Democracy across the Americas is in crisis

Political crises are rocking several nations of the Americas. From El Salvador and Venezuela to Bolivia, Argentina, and the United States, political crises are posing serious challenges to democratic institutions.

In some ways, democracy is simple. There are elections, and there are winners and losers. Winners get to govern for a period of time, and the losers have to accept their loss and prepare to fight again another day. The voters see that, for better or worse, a government has been elected by a majority and it has the legitimacy to carry out its program.

These days elections are not so simple. Sometimes governments try to control election authorities. Often losers simply don’t accept the outcome. Such electoral denialism is increasingly common, and this erodes the trust of the public. What many voters do know is that governments are either not listening to their problems, or are helpless to solve them.

This is the situation in many of the countries in the Andean region, according to a report I recently prepared for the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) in collaboration with my doctoral student Paolo Sosa-Villagarcia. We took a deep dive into the politics of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and what we found was disturbing.

To preserve democracy, democratic leaders and citizens will have to get back to the basics: free and fair elections, the rule of law, and a vibrant civic culture.

Democracy under threat

Venezuela’s government has become more dictatorial under President Nicolás Maduro. This year, the country held elections which have been among the most fraudulent ever seen in the region.

Maduro’s government refused to accept the victory of the opposition, and instead proclaimed the president re-elected. The government then proceeded to persecute the opposition leaders.

Peru is governed by an alliance of two unpopular forces: a corrupt congress and an alternate president who took office after the elected president tried to shut congress in a self-coup.

The opposition in congress never accepted the election outcome and repeatedly sought to remove former president Pedro Castillo.

Once they removed Castillo and found a pliable ally in the vice-president and current president Dina Boluarte they refused to hold elections and are using the remainder of their term in office to extend their control over the courts and the electoral authorities.

Bolivia is in crisis as former president Evo Morales opposes his own party in government, even accusing it of an assassination attempt. The current government of President Luis Arce was elected after Morales was removed from office in 2019 amid dubious elections.

The controversy around the 2019 Bolivian election has not been definitively resolved, but Morales’ meddling in the courts and election authorities made many Bolivians suspicious about his seeming desire to remain indefinitely in office.

The rise of Donald Trump in the United States casts a long shadow across the Americas. His ascendancy to the US presidency has emboldened reactionary forces throughout the region. Leaders in countries like Argentina and El Salvador champion Trumpian solutions to socioeconomic problems, threatening to reverse decades of work to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms.

The picture is slightly brighter in Ecuador and Colombia, but only slightly. Elections were held in Ecuador after President Guillermo Lasso, facing mounting opposition and charges of corruption, opted to end his term and that of congress as well (this is called death by cross-fire, or “muerte cruzada”). At least this was a constitutional solution.

Nonetheless, Ecuador’s recently-elected government of President Daniel Noboa is besieged by criminal gangs that have unleashed an astonishing level of violence.

Colombia’s president Gustavo Petro also enjoys undisputed electoral legitimacy. However, he is confronting massive governance challenges as he struggles to get his political agenda through the legislature where he has few allies and in the face of an electoral finance investigations which he characterizes as a coup effort.

What our report says

In our report, we suggested several diagnostic lessons to be taken from these cases. Perhaps one of the ironies of the report is that the diagnosis and prescriptions we make could apply to several established democracies, especially the United States.

Our diagnosis is as follows: Electoral authorities are besieged. There are threats to their autonomy from a wide range of forces. Yet they are vital to the capacity of states to hold free and fair elections.

This leads to the second diagnosis: The autonomy of election authorities is part of the larger problem of the weakness of the rule of law. Latin American states often lack the capacity to resist capture by powerful actors. Bureaucratic organizations are weak and underfunded, compliance with the law is low, impunity is rampant, and, in some cases, like Ecuador, violence is out of control.

This brings us to a third diagnostic: corruption of politics. Sometimes the problem comes from within, as when leaders politicize the courts and election authorities in the hope of perpetuating themselves in power.

Other times, the powerful actors come from outside the state — they may be criminal mafias, black market entrepreneurs, powerful oligarchs, or even social movements seeking to overturn democratic outcomes, as in the case of protests orchestrated to remove Peru’s Pedro Castillo.

Each of these problems has a solution or prescription. The first is to reinforce the autonomy and guarantee the impartiality of election authorities.

The second is to strengthen the rule of law by respecting judicial independence and the separation of powers.

Finally, governments need to promote and encourage a civic culture through dialogue, education, and opportunities for participation in political decision-making.

In principle, these efforts are mutually reinforcing. A more civic culture is likely to develop when people trust institutions, and people trust institutions when they actually deliver the goods. That is the virtuous cycle that fosters democratization.

Sadly, in recent years, it has been replaced by a vicious cycle of bad behaviour, institutional decay, and a loss of public trust. The election of Trump in the US is going to make it harder than ever to shift from the vicious to the virtuous solution.![]()

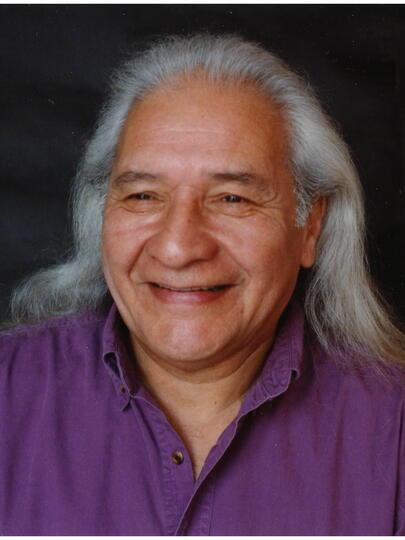

Max Cameron (BA'84) is a Professor of Political Science at the University of British Columbia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()