by a digital system capable of playing a wide range of synthesized bell sounds.

Soon after it was announced, some students questioned the appropriateness of Ladner’s gift. In October 1967, The Ubyssey reported that newly‑elected undergraduate student senators were asking if the money could be “diverted into more urgent projects, such as the library.” The response from the university administration was that the funds could not be used for anything else.

For student activists, the issue still wasn’t settled. In The Ubyssey on 27 October 1967, an article by Donald Gutstein began, “What could you do with $150,000 at UBC? You could buy 25,000 books. You could give $8 to every student. Or, better still, you could throw it away. You could build a clock and bell tower next to the UBC library.”

Gutstein called the clock tower “a functional, social and visual irrelevancy” – it had no value as a landmark, and reduced the multi‑use function of the space in front of Main Library. It was “junk,” useful only for filling some of the wasted space between buildings. He complained of “the monotonous and inconsequential tolling of the hours, hour after hour, day after day, year after year, century after century” that the clock would bring to the campus.

Finally, Gutstein objected to Ladner’s idea that the clock’s chimes would remind students that “the use of [their] hours [at UBC] will seriously affect the success, the happiness and the future of their lives.” To a representative of the late‑60s counter‑culture, this was a thinly‑veiled demand for conformity. “The clock tower is a large Pavlovian‑type experiment”, he wrote. “Ring the bell enough times until we react ready for the business world.”

Other students contented themselves with poking fun at the tower. Off‑colour jokes about the “lofty erection” abounded. The Ubyssey quoted graffiti in Main Library that read, “I resent that tower; it reminds me of my short‑comings.”

Leon Ladner was dismayed and disappointed by the response to the project. He insisted that a memorial to the pioneers of the province was an appropriate use of his money. “There are no memorials in B.C. to honour the early builders of this province and I take it upon myself to do this,” he told The Ubyssey in 1968. “Nobody, particularly 20,000 students, will agree upon the best form of a memorial... [T]he donor should have a say in the disposition of his contribution.”

Ladner dismissed the idea of using the money for books, saying, “books are the provincial government’s responsibility.” He also pointed out that he had already established two scholarships at UBC; that he had promised another gift for the new Student Union Building; and that his other education‑related foundations and gifts amounted to $30,000.

Ladner also claimed that he consulted with student leaders, both after his initial offer to the university and during the initial planning stages. Peter Braund, former AMS president (1966‑67) had a different perspective, recalling that the consultation was rather limited. “He just told us one afternoon over lunch that we are going to have the tower. It wasn’t a consultation,” he told The Ubyssey. The students’ respect for Ladner, however, prevented them from making any objections at the time. “We didn’t indicate our opposition because he’d done a great deal for the university,” said Braund.

Other opponents of the clock tower resorted to more direct action. In October 1968 a man was arrested while vandalizing the tower. The official report noted that locks had been forced open, some light fixtures broken, and the concrete structure spray‑painted. The incident occurred the same week as the student occupation of the Faculty Club, although there was no documented connection between the two events. In a letter to acting university president Walter Gage dated October 28, Leon Ladner expressed his outrage:

If the authorities are reluctant to lay the [vandalism charge], I am prepared to lay it myself...

In my judgement, public opinion will react strongly against our University and our student body if vandals, like this man, are not prosecuted or expelled. Public opinion is already building up a strong critical attitude towards the student body without recognizing the fact that 95 or 98% of the students are decent, good people.

Despite such opposition, construction of the tower proceeded and was largely complete by the end of 1968. The student radicalism did not abate and the generally tense atmosphere around the campus made both Ladner and the university administration reluctant to schedule a public dedication ceremony. As President Kenneth Hare wrote to Ladner on 29 November, “the fact remains that until we completely suppress the radical fringe – and this is in progress – it is very foolish to give them any opportunity of raising a crowd where they can make a political demonstration.” Director of Ceremonies Malcolm McGregor was even more blunt – when asked by The Ubyssey when students could expect an official dedication, he answered, “I won’t be part of a ceremony that is for the benefit of anarchists.”

