Tackling toxic drugs

UBCO’s collaboration with the community is breaking down barriers when it comes to accessing harm reduction services.

A student nervously knocks on the door before entering. She is soon greeted and ushered into the room by second-year nursing student Adrian Van De Mosselaer.

“I’m here to get my drugs checked,” the student says quietly as she pulls a small package out of her pocket. She hands it to Van De Mosselaer, who — as a student himself — understands all too well the complex feelings students experience when deciding to get their drugs checked.

“A lot of people are nervous coming in. They may be excelling in school and are afraid of the academic repercussions of taking drugs, or they may be going through a difficult time in life and want to ensure they’re using drugs in a lower-risk manner,” he explains.

“Our ultimate goal is to get the word out that it’s ok to get your drugs checked. We really want to facilitate opportunities to sit down with students and have an open dialogue about drugs, so we can reduce the stigma as much as possible. We want to be known as a place where students can safely get their drugs checked and then go from there.”

It’s all part of a program run by HaRT (Harm Reduction Team), which is supported through collaborations with UBCO, Interior Health, the BC Centre on Substance Use, and the local community. HaRT enables students to access free harm reduction services on campus and in the community, including drug checking with a spectrometer and test strips, single-use injection and inhalation supplies, workshops, overdose awareness training, and general substance use education.

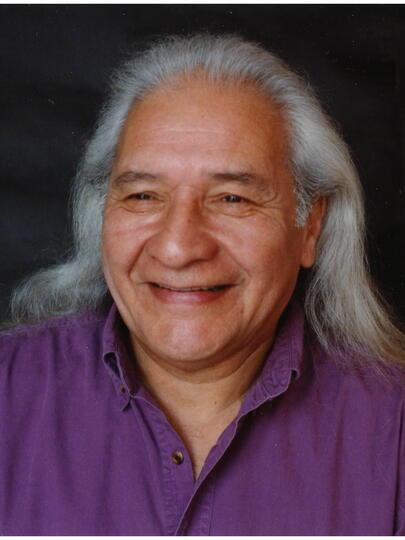

Doctoral student and HaRT team lead Lauren Airth explains the drug-checking process.

Established in late 2020, the HaRT program is unique because it’s the first time a local health authority has partnered with a university to offer drug checking with a spectrometer on campus. In addition, HaRT consists of an interdisciplinary student team from the School of Nursing’s doctoral, master’s, and bachelor-level programs, along with students studying international relations, electrical engineering, medicine, computer science, and social work. Together, the team works closely with the student recovery community and peers with lived experience to provide interventions that can prevent harm related to substance use.

HaRT’s work is especially important given the Province of British Columbia declared a public health emergency in April 2016 related to the toxic drug supply. Since then, B.C. has consistently reported the highest toxic drug death rates of any province in Canada, with six people dying on average every day in 2021. The number of drug toxicity deaths continues to climb year-over-year, further amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We know there’s an incredible need for this service not only with the student community but in the Okanagan in general. We had to do a lot of innovative thinking with our partners since we were the first university to offer this kind of drug checking on a regular basis — during a pandemic no less,” says Lauren Airth, a doctoral student from the School of Nursing who serves as UBCO’s team lead for HaRT. Airth’s thesis is examining the feasibility of HaRT’s drug-checking program model, and she’s played an integral part in the program’s evolution since 2019.

“Young adults in the Okanagan use significantly more substances than young adults in the rest of B.C. There’s lots of pressure for university students to have a persona of confidence, and it impacts their mental health. There are many layers to substance use but at the end of the day, it’s very much related to mental health. HaRT wants to reduce that stigma while also improving student access to various harm reduction supports.”

“People talk about mental health and substance use as if they’re independent of one another, but it’s all just mental health at the end of the day."

Airth first developed an interest in mental health after graduating from high school in 2008 — even though at the time, people didn’t speak widely about mental health issues. During her undergrad at UBCO, Airth chose to focus her studies and work on mental health and substance use, which ultimately landed her in the field “for the long run.” However, it wasn’t until she was hired as a specialist with UBCO Campus Health in the spring of 2019 that Airth started to better understand the multiple layers involved in substance use.

