People rallied at the Michigan State Capitol in February to oppose the US administration – one of many similar protests held across the US. (Photo by: Jim West/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Democracy: Down, but not out

Despite the backsliding, public support for democracy remains strong.

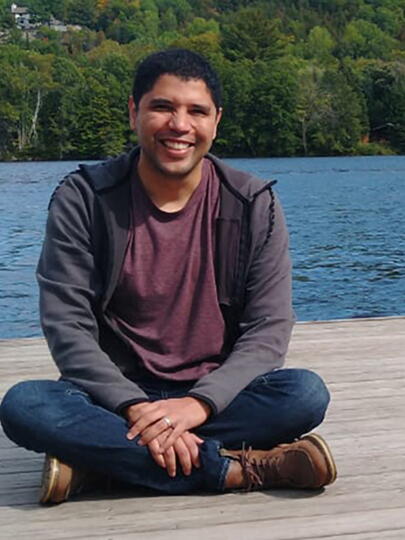

In times of stress – and these are stressful times – it’s a privilege to be able to check in with an expert to confirm whether your anxiety is even valid. So it’s good to be sitting across the table from Lisa Sundstrom, a UBC professor of political science who has been researching democracy and its challenges around the world for decades. Here is someone who will understand the worst, and know the best. But it’s bad when her opening comment on the state of that apparently fragile form of governance is: “I find myself banging my head on my desk.”

Sundstrom isn’t just responding to the latest unnerving headlines. Rather, she points out that the US-based Freedom House, which tracks the state of democracy around the world, opened its last annual report by saying that in 2023, “Flawed elections and armed conflict contributed to the 18th year of democratic decline.

Mark Warren, a UBC professor emeritus and the immediate past president of the American Political Science Association (APSA), is similarly trepidatious. He adds that, as far back as 2016, the Economist Intelligence Unit had demoted America itself to the status of a “flawed democracy.” And that was before Donald Trump resumed the presidency and immediately pardoned the many hundreds of mob members who had violently challenged the legitimate results of the previous election.

Sundstrom, however, won’t let the conversation rest on a negative. Much as the current state of democracy has a worst-ever feel to it, she notes that in 1973, when Freedom House published its first assessment of global political rights and civil liberties, it found only 44 of 148 countries to be “free,” whereas the count has climbed to 84 free countries out of 195 on the modern list. Freedom House declares: “The primary finding from 50 years of Freedom in the World analysis is that the demand for freedom is universal, and not even the most sophisticated and brutal crackdowns have succeeded in extinguishing it.”

It’s important, in setting the context for this discussion, to register the case that democracy is, objectively, a good thing. As Warren says, the research is clear: “Strong democracies tend to be healthier, happier, more innovative, wealthier, less violent, less corrupt, more pluralistic and tolerant, better for women and minorities, and more attentive to the worst off.”

Sundstrom, too, has long embraced the case for democracy, having built her whole career on what now appears to have been a high watermark in democratic achievement. The daughter of a high school history teacher in Ucluelet, BC, Sundstrom landed at the University of Victoria in 1989 – the year that the emboldened citizens of Germany pulled down the Berlin Wall, marking a ceremonial end to the Cold War between the democratic forces of the West and the repressive regime of the shattered Soviet Union. Buoyed by the spirit of Perestroika – of restructuring – Sundstrom decided to major in political science, started studying Russian, and in her third year moved to Moscow.

“It was very exciting,” she says. “Nothing worked, and there was nothing in the stores, but the people were wonderful – very poor but very hopeful.”

The whole world seemed hopeful, Sundstrom says. “After the Cold War, democracy had so much momentum – the influence of those ideas.” People everywhere seemed to agree that “to become a player on the world stage, you did it by joining the club of democracy.”

Sundstrom moved on to Stanford University for a PhD, but she continued to focus on Russia, writing her dissertation on civil society and the rights of Russian soldiers and women. So she watched with personal concern and professional curiosity as the country struggled with its nascent democratic status. “It’s not that Russia was ever successfully a fully fledged democracy, but I was still hopeful.”

Then came the rule of Vladimir Putin, who emerged as acting president on the last day of 1999 and has, in one guise or another, ruled Russia ever since. It was during his first decade in power, Sundstrom says, that “elections became performative” – to the point that, in the last decade, no independent monitor would call a Russian election fair.

The democratic backsliding was also spreading. Just as Putin initially won over the Russian people by saying, “The West cheated us and stole our wealth; don’t rock the boat, and I’ll make things better,” Sundstrom says that Hugo Chávez eked out his early and legitimate electoral victories in Venezuela in 1998 by declaring that the system was broken and that he and his movement alone could fix it by destroying the nation’s internal enemies – a line that echoes with disturbing familiarity today. As the new century unfolded, other examples of democratic degradation followed, including in Poland, Italy, and particularly Hungary.

