Change of Plans

Community planning holds tremendous consequences for any urban or rural environment, but perhaps especially for Indigenous communities. Taken together, First Nations face greater deficits of infrastructure, community services, and economic capacity than the rest of Canada. At the same time, they are stewards of treasured cultural, heritage, and natural resources that need protection and sound management. The stakes of planning, in other words, have never been higher.

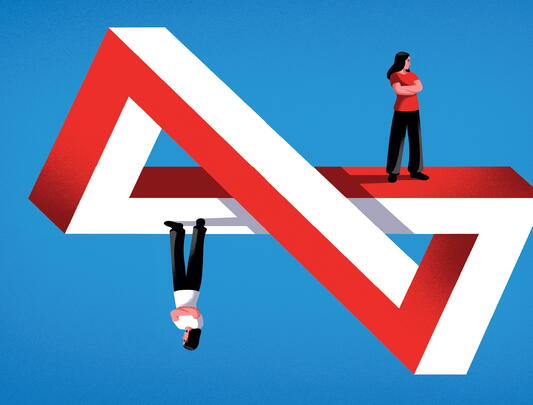

Shame, then, that standard community plans have a history of not working in Canada’s First Nations. Consultant driven, these plans are most attuned to the siloed mandates of government agencies that separately regulate infrastructure, housing, industry, health, and so on. They are less effective as tools to express and enact people’s own vision of community.

“There’s lots of cynicism about plans that get made and then just sit on the shelf,” says Iain Marjoribanks, who will graduate from UBC’s master’s program in Indigenous Community Planning (ICP) this fall. Why bother with a planning process that doesn’t reflect the people—all the people—it’s supposed to serve? Fuelling the skepticism are wariness and frustration around drawn-out treaty processes; unaddressed water, housing, and health crises on reserve; and the ongoing conservation vs development debate that haunts resource negotiations with government and industry.

Based out of UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning (SCARP), the ICP program adopts a different approach, one spearheaded by First Nations in BC and formally backed by the federal government beginning in 2004. The primary goal of this Comprehensive Community Planning is to place planning impetus and control where they belong: in the hands of Indigenous communities, which possess centuries of planning expertise in their own right.

The best Comprehensive Community Plans (CCPs) express a First Nation’s holistic vision for generational community growth and harmony. They rely on traditional ecological knowledge about how to utilize and protect the land. And they are valuable tools to assist in talks and negotiations with industry, developers, and governments.

With so much riding on the success of CCPs, how are the students of the ICP master’s concentration helping to usher in this planning revolution?

Marjoribanks and fellow class member Rachel Wuttunee used a jar full of jelly beans. They prepared a short survey for Homalco First Nation members. If you filled out a survey, you earned a guess at the number of jelly beans and a chance to win them. Kids, of course, flocked‚ but “they dragged their grandmas over, too.” It was a startlingly simple strategy to involve the community in the planning process.

This might seem like child’s play, but it prioritizes what standard planning models often overlook: the aspirations of community members. By accepting community-led planning as common sense, ICP students and partners want to decolonize the way planners, industry, government—and the university—engage with Canada’s First Nations.

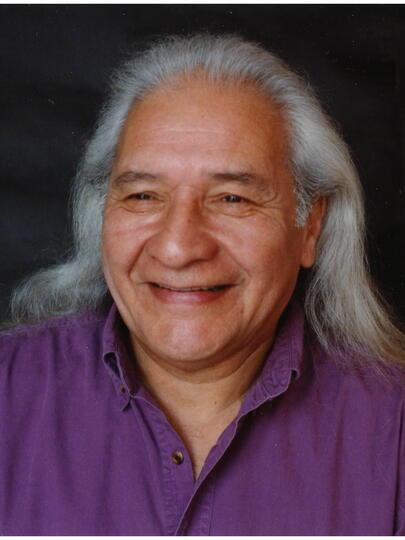

Professor Leonie Sandercock and Leona Sparrow, Musqueam Liaison to UBC and member of the Musqueam Intergovernmental Affairs Group, are known affectionately by students as the “mothers of ICP.” Since 2012, they have been building what school director Heather Campbell calls “a precious gem in the world of SCARP.” From the get-go, they recognized that a new approach to planning required a new approach to teaching planning. “This needed to be something very different than traditional university learning,” says Sandercock. Instead, ICP would embrace “the importance of community-based and land-based learning.”

The primary goal of this Comprehensive Community Planning is to place planning impetus and control where they belong: in the hands of Indigenous communities, which possess centuries of planning expertise in their own right.

The result was a partnership between SCARP and the Musqueam Indian Band, on whose unceded territory UBC sits. The band’s own planning experience is foundational to ICP’s teaching model. Their UNESCO-award-winning CCP was “developed by and for community members based on their own vision and cultural teachings,” says Sparrow. Musqueam expertise has paved the way for more than 15 BC First Nations, from the Skidegate Band Council on Haida Gwaii to the Tobacco Plains Indian Band in East Kootenay, to become ICP allies and practicum hosts.