“People talk about mental health and substance use as if they’re independent of one another, but it’s all just mental health at the end of the day — and when people don’t understand how substance use is related, it contributes to the stigma.

“Every single person at UBCO either uses substances or knows someone who does. No matter who they are or where they’re located, substance use is a relevant thing.”

The toxic-drug emergency is further complicated by the rise of benzodiazepines, which are typically prescribed as a sedative to treat anxiety, difficulties sleeping, and seizures. But when combined with other types of depressants like fentanyl, benzodiazepines can significantly increase the risk of overdose. In fact, benzodiazepines were detected in as many as 51 per cent of drug samples tested in the B.C. interior in January 2022, a trend that has been on the rise since the start of the pandemic. Drug checking is crucially important because it can detect benzodiazepines, which can be found in illicit drugs and don’t respond to naloxone, a publicly available treatment that reverses an opioid overdose.

HaRT’s spectrometer, which is provided by Interior Health, detects any substances in a drug sample that has a concentration of five per cent or greater, including stimulants like cocaine or ecstasy and adulterants added to drugs. To ensure that fentanyl and benzodiazepines are not missed by the spectrometer, immunoassay strips are then used to test for these two substances. While the strips cannot provide a specific concentration like the spectrometer, they provide a yes/no for when these substances are present at concentrations less than five per cent.

“When we’re checking the sample, we’re able to get students involved in the process because we can show them what the machine finds as it’s detecting the different substances,” Airth explains. She adds that students typically bring drugs such as cocaine, MDMA, and ketamine for drug checking.

“The bigger picture is that there isn’t a safe, regulated drug supply in the community and people are rolling the dice on unregulated substances,” says Airth. “HaRT has given us an opportunity to educate students and staff, so hopefully they feel more comfortable, connected, and supported. We want to open up important conversations about health and wellbeing, which can then help people decide how they’ll use their substances.”

Both Airth and Van De Mosselaer want UBC community members to know that it’s ok to get their drugs checked without fear of academic repercussions. “It’s a scary thing for students, so we’re working to facilitate these opportunities to sit down with them and have an open dialogue that reduces stigma,” says Van de Mosselaer.

Starting the conversation around drug checking

Partnerships have been key to the program, adds Airth. While oversight for the program lies with UBCO Campus Health, Interior Health, and the BC Centre for Substance Use, other partners contribute to the program in various ways, including Students’ Union UBC Okanagan, Campus Operations and Risk Management, Living Positive Resource Centre, South Okanagan Women in Need Society, KANDU (Knowledging All Nations and Developing Unity), and people with lived experience.

In addition to offering free, confidential drug checking on campus twice a week, HaRT also operates in the community, with locations in Vernon, Kelowna, and Penticton. By the end of July 2021, HaRT had seven locations and 15 drop-off sites in the Okanagan where individuals — associated with UBCO or not — can access low-barrier drug checking and harm reduction services.

"Drug toxicity is the leading cause of death for young people in B.C., and it’s only getting worse. We have to let people know there are options available.”

“There are so many people involved in this program, from volunteers and students to numerous community partners and people with lived experience. It’s very cool to see such an interdisciplinary team coming together to support people through this program in a way that’s meaningful to them,” says Airth.

Interior Health Medical Health Officer Dr. Karin Goodison adds: “When people access drug checking they’re able to talk openly about drug use without judgement, and receive information about what’s in their drugs so they can reduce risk. Drug checking technicians require a unique skill set. They understand the science and can translate it into meaningful harm reduction information, while creating an atmosphere where people who are often stigmatized and penalized for using drugs feel safe. We’re fortunate to have Lauren and her team providing this life-saving service.”

Airth says that UBCO was well-poised to start the conversation on drug checking in the Okanagan. “Being in a smaller community like UBCO has benefitted us because there aren’t as many resources available, so we can be part of the team to develop those resources. We’ve been able to bring together students across numerous programs and faculties to partner on this project, and I don’t know if you’d see such interdisciplinary relationships on a larger campus.

“We have so many different people with different skill sets who have come together to do what they do best, which is trying to help others open the conversation around drug use. Drug toxicity is the leading cause of death for young people in B.C., and it’s only getting worse. We have to let people know there are options available.”