Flawed foreign ownership narratives drove "housing nationalism" in Canada

The number of BC homes owned by people who live outside of Canada is less than half the number of homes that BC residents own abroad.

If that surprises you, blame narratives that have arisen during the housing affordability crisis, which often cite foreign home ownership as a major contributing factor with little evidence.

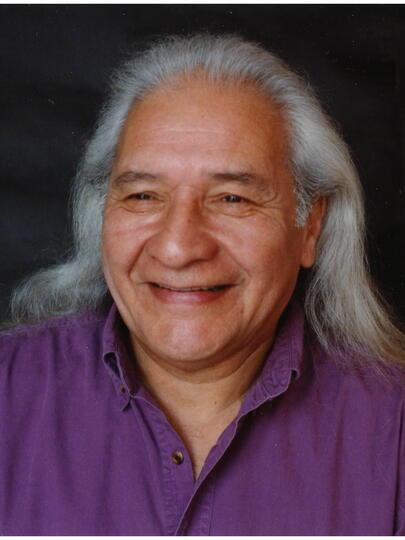

This is a form of nationalism that UBC sociologist Dr. Nathan Lauster and co-author Dr. Jens von Bergmann call “reactionary housing nationalism.” Their new paper in Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies explores the trend and reveals more surprising statistics. We spoke with them about the research.

What do you mean by "reactionary housing nationalism"?

Nathan Lauster: We understand reactionary nationalism as a strategic framing of problems, taking of positions, and construction of solutions that blame or demonize the foreign while valorizing membership in the nation.

Nationalism has mostly been talked about as a jobs issue, or a wartime issue where minorities in one country are associated with the enemy country during a trade war or a military war. Then you see these nationalist responses where minorities suffer.

But I think housing should now be added to this. We’re not just seeing this in Canada — we’re seeing it all over the place.

When did it occur to you that this was taking hold in Canada — and in Vancouver in particular?

NL: For me it was during the run-up in house prices between 2014 and 2016, when the discussion shifted rapidly to foreign buyers as drivers — especially from China. Jens and I separately began to track and question this evolving narrative that foreign buyers were to blame. It didn’t seem very well supported.

What troubled you about this trend?

Jens von Bergmann: I remember distinctly having a beer with a friend, a second-generation immigrant from Hong Kong. He was telling me about opening the door to his house on the west side and people looking at him strangely, as though questioning his living in this house on the west side. It felt really odd to me, because I am an immigrant. I grew up in Germany and immigrated to Canada via the US. He was born here, grew up here, did everything here — but he’s the one who felt like a foreigner.

NL: Blaming foreigners for problems rapidly blossoms into this increasing cast of potential villains who can be really flexibly defined as foreign. It can come down to race, whether or not you’re a permanent resident, whether you’ve just arrived, or where your money comes from. It generates all kinds of possible sources of who foreign could be, and I think that’s really dangerous.

What does your research reveal about some of the myths and narratives that took hold in this environment?

NL: One of our goals was to track how housing nationalism arose and made its way from Vancouver into national policy, and another was to pull together data sets that could establish a baseline for understanding transnational property ownership involving Canada.

JVB: We’ve seen that there are about twice as many properties that residents of BC own abroad than residents abroad own in BC. This challenges and contextualizes the narrative that it’s all about the foreign money coming into our real estate market. It’s really just transnational ties, and flows that go either way. Similarly, if we look at the number of homes here that are owned by people who live abroad, about half of them are Canadians or permanent residents.

What if Canadians are contributing to housing crises in other countries?

NL: Housing nationalism may provoke a response in places where we see pushback against Canadians owning properties abroad. That can have all kinds of effects. If Canadians were to remove their capital from abroad and invest it back into Canada, that could further increase our affordability issues in places where we lack supply. So there’s no great solution that’s related to penalizing foreignness on either side. Instead, we probably want to look at things like empty homes taxes, but also building a lot more and making supply more responsive to where people want to live.