Warren addressed this notion in a keynote address to the APSA last September, saying that, while a few African democracies have been overthrown violently in the past decade (Zimbabwe in 2017, Sudan and Mali in 2021, Chad in 2022), “Today, resurgent authoritarianism is rarely the result of military coups, but rather the work of political elites who have won elections [or made significant gains], from Trump and [Hungary’s President Viktor] Orbàn to Poland’s Law and Justice, the Alternative for Germany, and France’s National Rally.”

“The demand for freedom is universal, and not even the most sophisticated and brutal crackdowns have succeeded in extinguishing it.” ~ Freedom House, US

It appears, then, that, for at least some of the people some of the time, “electoral institutions are failing to reflect the democratic values of citizens, and in some cases actively undermining them.” Examining that systemic failure, Warren identifies five “structural causes of discontent” within developed democracies. They are:

Globalization – which can separate workers from the wealth they create and voters from the people who make decisions that affect their lives;

Economic inequality – which undermines the majority’s faith that the electoral system is fairly representing their interests;

Cultural polarization – which is driving a wedge between younger, more racially and ethnically diverse majorities in dynamic urban areas and older conservative voters often concentrated in rural areas. The latter are more vulnerable to what political scientists call status insecurity and have been convinced to lash back against the imperatives of diversity, equity, and inclusion, which they believe are being used to undermine not just their privileges but their rights. Warren notes that, “Other writers have postulated that the 2016 election of Trump was, at least in part, a backlash to rapid and progressive cultural change, represented politically by the election of Obama in 2008 and re-election in 2012;”

Social media (now AI enhanced) – which is unedited, largely ungoverned, and therefore fertile ground for both domestic political entrepreneurs and foreign mischief-makers who organize, spread rumors and misinformation, and manipulate voters; and

Polarization – in which people live increasingly in what political scientists call “epistemic bubbles” – echo chambers of algorithmically curated input that is more likely to reinforce people’s biases than broaden their horizons. Warren says, “We should worry about polarization because it signals that adversaries are becoming enemies, and enemies are less likely to deal with conflict peacefully…. Democracy, of course, fails if it cannot channel conflict away from violence and into talking and voting.”

Sundstrom offers a sixth factor undermining democracy – something circumstantial rather than structural, but powerful nevertheless: COVID. With everyone locked in their homes, reduced to doom-scrolling on their cellphones, “everything was more inflammatory,” she says. “People were afraid and resentful of government. There was a disengagement from collective solutions.”

School of Journalism professor Peter Klein also weighs in, saying that, in addition to the rise in social media, we are suffering from a decline in traditional media. He names in particular the major US television networks NBC, ABC, CBS, and PBS, which, like CBC and CTV, were virtual public squares where the whole population was once exposed to a common set of facts. Warren agrees, noting that even before the algorithm-generated bubbles on social media, informational self-selection was breaking out with cable television, “the first post-war medium to segment audiences.”

When we stop listening to one another, it reduces the chances that we will speak with understanding or even respect.

“No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

This is Winston Churchill, a quote almost everyone knows, even if many people sometimes forget its import – like the pro-Brexit voters in the UK who in 2016 were happy enough to vote against an imperfect democratic compact with the European Union without having identified a preferable alternative.

Yet, despite the backsliding, Warren says that public support for democracy remains strong. “The World Values Survey shows that overwhelming majorities in the democracies rank the ‘importance of democracy’ very highly, even when they are disappointed with how ‘democracy’ works in their own countries.” He adds, “Even populist authoritarians claim that they represent democratic values, against elitist legislatures, courts, and bureaucracies.”

The question, then, turns to solutions, which is a specialty for Warren, a long-time scholar of democratic innovations. He was co-founder in 2011 of a project called Participedia, a crowd-sourced, open-access online platform that is now the world’s largest database of democratic innovations; it currently lists more than 2,200 examples in 159 countries.

Democratic innovations generally refer to practices and institutions that deepen or widen democracy; fall outside of the older, legacy institutions; and supplement rather than replace these institutions. They usually involve the participation of ordinary citizens, new forms of representation, and learning and deliberation by citizens and public officials alike. And many innovations have proved to be effective at resolving local issues. Overall, however, Warren says the gains are usually “modest and incremental.” The easy fixes are local, even if the biggest problems are global.

