UBC’s King of Cult

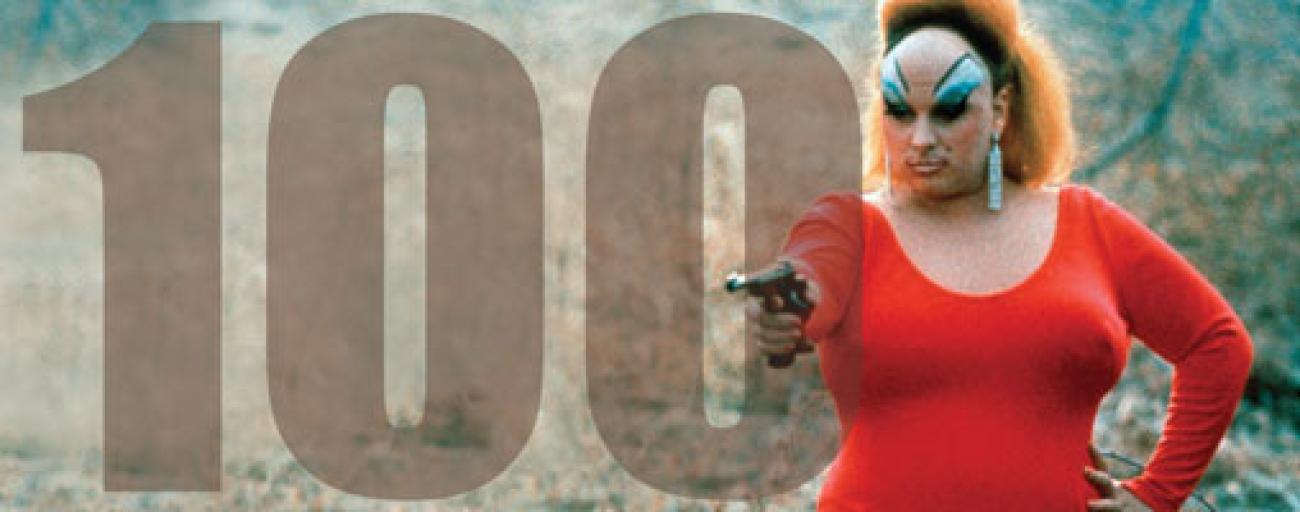

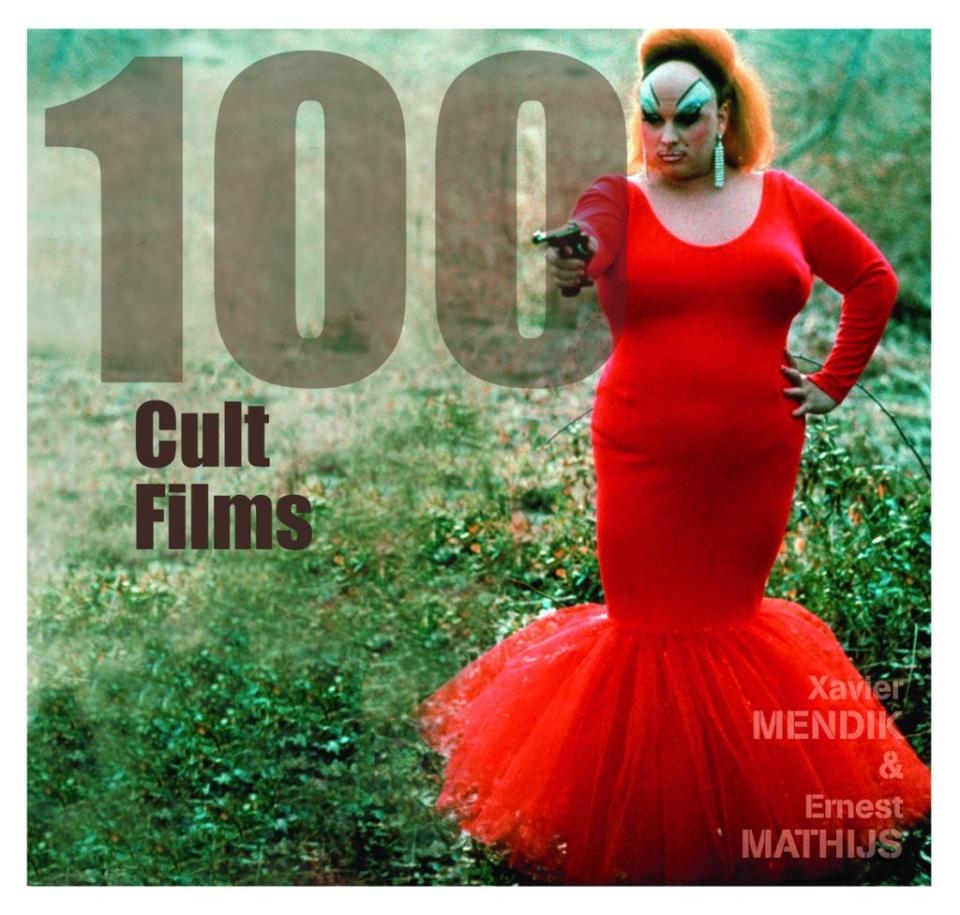

The front cover of Ernest Mathijs’ latest book, 100 Cult Films, is dominated by a hefty drag queen in a bulging scarlet gown. One hand is on her hip, the other is pointing a revolver. Garish blue eye shadow is plastered well up her forehead and onto a shaved scalp. To film buffs, she’s instantly identifiable: it’s Divine starring in John Water’s notorious cult classic Pink Flamingos.

The movie first jarred viewers in 1972 with an unforgettable feast of filth: perverse desires, cannibalism, vile eats, and a singing anus. Forty years later, it remains an icon of the cult-film phenomenon and is still shocking enough that Mathijs, a professor of film studies at UBC, will not show his students certain scenes. As head of the department’s Centre for Cinema Studies, he has the enviable job of watching movies, and teaching and writing about them. His particular passion lies with a select number of films that, like Pink Flamingos, so disrupt conventions or challenge expectations that they inspire an ardent following.

Alongside Cannibal Holocaust and Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom (reputedly the sickest movie ever made), readers will find less cringe-inducing movies, such as The Wizard of Oz and Casablanca.

100 Cult Films (co-authored with Xavier Mendik) certainly includes a healthy dose of the classic nasties. But alongside Cannibal Holocaust and Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom (reputedly the sickest movie ever made), readers will find less cringe-inducing movies, such as The Wizard of Oz and Casablanca. From torture films, horror, and pornography to campy delights, anime, Hollywood glamour, and a 1922 Swedish pseudo-documentary about witchcraft, 100 Cult Films includes nearly eight decades of films from almost every genre. So what, if anything, defines a cult film?

