Turning screw-ups into successes

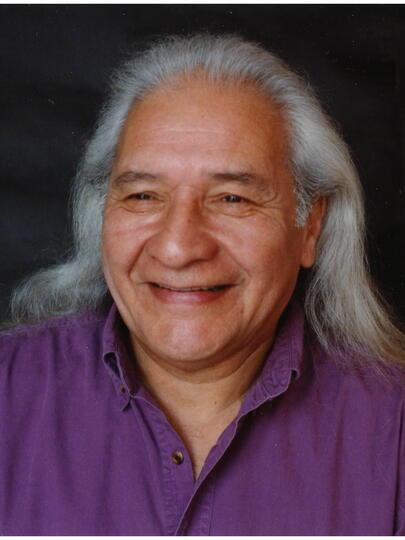

A UBC grad, who became a startup CEO in Africa, discovers how to draw strength from reassessing failures.

The next time you have to make a financial transaction, consider the following.

What if, in order to send money to someone, you had to undertake a 17-hour journey by car? And what if your only alternative was hiring someone to take the cash for you, such as a bus or truck driver — who might steal the money? Or what if, as a company owner, you could only make payments by transporting truckloads of cash with armed guards on high-risk trips to isolated destinations?

Although there’s since been a sea change, these were the only options available to the majority of people in Africa a mere decade ago.

A few years after graduating from university, UBC mechanical engineering grad Mike Quinn (BASc’03) sought to make the lives of such citizens easier with technological convenience. He and his cofounders launched a company providing easy access to money transfers in Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique.

In its prime, the company had a network of 3,000 micro-entrepreneurs who processed tens of millions of dollars in monthly transactions. Moreover, many female agents became the breadwinners in their families who supported others in completing their education. Quinn was even named a Schwab Foundation Social Entrepreneur of the Year in 2018 for his work.

All these achievements sound impressive — and they are.

Over a decade, the company would raise over $35 million in venture investment and boast over $2.5 billion in transactions.

So how could the company eventually wind up seemingly locked in a death spiral, prompting Quinn to reluctantly step down in 2019 and feel traumatized by the whole experience? The above successes tell only part of the tale. In his new self-published book Failing to Win: Hard-Earned Lessons from a Purpose-Driven Startup, Quinn shares the full story of what happened to help others learn from what he discovered about the value of “embracing failure.”

What set Quinn (who originally hails from Calgary, Alberta) upon a path towards entrepreneurship can be traced back to his undergrad years at UBC in Vancouver. As a student, he discovered a newly formed chapter of Engineers Without Borders Canada (EWB) in 2003. The idea of engineering students tackling global poverty ignited a spark within him — and changed his life. He was off to Ghana that year as an EWB volunteer, where he survived on $300 a month while working on a project to support small rural enterprises. Then in 2005, he led an EWB effort in Zambia to encourage smallholder farmers to switch from climate-inappropriate maize crops to drought-resistant sorghum.

Although that project floundered, it was in the capital of Zambia, Lusaka, that Quinn would later become a cofounder and CEO of a fintech (financial technology) social enterprise. Launched in 2009, Zoona (pronounced zo-oh-na in the Nyanja language or the approximation zoh-na) would help customers, without bank accounts, conduct money transfers. Agents in kiosks would earn commission for processing money transfers and cash payments using mobile phones with internet access (before smart phones). It was a hit. Over a decade, the company would raise over $35 million in venture investment and boast over $2.5 billion in transactions.

But Quinn’s book makes it clear that his time as Zoona’s CEO wasn’t smooth sailing — it was an unpredictable ride filled with ongoing struggles and crises, spanning highs and lows as well as periods of great uncertainty. He and his cofounders faced an accumulating number of internal conflicts, customer problems, staff layoffs, a currency crash, a cholera outbreak, and an array of other issues.

As investor challenges and aggressive competition snowballed over time, things would culminate in Quinn having to make the most painful call of all: resigning as CEO.

But writing about what happened, he explains in a Zoom interview from London, England, offered him a clearer view of the bigger picture. Quinn began writing about his experiences after quitting as a way to process everything that went down. As he wrote, he began to realize the value that lies in reassessing failure.