A modest ceremony proposed for December 1968 – which would have coincided with the Christmas exam period – was not approved as the administration felt that it would be an added inconvenience for students. Another proposal to have a dedication and carillon recital during the spring 1969 congregation also went nowhere.

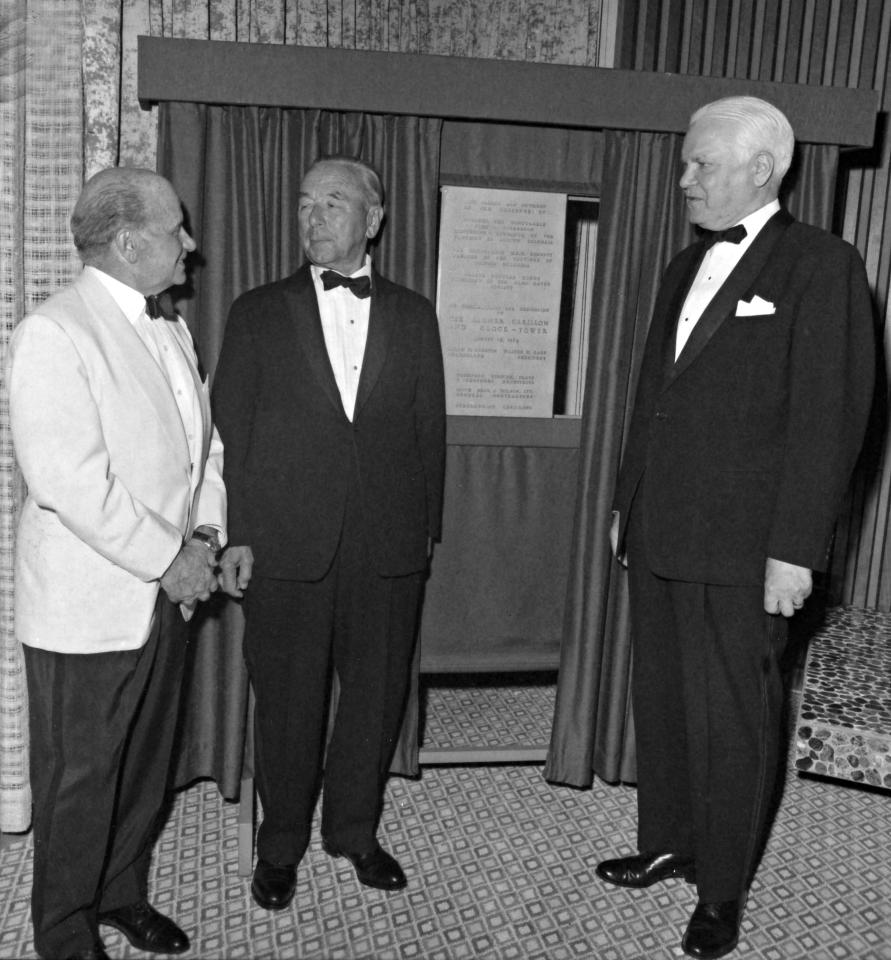

Finally, a dinner party was held on 19 August 1969 to honour Leon Ladner and his gift to UBC. Guests included Premier W.A.C. Bennett, Lt.‑Gov. John Nicholson, and some 40 other invited guests. The affair was not publicized, and guests were specifically requested not to make any public statements about it. After dinner, Ladner made a brief speech, unveiled a commemorative plaque, and officially presented the tower and carillon to the university. On a pre‑arranged signal from a campus patrolman, Hugh McLean from the Department of Music began a short recital at the carillon. The music could be heard across campus.

Over the years, the controversies surrounding the building of the Ladner Clock Tower have gradually faded away. Music broadcast from the tower has become a traditional part of congregation ceremonies every spring and fall. It is still the butt of jokes, particularly in The Ubyssey, which has published pictures of the tower with a condom drawn over it on at least one occasion. But to most students, faculty and alumni, it is part of the campus landscape, and if anything is viewed positively – even with affection.