Shock value has unquestionably propelled more than a few films into cult notoriety – with censorship perhaps adding to the appeal. More often than not, cult films are too challenging, bizarre, or ambiguous for mainstream tastes. They can be badly, even disastrously, acted and produced. They are often commercial failures. They deal with subjects no one wants to talk about. But for some reason they persist , or ripen decades later into a cult classic.

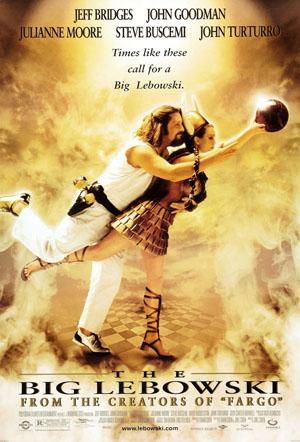

Devotees attend Star Wars conventions. They appear at The Rocky Horror Picture Show screenings dressed in black corsets and fishnets. They drink White Russian cocktails in deference to The Big Lebowski.

Ernest Mathijs’ course on cult cinema offers “an overview of the weird and wonderful world of cult films. It explores the fandom, subcultures, controversies, and viewing rituals around offbeat art films, transgressive film, exploitation movies, body horror, martial arts, camp musicals, midnight movies and 'badfilms' (the worst films ever). Screened materials include Blade Runner, Donnie Darko, The Room, Casablanca, Enter the Dragon, and Dirty Dancing."

The real question, Mathijs suggests, is not what defines a cult film, but what inspires a cult following. Many movies have all the criteria common to cult films, yet fail to inspire any devotion. “Cult films are not cult by design,” he explains. “They are cult by reputation and reception.”

Devotees attend Star Wars conventions. They appear at The Rocky Horror Picture Show screenings dressed in black corsets and fishnets. They drink White Russian cocktails in deference to The Big Lebowski. They talk back to the screen, repeat catch phrases, take pilgrimages to shoot locations, watch, rewind, and watch again. What unites films as diverse as The Sound of Music and Café Flesh is the emotional experience of their devotees. As the world “cult” suggests, followers undergo a very personal initiation into a collective experience of ritualistic celebration.