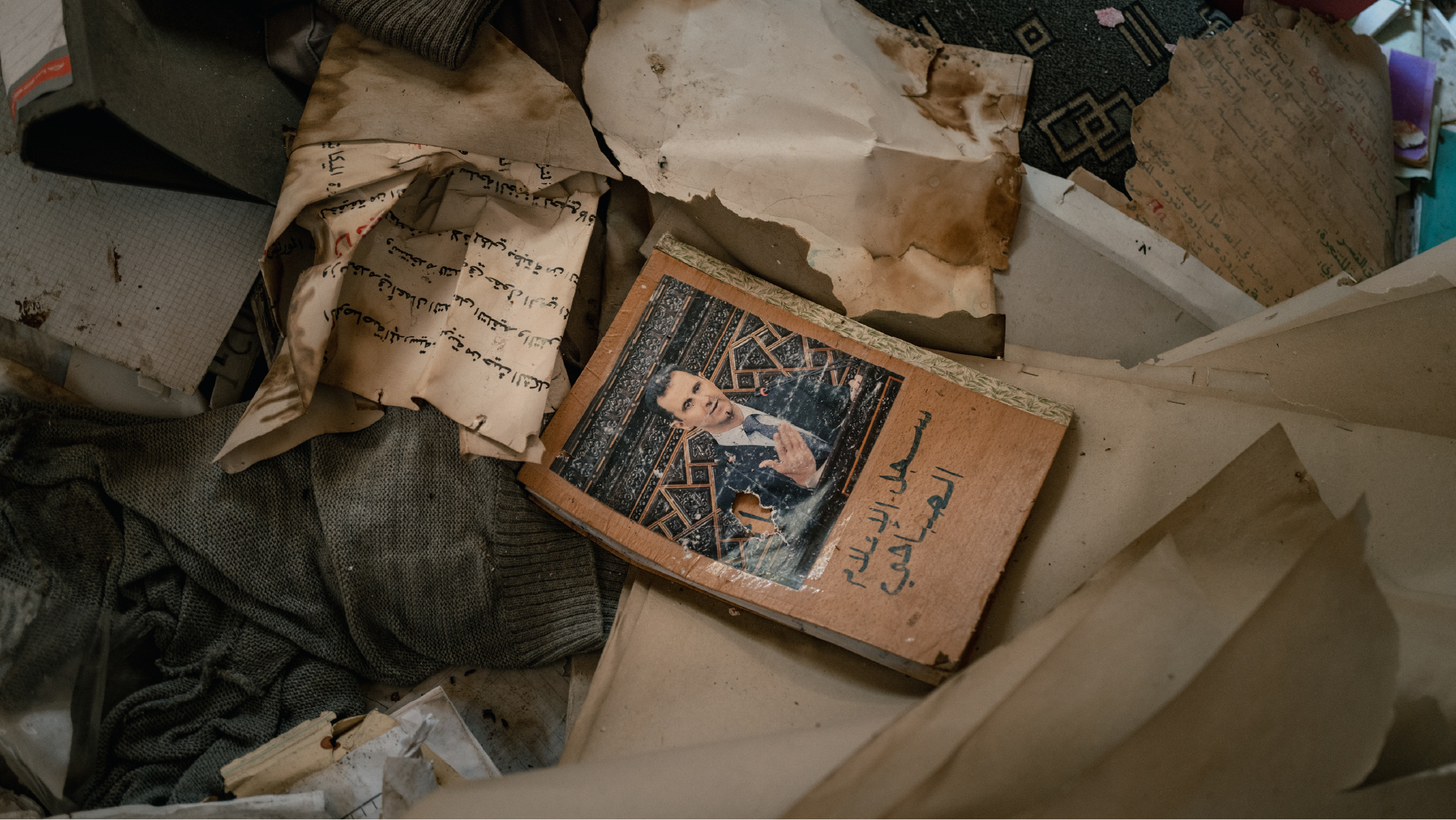

Sundstrom, who was recently appointed Associate VP of Research and Innovation, looks hard for the bright spots. In the last year, for example, we have seen the overthrow of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, one of the Middle East’s most toxic autocrats, though Sundstrom acknowledges that the Syrian situation could easily devolve into rule by another equally autocratic force, as has happened in Afghanistan and elsewhere.

Given her background, Sundstrom also marvels at the continuing resistance in Russia, especially the actions of the Feminist Anti-war Resistance network, which is forever doing what she describes as “sneaky things” – such as writing anti-war slogans on ruble banknotes or carrying flowers in Ukraine’s yellow and blue – gestures designed to unsettle President Putin without, perhaps, being enough to get protesters arrested.

She is also hopeful for a post-war Ukraine where, even in the increasingly autocratic decade before the Russian attack, there had been “two big uprisings, very democratically driven.” Sundstrom says, “I’m a people-power thinker. There is always a chance when people stand up.”

Beyond this, looking to the United States, she says, “If political elites finally resist and stand up, then we’ll be okay.” And if “we’re not seeing that now,” there is potential for resistance in the courts, and “I still have a little faith in the US Supreme Court, that they will rule against total expansion of executive power.”

In conclusion, and clinging to the hopeful approach that has marked her career, Sundstrom settles on two points. First: “The longest-standing democracies tend to be the most stable in the face of crises;” and second, “Dictatorships tend to look very strong, until suddenly they’re not.”

“Look at the long sweep of democracy – always with two steps forward and one back,” she says. “Every time it gets a little further.”