The silver lining in screwing up

What “clicked” for him in the writing and editing process was discovering “how failing is not a bad thing.” Accordingly, Quinn concludes each of his chapters with lessons learned from what went awry. These include simple takeaways, like holding meals before board meetings to help them run more effectively, and advice on more complex issues, such as resolving internal differences (“When I look back, I shudder at how much time and emotional strain it took for our founding team to come together and work as a team, at great expense to our business,” he writes).

While his experiences may be based in the financial sector, what Quinn has learned about owning up to his mistakes may be applicable to any number of other fields.

“I really wanted to demystify failure and make it more normal because I do think it’s a totally normal process and it’s a very healthy process,” he says.

It’s also a very relatable one. In recent years, various events around the world have arisen involving people sharing their professional disasters, including ones where fellow entrepreneurs hugged Quinn after he presented his story. Every time he told a business person or entrepreneur about what happened, they would say, “Ohhh, I had a similar experience.” Yet despite how commonly failure is experienced, Quinn felt that no one was discussing their screw-ups on social media like LinkedIn and he found that most entrepreneurship stories still focus on success.

Contrary to popular perception, revisiting failure and admitting mistakes doesn’t have to be an exercise in self-flagellation. Far from it.

“Writing helped me realize that, you know what, we were winning the whole time,” he says. It made him take stock of “how far we had come, how much I had personally grown, how much success we had achieved,” and how helpful “the process of failure” actually was. That led to his realization that he had a “failing, in order to win, story.” Consequently, he drew upon his crash-course experiences at Zoona (which, incidentally, managed to survive) to achieve success when he launched his second startup, Boost, which provides a commerce platform for retail entrepreneurs in Africa.

“I really wanted to demystify failure and make it more normal because I do think it’s a totally normal process and it’s a very healthy process.”

Something integral to his recovery from the aftermath of his Zoona resignation was realizing the difference between “you failed” and “you’re a failure.” This essential distinction, which Quinn says he struggled to recognize, separated criticism of his decisions from who he is as a person.

“If you can learn to hear the former and block out the latter, you allow yourself an opportunity for growth,” he writes in his book.

That’s not always easy to do, especially for entrepreneurs who can be engulfed in all-consuming endeavours that can make self-neglect almost inevitable.

Investing in self-care

While the majority of Quinn’s book focuses on business and financial aspects, he hints at the emotional, mental, and physical strain upon all involved, including anxiety, stress, self-doubt, burnout, and possible depression. In one extreme case, the cofounders had to stage an intervention to stop one of their colleagues from excessively overworking himself.

When asked what advice he would give entrepreneurs about self-care, Quinn recommends focusing on managing your energy rather than your time.

He emphasizes the importance of building habits and routines to “recharge your batteries.” For instance, Quinn meditates every morning, does yoga once a week, runs twice a week, and spends time with his family — he says he notices that he becomes worn down when he stops doing these things.

“You have to take care of yourself. You won’t make good decisions if you’re burnt out or if you’re drained all the time,” he says.

When to quit

What may be hard for some to admit, Quinn acknowledges, is that not everyone is suited for the demanding nature of entrepreneurship.

“You are trying to take like sometimes a 20- or 30-year career and condense it down into a very intense, few-year experience in a startup because you’re scaling and experiencing so much at the same time, and you don’t necessarily have that support structure around,” he explains.

It can be hard to distinguish between soldiering on in the face of insurmountable problems and recognizing when it’s time to change course or even call it quits.

“To avoid feeling like a failure, you’re pushed to keep going on and on and on, but that may not be the right decision,” he says.

Quinn admits that, in some business aspects, there aren’t always clear-cut answers. Yet that ambiguity also underlines his emphasis on learning from trial and error to gain something that can’t always be taught: expertise from experience.

In fact, in spite of all that he has undergone, Quinn still firmly believes in the power of being an entrepreneur. In addition, he says he gets “a lot of joy” from helping other founders, and his book exemplifies that by sharing his knowledge with them. From those struggling to find a new job to new leaders uncertain of what direction to take their team in, Quinn’s advice suggests that finding success may lie in viewing past failures as sources of potential strengths and breakthroughs. It may simply be a matter of perspective.