Almost by definition, the cult experience is highly subjective. Not everyone will “get” every film. Take the Big Lebowski, for example, a popular film with many of Mathijs’ students. “It becomes like a secret handshake,” says Mathijs. “They can talk the dialogue for hours. There is a deep intimate attachment between ... people via that film.” As a scholar, Mathijs can see it objectively as a cult film, but emotionally the film doesn’t work for him. “My students tell me, you don’t ‘get’ The Big Lebowski, which is true. I don’t get it. But I get other films.”

A hip and energetic professor in his early forties with the exuberance of a lifelong film buff, Mathijs is one of the initiated — which is to say he understands what it’s like to see a film that so defied all expectations it seemed to speak directly to him. For Mathijs that film was Canadian director David Cronenberg’s Videodrome.

A large poster of Videodrome hangs on the wall beside Mathijs’ desk. The movie still has its hold on him, and that deep emotional attachment between a film and its devotees is at the heart of his fascination with cult.

The movie that Andy Warhol called “the Clockwork Orange of the 1980s,” Videodrome is a hallucinatory descent into a dystopic world of living televisions, sadomasochism, pornography, murder, and media control. In fact, test audiences reacted so adversely to its horrific imagery the film almost wasn’t released at all. Like many cult films, it was a box office failure. But this was the early 1980s when video stores first appeared, and Mathijs was in his teens.

At first he explored the shelves of horror movies because they seemed edgy. “But after you’ve seen four or five horror films, you get the formula; you know how they are going to work so they become cliché and mainstream.” Then he saw Videodrome. It was as if the film had reached out to him and a spark ignited. For Mathijs, who grew up in a small Belgium town, Canadian horror was as exotic as Kung Fu movies and infinitely more mesmerizing. In finding his film, Mathijs found his niche. He went on to study film and completed a PhD at the University of Brussels. His thesis? The cultural reception of Cronenberg’s films.

A large poster of Videodrome hangs on the wall beside Mathijs’ desk. The movie still has its hold on him, and that deep emotional attachment between a film and its devotees is at the heart of his fascination with cult. It is also the focal point of his latest research project, “Hot, Cool or Cult?” funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The project aims to determine what cult cinema means within popular culture. The classic definition of cult film as a bad or badly-made movie that often offended and usually bombed is challenged by films such as The Twilight Saga and Titanic which have claimed cult status despite their mainstream popularity. Are the original boundaries of cult being redrawn? Are the classics more authentic? For Mathijs, it’s all up to the fans.

He has singled out five recent movies that have the potential to become cult favorites: Paranormal Activity, In Bruges, Splice, The Social Network, and Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn. They all have at least some of the tropes affiliated with cult cinema such as quotable dialogue, offensive language, horror, special effects, strange bodily mutations, and unpleasant body fluids. If you’ve seen any of the movies, you’ll most certainly have an opinion. Mathijs has posted questionnaires online.

Hot, Cool or Cult?

Film Studies professor Ernest Mathijs wants your opinions on five recent movies that all have at least some of the tropes affiliated with cult cinema -- such as quotable dialogue, offensive language, horror, special effects, strange bodily mutations, and unpleasant body fluids. If you’ve seen any of the movies, you’ll most certainly have an opinion. Online questionnaires can be found here.

But will they become cult films? Only time will tell. To become a true cult classic, a movie must endear itself to future generations of fans who can find some new and relevant meaning in it. Along with the highly entertaining descriptions of plot and main themes, 100 Cult Films relates the twists and turns of each movie’s reception through history. Casablanca was forgotten until Humphrey Bogart’s death, after which it developed a devoted following who embraced the film’s nostalgia. Screenings were transformed into ritual events as fans shouted “here’s looking at you kid” and “we’ll always have Paris.” Likewise The Sound of Music became a pioneer of participatory sing-alongs during a karaoke-type screening at the 1999 London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. Manos, the Hands of Fate was forgotten until it was rediscovered by a cult fascination in really bad films. Their cultish reception has warped far from the movies’ planned orbits but only because the movies have continued to speak to fans and ignite devotion.

And then there are the classic nasties like Pink Flamingos. The film remains matchless and still offers a provocative and unique viewing experience. And that is really the point: films that inspire cult followings offer a totally and enigmatically singular encounter in a way no other film could ever achieve again.

Whether a film is critically panned, banned, or a blockbuster, whether its actors are iconic, the imagery is offensive, nostalgic, or syrupy, ultimately a cult movie has that enigmatic power to resonate with fans so deeply and personally that they call the film their own. So what about Mathijs’ film, Videodrome? Almost three decades old, will its cult status stand the test of time? Mathijs could hardly say no. But as a scholar of cult he can only observe that, as with any other film, “Videodrome will retain its enigma as long as its cult fans perceive it as such.”