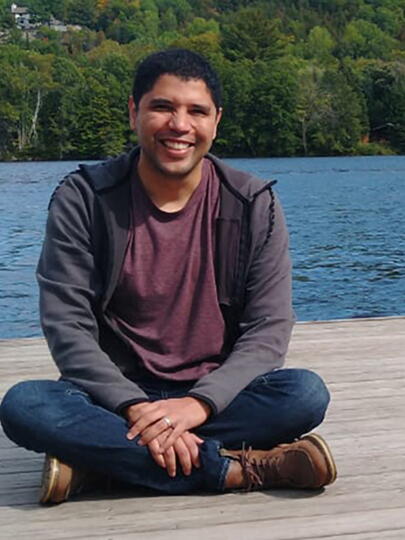

For the second-year practicum, pairs of students spend 400 hours on reserve, supporting a host First Nation in its own CCP process. The opportunity to work so closely with, and within, an Indigenous community is a first in the field of planning education. It is hands-on training unavailable in any other Canadian graduate program. While student Cody Kenny had worked as a recreation programmer for Aboriginal youth, his practicum with Stellat’en First Nation “was an awesome experience. … It was the first time I ever led a community engagement process … where you’re trying to acquire data. It was a lot more responsibility than other positions.”

Practicum work more or less follows a seasonal cycle: creating community awareness in the fall, engaging with community and collecting data in the winter, and reporting back in the spring. But this schematic obscures the huge variety of activities involved. Trust-building alone can involve everything from working with a local planning champion and advisory committee, to hosting youth art workshops, to social media outreach, to conducting door-to-door interviews, to coordinating Christmas dinner.

Most important, every community has different needs, and ICP planners take their cues from the community, even—or especially—when it changes the script. When Halalt First Nation suffered the unexpected deaths of multiple community members during the winter of Desiree Givens’ and Laura Hillis’ practicum, for instance, the planning process grew to encompass more than the development of a CCP. It became a way to lift community spirits.

ICP students are making good on the program’s trailblazing potential. The annual class is restricted to 10 students, at least half of whom identify as Indigenous, though they hail from across Canada and beyond. You’d be hard-pressed to find a more diverse crew. Nonetheless, Sandercock remarks, “some kind of transformative experience … has made them feel committed to addressing this foundational injustice” of Canada’s “dispossession of Indigenous peoples and … the attempt to annihilate them and their culture.”

Trust-building alone can involve everything from working with a local planning champion and advisory committee, to hosting youth art workshops, to social media outreach, to conducting door-to-door interviews, to coordinating Christmas dinner.

Robbie Knott’s transformation came when he was a human kinetics undergrad searching for an internship: “There was not one affiliation with any Indigenous organization. I was encouraged to just find what I could, and I would not settle for that.” He organized his own work term with the Kelowna Friendship Centre. “It was only about a four-month experience, but afterwards I went home, and I knew … this was my calling. This was my vocation—[though I was] unsure of what that meant.”

Talk of epiphanies is faint on university campuses compared to the noise around career tracks and projected salaries. But though virtually all ICP alumni are employed in the field, many are activists first and foremost.

Wuttunee has been an activist since childhood. “As a front-line worker and an advocate [for Indigenous youth at risk], I saw how systems were put in place for them to fail.” Her practicum with ICP was simply a continuation of her life’s work. “What was new for me was doing planning at that level … , and that process. But going into a First Nation and facilitating? I’ve been doing that since I was 19, since 2006.”

When the focus is on inclusivity and Indigenous self-determination, the planner becomes not a dispenser of “expert” guidance but a listener who respects centuries-old Indigenous knowledge, not least in the fields of land use and sustainability. The resulting plan might be a one-page statement of shared values or a 150-page document containing detailed data analysis and action plans around specific community goals. But CCPs are explicitly informed by Indigenous land-based knowledge in a way standard “cookie-cutter” plans (to borrow Sandercock's phrase) are not.

The difference is apparent in the Skidegate Band Council’s CCP, a process ICP students supported over the course of four different practicum terms. The plan begins with a statement of Haida Guiding Laws in their native language to show how they continue to inform the community’s priorities. It also likens the planning process to the five-phase salmon cycle so integral to traditional Haida ways of life: “Like the salmon cycle that Haida have come to rely on, Skidegate’s planning cycle grows and adapts through each cycle” (Skidegate Comprehensive Community Plan 2017, 15).

Many CCPs also project a different vision of the function of planning, which is less about reaping immediate benefits and more about planting healthy seeds that will grow into the distant future. Wuttunee cites the Cree practice of looking seven generations ahead: planning “for 200 years instead of making a one-to-five-year strategic plan.”

It’s a perspective that might otherwise be missing from university curricula. As Wuttunee observes, ICP “is going to become more powerful the more Aboriginal students come into that program and bring their knowledge and their gifts into it.” Their influence, in turn, will hold the university accountable to its strategic commitment to “partner with Indigenous communities on and off campus to address the legacy of colonialism and to co-develop knowledge and relationships.” (Shaping UBC’s Next Century, 13).

Many CCPs also project a different vision of the function of planning, which is less about reaping immediate benefits and more about planting healthy seeds that will grow into the distant future.

“I keep throwing around these words like ‘transformational,’ but it truly was,” says Knott, who lived on the corner of Main and Hastings and volunteered at the Carnegie Community Centre while completing his master’s. “It was almost as though my world view changed from the two years I was in the program. It was a metamorphosis, and it was just complemented by all these other things, and the encouragement you get in the program to expand your ways of knowing by interacting with these communities.”

The future of ICP is uncertain. Securing ongoing core funding, according to Sparrow and Sandercock, is still the program’s number-one challenge. And yet the CCP ethos, born in BC, is just beginning to gain traction nationally as the federal government spreads awareness to First Nations in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and the Atlantic provinces – and ICP students have the potential to decolonize the planning process in UBC classrooms, in industry, in Canadian planning offices, and on reserve.

What that will look like remains to be seen, which is just fine. “ICP is holding space for that Aboriginal way of knowing, and that is a sense of belonging, and that’s what First Nation communities need,” says Wuttunee. “And we need our non-Indigenous allies who know this Indigenous way of knowing. … ICP holds the space for that to emerge.”